Latok 1

BESIDES the 8000-meter giants, the Karakoram contains countless attractive smaller peaks. Though much lower, they often make up in difficulty what they lack in altitude. On the northern edge of the Biafo Glacier rise the Ogre (Baintha Brakk) and the Latok peaks.

BESIDES the 8000-meter giants, the Karakoram contains countless attractive smaller peaks. Though much lower, they often make up in difficulty what they lack in altitude. On the northern edge of the Biafo Glacier rise the Ogre (Baintha Brakk) and the Latok peaks.

Our expedition attempted Latok I (23,440 feet), the highest unclimbed peak in the group and only some 500 feet lower than the Ogre. There had been three previous expeditions to Latok I, two Japanese and one Italian. All three had gone to the southern side and all had been repulsed low on the mountain by avalanche danger.

There is no easy way up the precipitous, ice-encrusted walls of this imposing mountain. The easiest route would present the technical challenge of the hardest peaks in North America. We planned a route from the north, a fine direct ridge that sweeps 8000 feet up rock and ice. The climbing would be difficult but it appeared to be perhaps the only route free of objective danger. The weather would be variable and the mountain was high and remote. We intended to climb alpine-style.

George Lowe, his cousin Jeff Lowe, Jim Donini and I were the climbing team. We were accompanied to Base Camp by two doctors, Dr. George Lowe Sr. and Dr. Ralph Richards.

After the Pakistani government gave us final permission in early March, preparations began in earnest. All our equipment and most of our food was brought from the United States, but we bought staple items such as sugar, flour, tea, rice and powdered milk overseas. We arrived in Rawalpindi on June 10 but had to wait for six days for lost baggage, customs clearance, bureaucratic formalities and the purchase of additional supplies. We had a five-day wait after our flight to Skardu until our baggage finally arrived. Such delays may seem long, but they were really minimal for Pakistan.

We traveled the first 50 miles from Skardu by jeep. Then began the long, hot walk to Base Camp. The first four nights of the approach were spent in villages, nestled in green oases along the Braldu River gorge in this harsh, precipitous desert. It was so hot during the day that we started at three A.M. to be able to sleep away the torrid afternoon hours. Beyond Askole we left human habitation and ascended the Panmah and Choktoi glaciers.

We took three days in Base Camp at 15,500 feet to rest and sort out food and gear for the climb. Steep, narrow and icy, the north ridge of Latok I dominated the skyline, its base a mile and a half away. We gave ourselves only a 50-50 chance of success. Seventeen days of food was largely freeze-dried with generous additions of nuts, cheese, dried meat and fruit, peanut butter and candy. When this was added to full winter clothing, sleeping gear, tents, stoves, fuel, eight ropes, 60 rock pitons and 30 ice screws, it amounted to 350 pounds.

We took three days in Base Camp at 15,500 feet to rest and sort out food and gear for the climb. Steep, narrow and icy, the north ridge of Latok I dominated the skyline, its base a mile and a half away. We gave ourselves only a 50-50 chance of success. Seventeen days of food was largely freeze-dried with generous additions of nuts, cheese, dried meat and fruit, peanut butter and candy. When this was added to full winter clothing, sleeping gear, tents, stoves, fuel, eight ropes, 60 rock pitons and 30 ice screws, it amounted to 350 pounds.

Each day one pair led, leaving ropes fixed behind. The other two ascended with Jümars, carrying the loads. For the first few days this pair had to make several trips up the ropes before pulling them up, but finally we ate enough to lighten the loads. The next day we switched. It was scarier to lead, but easier than jümaring with a 60-pound pack.

Although the climbing on the first day was not too difficult, we made only 800 feet. We hadn’t yet figured out how to deal with all the weight and the heat was merciless. On the second day we got to 17,500 feet with the same problems of heat and weight and more difficult climbing. Since the altitude was beginning to bother and because we were tired, we rested on the third day. A six-day storm broke on the fourth. Though we managed to climb some during this period, we were still immobilized at 18,500 feet for three days, surviving on half-rations and hope.

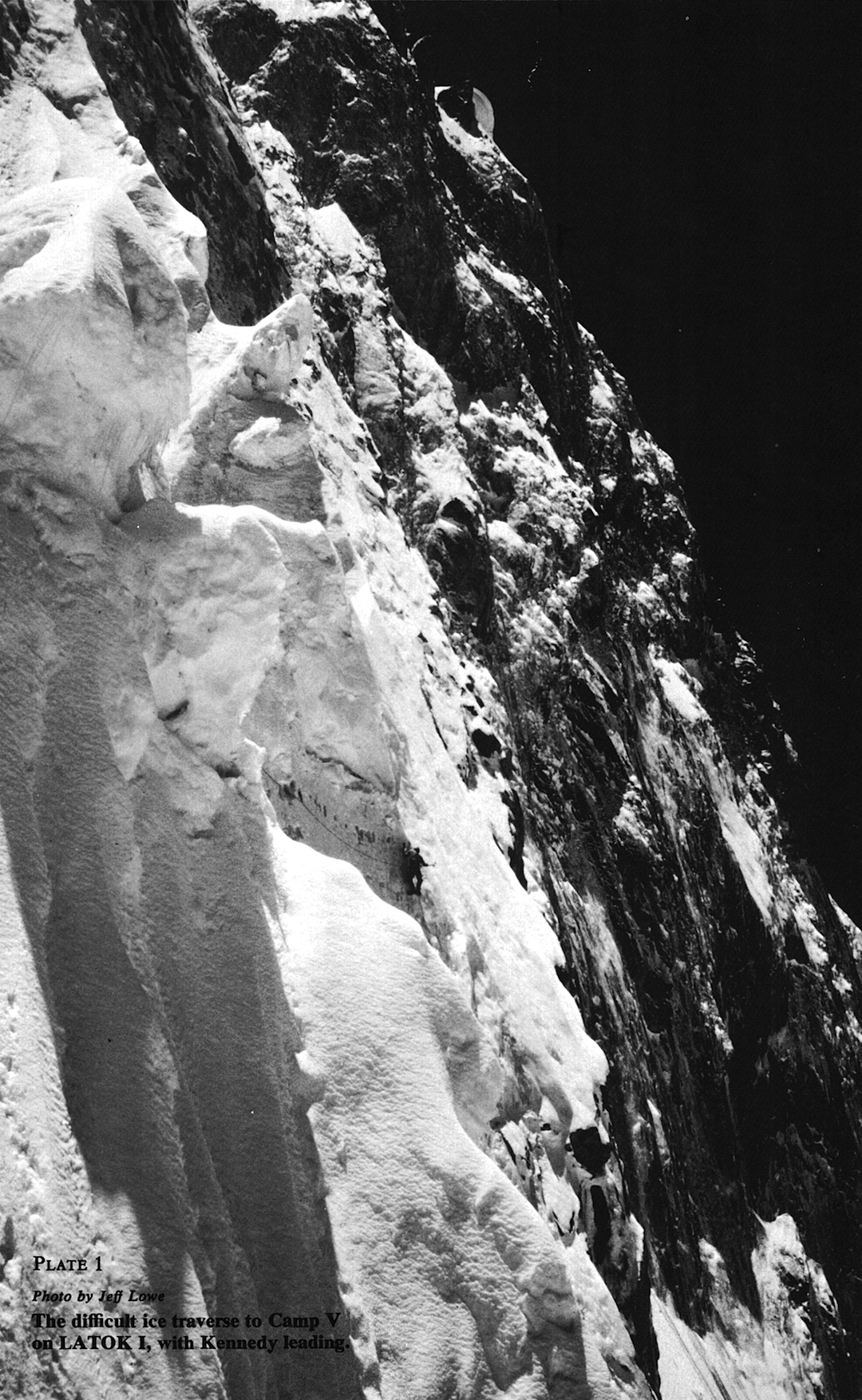

When the storm finally did end, we had an extended period of perfect weather. The climbing remained difficult, though never desperate. Yet it just never let up. Each step required caution, and we stayed roped even when sleeping.

The higher we got, the worse the campsites became. We slept three nights out in the open above 21,000 feet, sitting on tiny ledges hacked out of the ice. The altitude took its toll. We always needed two hours each morning to get started, and even minor tasks took a major effort. We had to drink endless cups of hot tea to keep some semblance of hydration and that took hours of melting snow and boiling water. Carrying loads was agonizing until we found the proper pace: one step, one breath, with a pause every ten paces for a proper rest.

It wasn’t all grim. The scenery was gorgeous. We had the exhilaration of 7000 feet of exposure down to the glacier below. We had been on the climb so long that it seemed as if it was the only thing we had ever known. Memories faded into the distant past. Each day was routine: get up, put on a brew, eat, boots on, dress against the cold, pack the gear, climb, haul loads, hack out a platform, eat, sleep—the details were all the same, the days were alike, blurred into a simple ritual of the climb.

On our 19th day we took what little food remained—about three days’ worth—and a minimum of equipment and made a push for the summit. At 22,700 feet the snow was finally deep enough to dig a snow cave. We fixed two ropes above the cave over the final difficulties to reach easy snow-and-ice slopes leading to the summit ridge. It was still some 700 feet to the top, but the going was much easier. We huddled anxiously together in the snow cave as another massive front moved in from the northeast.

The 20th day crept slowly by. A foot of new snow had fallen overnight, and we put off our summit attempt in hopes of better weather. That night it snowed another foot, but food was low and so we tried for the top anyhow. We turned back perhaps 300 feet from the summit ridge and 500 feet from the top in the face of wind, spindrift and cold. Now there was another complication. Jeff had been somewhat sick since we had arrived at the snow cave and the summit try had really put him under. He became very ill, so ill that we feared for his life. Almost out of food and fuel in the continuing storm, we knew that we would have to spend one, or perhaps two nights out in the open on the descent. Could Jeff survive it?

After five nights in the cave, we had no choice but to go down. We divided up Jeff’s gear. The storm continued unabated. Feet and hands froze, and nearly three feet of new snow slowed progress. Our prolonged stay at that altitude had weakened us. Even when we had all our clothing on, the cold cut right through. Frostbite was a constant threat and forced us into frequent halts to warm extremities.

After five nights in the cave, we had no choice but to go down. We divided up Jeff’s gear. The storm continued unabated. Feet and hands froze, and nearly three feet of new snow slowed progress. Our prolonged stay at that altitude had weakened us. Even when we had all our clothing on, the cold cut right through. Frostbite was a constant threat and forced us into frequent halts to warm extremities.

We descended 1500 feet in fourteen hours to the first of our miserable bivouacs. Jeff seemed somewhat better, but I had removed my sun glasses that day and was suffering from snow blindness.

The storm continued the next day. Although Jeff was better, he was still weak and nauseous. We had next to nothing to eat, but we knew that there was a day’s food at the midpoint of the route, 2000 feet lower. Mercifully, we made it. There was room to set up tents, and the night was almost comfortable.

The sun was out on the last day of the descent. The rappels were all straight down and not diagonal. Even our hunger could not dampen our spirits. We chatted happily about our good fortune of being there. Had the storm really been that bad? Could we have made it to the top? But what we really cared about was getting down, alive, and going home.

We got back to Base Camp at dark, twenty-six days after leaving. We ate until our bellies ached—and that they did all night. After a rest and packing day, we started walking out. It was a hard trip on swollen feet, but that is a whole other story.

Summary of Statistics:

Area: Biafo Karakoram.

Attempted Ascent: Latok I, 23,440 feet, via north ridge; high point about 22,950 feet, July, 1978.

Personnel: James Donini, Michael Kennedy, George Lowe, Jeff Lowe.