K2: The End of a 40-Year American Quest

"To our predecessors on K2, upon whose shoulders we climbed." Louis F. Reichardt

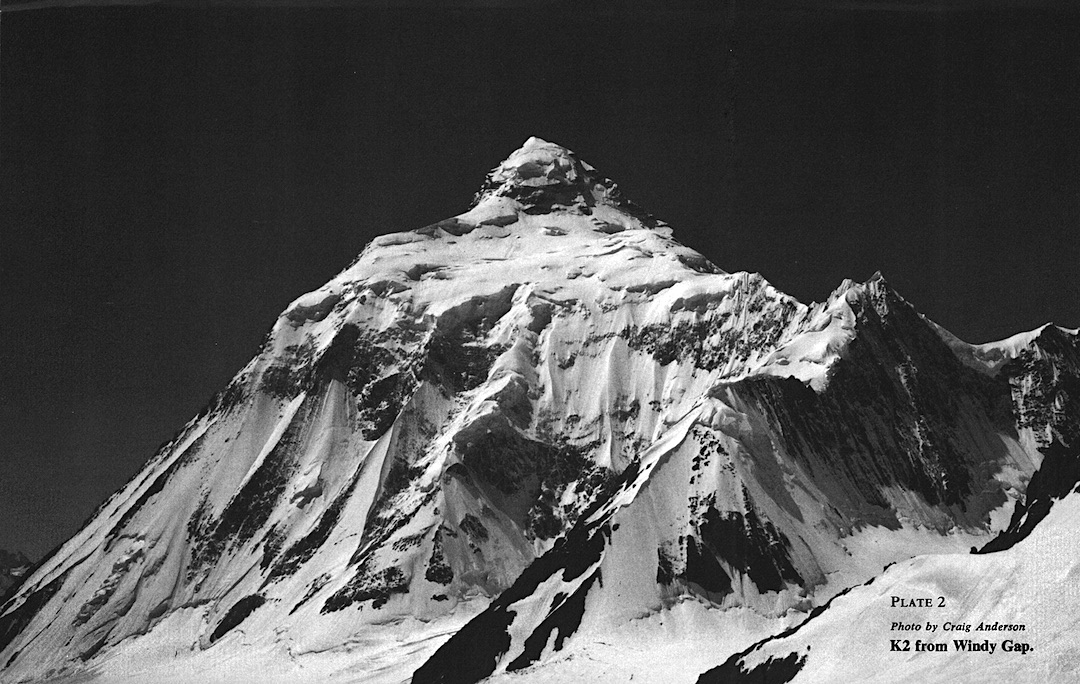

SITUATED in remote splendor at the upper end of the Baltoro Glacier, K2, second highest peak in the world, has always dominated the imaginations of mountaineers. Not visible from any inhabited place, it has presented intimidating profiles from all directions to both early explorers and modern alpinists. Sir Francis Young- husband described it in 1887 as “a sight … which fairly staggered me … a peak of appalling height … one of those sights which impress a man forever, and produce a lasting sense of the greatness and grandeur of nature’s works—which he can never lose or forget.”

If there is a single mountain that can symbolize for Americans the spiritual heights and tragic depths that are encountered in Asia’s mountains, it must be K2, because inspiring, but unsuccessful and often tragic American expeditions have dominated the history of this magnificent peak. Charles Houston’s 1938 expedition, using only 60 porters, made a thorough reconnaissance of possibilities on the mountain, proved there was a reasonable route to the summit by reaching nearly 26,000 feet on the Abruzzi Ridge, and might have gone further had they not followed the advice of an eminent contemporary: “Men cannot survive above 20,000 feet for more than a month,” and taken too little high-altitude food. Fritz Wiessner’s 1939 expedition went over 27,000 feet and Wiessner almost certainly had the summit within his reach. The “formality” was initially prevented by an unfortunate choice of route and then by a lost pair of crampons. A few days later, misunderstandings and foul weather forced an unplanned retreat and unimaginable tragedy. A climber was inadvertantly left behind at 25,000 feet, and three experienced Sherpas were lost with him in a futile rescue attempt. Finally, one admired the collective courage of the 1953 expedition, which had imminent success snatched away by bad weather and, in a dramatic change of fortune, was then forced to make an almost hopeless attempt to evacuate a sick comrade.

The quality of these efforts left no doubt that this mountain could bring forth the best from men—strength, team-work, and courage beyond the realm of the possible in our own experience. It was most disappointing that the 1960 and 1975 expeditions never reached the heights of their predecessors, so that 24 years after the 1954 Italian summmit climb, our own “Annapurna” still eluded us.

This was particularly galling to Jim Whittaker, whose 1975 expedition had been widely expected to be invincible, but had fallen victim to porter strikes and internal dissension amid circumstances very largely beyond his control. His attempts to gain permission for a second attempt in 1978 were initially refused. Only after a personal appeal to Prime Minister Bhutto from Senator Kennedy was permission granted, but this time with a handicap. Bonington’s British expedition would have the traditional time slot of May, June, and July; Whittaker would have to climb after July 15, when monsoon-generated storms often besiege the Karakoram. Undaunted by this obstacle and by Bonington’s late decision to pre-empt Whittaker’s chosen route, the west ridge, Jim and his wife, Dianne Roberts, redirected their efforts to the northeast ridge, which had almost been climbed in 1976 by a very strong Polish team, and proceeded almost single-handed to raise the funds and support for the new venture. “Put your name on top of K2,” read the flashy appeal. The climbers thought it was corny; few thought it was meant seriously; but for only $20 you did indeed have your name left on the summit. As a team, they chose eleven other climbers—a heterogeneous group mostly from the Northwest whose unifying attribute was prior experience at high altitudes. Whittaker and Chris Chandler had been to the summit of Everest; Cherie Bech had earned her position because she had made a two-person attempt on Dhaulagiri with her husband Terry that failed only 2000 feet short of the summit. All the climbers had had previous experience in the Himalaya. Their mountains ranged from Dhaulagiri and Nanda Devi to K2 and the Trangos. Dianne Roberts came as a photographer; Diana Jagerský as a cook; but interpreting their roles broadly, they were to climb as high as most of the “climbers.” Each one of us saw this as the most important expedition he or she was likely to have the opportunity to participate in, since K2 has held such a unique position in American climbing history.

This was particularly galling to Jim Whittaker, whose 1975 expedition had been widely expected to be invincible, but had fallen victim to porter strikes and internal dissension amid circumstances very largely beyond his control. His attempts to gain permission for a second attempt in 1978 were initially refused. Only after a personal appeal to Prime Minister Bhutto from Senator Kennedy was permission granted, but this time with a handicap. Bonington’s British expedition would have the traditional time slot of May, June, and July; Whittaker would have to climb after July 15, when monsoon-generated storms often besiege the Karakoram. Undaunted by this obstacle and by Bonington’s late decision to pre-empt Whittaker’s chosen route, the west ridge, Jim and his wife, Dianne Roberts, redirected their efforts to the northeast ridge, which had almost been climbed in 1976 by a very strong Polish team, and proceeded almost single-handed to raise the funds and support for the new venture. “Put your name on top of K2,” read the flashy appeal. The climbers thought it was corny; few thought it was meant seriously; but for only $20 you did indeed have your name left on the summit. As a team, they chose eleven other climbers—a heterogeneous group mostly from the Northwest whose unifying attribute was prior experience at high altitudes. Whittaker and Chris Chandler had been to the summit of Everest; Cherie Bech had earned her position because she had made a two-person attempt on Dhaulagiri with her husband Terry that failed only 2000 feet short of the summit. All the climbers had had previous experience in the Himalaya. Their mountains ranged from Dhaulagiri and Nanda Devi to K2 and the Trangos. Dianne Roberts came as a photographer; Diana Jagerský as a cook; but interpreting their roles broadly, they were to climb as high as most of the “climbers.” Each one of us saw this as the most important expedition he or she was likely to have the opportunity to participate in, since K2 has held such a unique position in American climbing history.

When the expedition members disembarked in Rawalpindi on June 15, it was with excitement, but also considerable trepidation. The 1975 expedition had spent 14 days there out of a total of 55 days needed to reach Base Camp. This time, the American community immediately took us under its wing, so at least the wait promised to be comfortable. The attitude of the Pakistani government, stung by criticisms from the 1975 team, seemed at first more ambivalent. “What lessons have you learned from your 1975 climb?” was the pointed query of one general. “We initially denied your application because it was too late. Then Senator Kennedy wrote the ex-Prime Minister asking if there was any way permission could be granted. … The ex-Prime Minister asked us to do this,” was the “greeting” of the head of the tourist office. In spite of these initial words, we could not have received better cooperation from the people we depended upon in Pakistan. In large part this was attributable to Whittaker’s experience. He hired excellent agents who moved the expedition’s freight to Skardu before the members left the United States. The Pakistani government also helped greatly, by giving us a superb liaison officer—Subadar Major Mohammed Saleem Khan— whose experience in the Karakoram stretched over 30 years; and by waiving many of the bureaucratic requirements that tend to immobilize expeditions in the capital. After two very hectic days spent in a frantic dash for porter equipment and supplies, we were able to locate our last required item—Pakistani flags for the summit—just as the store was cranking down its iron grille. The next morning, we were at the airport. To our surprise, the plane was flying. Still suffering from jet lag, we were dissecting the mountaineering opportunities on Nanga Parbat as that snow-draped giant drifted past our airplane windows, only four days after entering Pakistan.

Skardu provided our introduction to the stark beauty and diverse peoples of Central Asia in whose midst we were to live for the next three months. The majestic Indus, gliding through the sand dunes below the city, reminded me more of Egypt than any scenery I had encountered previously in the Indian or Nepalese Himalaya. Certainly, the high point of our brief stay there was a formal fête, hosted in our honor by the District Commissioner, at which dozens of Balti men performed a multitude of dances to the beat of drums and tambourines—some were solo, some were group; some were rhythmic, some frenetic and reminiscent of the Cossacks, scarfs and swords swirling in a dazzling display of color. We could not have had a more enjoyable introduction to the culture of the people who were to be our porters, and we took special care to ensure that the musicians accompanied us as porters to Base Camp.

In contrast, the low point of our stay was the arrival of Chris Bonington and Doug Scott with the news of Nick Estcourt’s tragic death on K2 in a windslab avalanche. This provided an uncomfortable reminder that there were aspects of “Russian Roulette,” even for the most experienced mountaineers, in this game that we had chosen to play. There were very few words that seemed adequate to express our shared sense of loss.

There was some talk of switching back to our original objective, the west ridge, since the British had abandoned it; but it did not really seem appropriate and little enthusiasm was generated for the idea. The freighted gear was opened and sorted. Personal equipment proved to have little resemblance to our sizes or lists, but adequate exchanges could usually be arranged. We hired 100 regular porters. The market in testimonial cards from the 1975 expedition proved to be very brisk. They passed down the line of would-be porters at roughly the same rate as the sahibs inspecting them. Those same cards reached the road-head, 60 miles from Skardu, before the expedition members, and there we hired 225 more wiry Baltis, each with a well-used chit signed by Whittaker: “This is one of 55 men who carried to Base Camp in 1975.”

The walk to Base Camp took only 13 days. As a newcomer, I had a vague sense of deprivation when I realized I would miss that exciting event which is part of every Karakoram expedition from the Duke of the Abruzzi to the present day—the porter strike. Our porters were good- natured and long-suffering. They even made the final stage to Base Camp without rations. Our worst problem was their insistence at the top of every pass that we dance with them in the broiling sun to disco music from a cassette recorder instead of collapsing in the shade. They clearly enjoyed our company, but I was afraid to think of the stories they would carry home of that bizarre group of sahibs, who expected to climb K2. On my first visit to the Karakoram, what impressed me most was the contrast in the terrain we were crossing. For the first few days, drab and dusty desert defiles alternated with verdant oases bursting with water, broad trees and ripening grain. Once on the Baltoro we only had to raise our eyes to forget the endless moraine and discomfort underfoot. The granite walls and alpine peaks had a magnificence and scale impossible to take in. On July 5, we paid off most of the porters at our 16,500-foot Base Camp set at the foot of K2, on the same historic site used in 1938, 1939, and 1953.

The walk to Base Camp took only 13 days. As a newcomer, I had a vague sense of deprivation when I realized I would miss that exciting event which is part of every Karakoram expedition from the Duke of the Abruzzi to the present day—the porter strike. Our porters were good- natured and long-suffering. They even made the final stage to Base Camp without rations. Our worst problem was their insistence at the top of every pass that we dance with them in the broiling sun to disco music from a cassette recorder instead of collapsing in the shade. They clearly enjoyed our company, but I was afraid to think of the stories they would carry home of that bizarre group of sahibs, who expected to climb K2. On my first visit to the Karakoram, what impressed me most was the contrast in the terrain we were crossing. For the first few days, drab and dusty desert defiles alternated with verdant oases bursting with water, broad trees and ripening grain. Once on the Baltoro we only had to raise our eyes to forget the endless moraine and discomfort underfoot. The granite walls and alpine peaks had a magnificence and scale impossible to take in. On July 5, we paid off most of the porters at our 16,500-foot Base Camp set at the foot of K2, on the same historic site used in 1938, 1939, and 1953.

One hundred thirty porters couldn’t be paid because we had underestimated their wages and had to wait for a mail runner to return with the money. This proved to be a fortunate miscalculation on our part since these hardy fellows worked while they waited and had by July 8 moved most of the expedition gear to Advanced Base Camp at 17,500 feet, roughly one-half mile beyond the Abruzzi Ridge on the Upper Godwin Austen Glacier. We developed no affection for this site, which was chosen as safe from ice avalanches, but proved all too susceptible to rockfall. The glacier beyond was flat, but pinned in a deep valley between K2 and Broad Peak. Avalanche clouds from K2’s upper slopes often obliterated our tracks, but a speeding sahib all too often found time for reflection at the bottom of a crevasse. One time, Ridgeway and Roskelley fell simultaneously into the same cavern as they were each trying to take over the lead from me. The next day Chandler and Cherie Bech fell in separately. It seemed only a matter of time until everyone had tested his self-rescue techniques.

Camp I, at the foot of the northeast ridge, was occupied on July 12. Chandler, Edmunds, Ridgeway and I were chosen to lead up the steep ice gullies to the ridge crest and from there to a Camp II site at 20,400 feet. On the first day we stayed together, admiring a lead of Chandler’s over steep mixed ground, while we ducked and cursed the whistling rocks dislodged by his rope. Everything on K2 at this height was so loose it wasn’t clear why it had not already joined the moraine on the glacier. The next day Chandler and Edmunds did some nice climbing to relocate this route into ice couloirs, while Ridgeway and I reached a good site for Camp II several hundred feet higher.

Wickwire and Whittaker occupied this camp on July 16, and the next day pushed the route 600 feet higher along a long snow ridge. Invited to join them for their second day, I was amazed at the efficiency with which “Big Jim” tromped out a trail through deep snow. “It is no mystery why he was first on Everest,” I realized. After eleven hours of alternating the lead, we reached a perfect spot for Camp III at 22,300 feet, a shallow depression protected from the wind by an overhanging ice block. When two days later Wickwire and I reached a saddle a few hundred yards further, we were rewarded with magnificent views of the 15,000-foot height of the north ridge of K2. Below it was the K2 Glacier, disappearing into the Shaksgam, that remote uninhabited part of Chinese Sinkiang, visited only by a handful of men since Younghus- band. The descent into China looked so much more inviting than the Baltoro that we were to discuss endlessly the probable reaction of a Chinese truck driver when he spotted the thumbs of two bearded Americans hitch-hiking; the first “climbing exchanges.” “The book will sell, but in what year will it be published?” we wondered.

Wickwire and Whittaker occupied this camp on July 16, and the next day pushed the route 600 feet higher along a long snow ridge. Invited to join them for their second day, I was amazed at the efficiency with which “Big Jim” tromped out a trail through deep snow. “It is no mystery why he was first on Everest,” I realized. After eleven hours of alternating the lead, we reached a perfect spot for Camp III at 22,300 feet, a shallow depression protected from the wind by an overhanging ice block. When two days later Wickwire and I reached a saddle a few hundred yards further, we were rewarded with magnificent views of the 15,000-foot height of the north ridge of K2. Below it was the K2 Glacier, disappearing into the Shaksgam, that remote uninhabited part of Chinese Sinkiang, visited only by a handful of men since Younghus- band. The descent into China looked so much more inviting than the Baltoro that we were to discuss endlessly the probable reaction of a Chinese truck driver when he spotted the thumbs of two bearded Americans hitch-hiking; the first “climbing exchanges.” “The book will sell, but in what year will it be published?” we wondered.

At this point, July 21, our steady ascent of the mountain was interrupted by an eight-day storm. For part of the time, everyone was forced down to the comfort of Camp I. It was useful to have all of us together, having gotten some feel of the scale of our objective. In a long evening session, we reached agreement on oxygen use—only at or above the highest camp—which was the basis for all our future logistics. Diana Jagerský was given a second hat—“logistics manager”—and thenceforth managed with great thoroughness to discover just how little was in our “50-pound” loads, the initial chink in the armor of male supremacy.

Camp III was occupied by Ridgeway, Roskelley, Wickwire, and Sumner on July 29 only after a 13-hour fight along the buried ropes above Camp II. Too tired to return, Wickwire and Sumner bivouacked in the tent without their sleeping gear. The ridge crest beyond Camp III had been climbed by the Poles, but we knew from their description that it would be one of the most challenging sections of the route. For almost a mile, this heavily corniced ridge crest runs horizontally, perched airily above the glaciers of China and Pakistan. The Poles had set out 4-man teams for ten straight days to do this section. Imagine our delight then when Ridgeway and Roskelley radioed down after only one day’s effort: “We’ve almost finished it.” It was difficult to believe so much steep terrain could be climbed and fixed with rope in such a short time. The next evening, after another full day’s labor, the mystery was clarified: “We still have a third of a mile to go.” They had learned that distances on that type of sinusoidal terrain can be extremely deceptive. Joining them on the third day, Sumner and Wickwire helped fix the route over most of that distance. On the fourth day, in spite of very severe weather, they completed their traverse—a magnificent performance.

Meanwhile, much of the hauling to the lower camps had been completed. Our four Hunza high-altitude porters—Honar Beg, Sanjer Jan, Gohar Shah, and Tsheran Shah—played crucial roles in supplying these camps, as did Diana Jagerský, who many of us felt was one of the strongest team members. “Diana Jagerský has this marvelous way of matching you step for step, whatever the pace, and afterwards insisting she is tired, leaving you a thin reed on which to maintain illusions of superior masculine strength.”

The storm that hit on the final day’s leading to Camp IV blocked progress for only three days. With the return of good weather on August 7, so much gear was transported across the traverse to Camp IV that the summit seemed close indeed, but we couldn’t help dwelling on the utter impossibility of evacuating anyone' seriously injured across this route, over which we pulled ourselves in a series of Tyrolean-type traverses with our full weight on the ropes draped down the 55° ice slopes between anchors. For several days, Wickwire, Roskelley, Ridgeway, and I had chattered idly among ourselves of the “logic” in climbing to the summit together. To our surprise, Whittaker proposed this plan publicly on August 9, feeilng the summit was imminent. However obvious it seemed to us, the silence from the rest of the team was ominous and foreboding.

On August 10, Edmunds and Anderson began the long push from Camp IV at 22,800 feet to Camp V at 25,200 feet. The clear skies were actually a handicap on the flat snowfields they had to cross. They progressed only a few hundred feet before their track threatened to become a tunnel. The next morning, Chandler and Cherie Bech joined them, but this time deteriorating weather forced a hasty retreat, again only a few hundred feet higher.

On August 10, Edmunds and Anderson began the long push from Camp IV at 22,800 feet to Camp V at 25,200 feet. The clear skies were actually a handicap on the flat snowfields they had to cross. They progressed only a few hundred feet before their track threatened to become a tunnel. The next morning, Chandler and Cherie Bech joined them, but this time deteriorating weather forced a hasty retreat, again only a few hundred feet higher.

The ensuing blizzard took a heavy toll on the expedition both physically and mentally. For the first time, climbers had failed to reach a higher campsite during a clear weather period. Delaying their evacuation of Camp IV for two days, the lead team found the ropes and drifts almost impossible to cope with. It took them ten hours to reach Camp III instead of the normal 90 minutes, and their toes and fingers were frostbitten. Arriving back in Camp I, I commented: “It is much colder. The mountain is rapidly entering into winter. Our Hunza porters provide little encouragement: ‘Winter snows start falling around August 25. It is a real possibility we will be stopped well short of the Poles.”

The return of clear skies on August 15 only heightened the frustration. “I started out, but the snow was waist-deep. It is dangerous,” radioed Anderson from Camp III, explaining why the lead team thought avalanche danger was too high to break a trail up or down the mountain. To those below the description hardly seemed credible. Soon the heat emanating from the radios threatened to burn the tents. Edmunds and Anderson did break out the route the next morning for several of us to join Chandler and Bech at Camp III for the “final push,” but the residue of slab avalanches had persuaded them not to open the route to Camp IV. “They should climb or let others go first,” was one opinion; the retort: “I’m not risking my life on those slopes so you can climb over my body to the summit.” Desperate to make up lost time in the face of impending winter, we adopted for the next morning one of the most foolish plans of the expedition. “We’ll have three waves of people—two to break to Camp IV early; two to follow and break out the existing ropes towards Camp V; and two more to add ropes beyond.” Unfortunately, the warm sun softened the footsteps of the first team so that the second and third teams were barely able to straggle into Camp IV at midday. “Cracking in the snowfields above discouraged further progress. That evening, August 17, the winds shifted from north to south, a harbinger of another monsoon-generated storm. It was 14 days since Camp IV had been reached and no real progress had been made since.

Leaving early the next morning, Ridgeway, Roskelley, and I crossed the avalanche slopes above Camp IV and reached the expedition s previous high point. Alternating curses at the waist-deep snow with silent prayers that it wouldn’t slide, Roskelley front-pointed up the underlying 45° ice for 300 feet to reach a final pinnacle. In intermittent snowfall, we traversed the vestigial remnants of the northeast ridge, now broad and shallow, as it merged into the face. Joined by Chandler, we alternated leads up a 1500-foot snow dome, reaching a Camp V site on top at three P.M. The northeast face of K2 glowered threateningly down on us, and snow flurries scudded across the slopes, but our mood couldn t have been brighter. “We did not expect to get nearly this far.”

“It’s incredible. It’s a heck of an accomplishment,” radioed Whit- taker.

“We’re really drained,” we replied, “but we got the ropes in and it is an easy walk to Camp VI.”

The next morning, the blizzard hit in earnest. With only 26 man- days food at Camp IV, retreat was imperative. Two days later I was in Camp I, “feeling like a yo-yo on my sixth trip down.” The summit seemed as remote as ever and the carry to Camp V an act of pointless élan: “Very little gear was carried, and the trail will have disappeared.” Left high to open the route down after the storm, Roskelley and Ridgeway suggested instead that “the two of us just go for the summit!” In Camp I, many not designated two weeks earlier as members of the “summit team” were bitter: much had changed in the interim. In particular, many felt much stronger. They argued with conviction: “Just because I didn’t race early on the trip doesn’t mean I’m not as strong as anyone now;” or “A woman should go to the top.” Pinned between my “team mates” and “camp mates,” the future looked pretty bleak. Rob Schaller spent the next several days shuttling between tents, moderating radio calls, and evolving a compromise that would let one expedition, not three, make a final push for the summit. In a taut evening meeting, Whittaker rescinded his choice of the “summit team,” agreeing to let “the strongest at Camp VI go for it.” On the radio, Roskelley and Ridgeway relented and agreed to break out the trail between Camps III and II. In the shadow of the blizzards and impending failure, we had each sunk far below the level of unity we aspired to, but after 48 days above Base Camp it was probably inevitable, especially with virtually every climber feeling healthy enough to reach the summit.

After seven days of storms, the daybreak dawned wintry cold and crystal clear on August 26, but we were acutely aware this was only a temporary respite from winter. In 1976, the Poles had almost reached the summit on August 16, but had been repeatedly driven back in the month after that. Anxious to take full advantage of the weather and to join our “team mates” before they moved higher, Wickwire, Anderson and I climbed from Camp I to Camp IV, arriving in 60-mile-per-hour gusts at dusk. To our surprise, Dianne Roberts duplicated this feat, arriving well after dark with Big Jim. However little we thought of her wisdom in crossing so late, her ability to climb from 18,000 to 22,800 feet in one day left no doubt that the women could match the men. On August 28, we all moved to Camp V at 25,200 feet, and Dianne established an altitude record for North American women, but once again the winds were blowing from the south, so this seemed likely to be the only accomplishment of the expedition.

The storms returned that evening to bury our lonely tents on the dome. During a short respite the next afternoon, Wickwire and I made a dash for our Camp VI site, under a prominent rock triangle 900 feet above us. It took only 90 minutes to climb the first 800 feet, but the final few rope lengths went through waist-deep snow and were exhausting at 26,000 feet. For an hour, we literally shovelled out a path with our frozen gloves. “At least we’ve reached 8000 meters and won’t be disgraced!” we commented, accepting the Polish estimate for the site, although it later became clear they had been optimistic. A few bags of food and two oxygen bottles formed a cairn as we began our retreat, which took on dimensions of a route. The next morning nobody was above Camp IV, and two days later half the expedition was again at the bottom of the ridge at Camp I. With the porters scheduled to arrive September 10, Whittaker told the Bechs, Ridgeway, Roskelley, Wickwire and me to remain in Camp IV for one final shot, but the snowfall—four feet in one night—made it unclear whether we could take advantage of it. “The tent is almost buried,” we radioed from Camp IV. “Same here,” Whittaker replied from Camp III. “Only 3 days’ food left at Camp IV,” I noted in my diary.

The storms returned that evening to bury our lonely tents on the dome. During a short respite the next afternoon, Wickwire and I made a dash for our Camp VI site, under a prominent rock triangle 900 feet above us. It took only 90 minutes to climb the first 800 feet, but the final few rope lengths went through waist-deep snow and were exhausting at 26,000 feet. For an hour, we literally shovelled out a path with our frozen gloves. “At least we’ve reached 8000 meters and won’t be disgraced!” we commented, accepting the Polish estimate for the site, although it later became clear they had been optimistic. A few bags of food and two oxygen bottles formed a cairn as we began our retreat, which took on dimensions of a route. The next morning nobody was above Camp IV, and two days later half the expedition was again at the bottom of the ridge at Camp I. With the porters scheduled to arrive September 10, Whittaker told the Bechs, Ridgeway, Roskelley, Wickwire and me to remain in Camp IV for one final shot, but the snowfall—four feet in one night—made it unclear whether we could take advantage of it. “The tent is almost buried,” we radioed from Camp IV. “Same here,” Whittaker replied from Camp III. “Only 3 days’ food left at Camp IV,” I noted in my diary.

Meanwhile, discussions inside the tent were warm if not heated. Roskelley saw the final pitches on the northeast face as rightfully his, as the one “professional” among us. I didn’t like his proposed four-man assault above Camp VI without fixed ropes for the rock bands, since it seemed too similar to the Polish failures. Failing to reach agreement on strategy, we finally decided that four men were not significantly stronger than two in a one-day assault on that route. Wickwire, the Bechs, and I would try to finish the climb by the Abruzzi Ridge, however “tainted” a finish it might be. When the five-day storm lifted on September 2, the two assault parties set out together for Camp V, alternating trail- breaking through the very deep snow. The respite was very short. Another storm blasted us that evening and continued all the next day, as we ate one of our three days’ supply of food at Camp V.

On September 4, though, we were again able to move upwards. The Bechs, Wickwire and I began a traverse across open snow slopes towards the Abruzzi Ridge, but Cherie Bech had moved only a few yards before she realized she had reached the limit of her endurance and turned back. She had never hesitated during the expedition to carry the same loads as men of nearly twice her weight but had not recovered from becoming extremely hypothermic on the long carry to Camp V. Watching her return to Camp V after setting an Australian altitude record, we were struck by the tragic dichotomy between will-power which would have carried her anywhere, and her body which was made of the same weak flesh as the rest of us. In fact, five hours of thrashing through leg-deep snow with 50-pound packs got us only half-way to the Abruzzi Ridge. It seemed doubtful we could make it and certain Terry Bech couldn’t return to Camp V before dark, so we abandoned the effort and retraced our steps, planning to join Roskelley and Ridgeway at their Camp VI in the morning.

Meanwhile, John and Rick were encountering the same deep snow. It took them an exhausting ten hours to wade up the short distance to Camp VI. Once there, it took several more hours to find the cache. We had the frustrating task of dredging from our memories the necessary coordinates and providing over the radio an accurate enough description to let them locate it under six feet of snow. Only after two hours of digging at nearly 8000 meters could they find the oxygen and food. Venturing forth on September 5 to break out the trail, they found conditions too dangerous in sunlight. On the morning of September 6, they left at 1:30 A.M., resolved to stake everything on a single day’s effort. Four hours’ struggle through thigh-deep snow precariously balanced on 45° ice slopes provided little progress and a growing sense of risk. Again they returned to Camp VI where they reported their failures to Whittaker. In the lower camps, this seemed to be the expedition’s coup de grace, and plans were discussed for leaving.

Out of radio contact, however, we had also been struck by the dangers above Camp VI. Within ten minutes on September 5, I saw three large avalanches scour the gullies that John and Rick might have been climbing in if they hadn’t had such a difficult time the day before. The entire finish looked very exposed after the recent storms, so I left Wick and Terry at Camp V to see if I could break a trial to the Abruzzi Ridge without my pack. It was much easier to make progress that way; so after becoming convinced we could make it, I returned with the good news and retraced the steps with Terry, Wick, and our packs. Wickwire broke trail through the remaining deep snow as we followed him with loads. While Wick descended for his pack, Terry and I climbed a few more pitches on very solid snow to a crevasse a few hundred feet below the crest, where at 25,750 feet we pitched a tent at seven P.M. as the last vestiges of light were disappearing from the sky. Crammed into the two-man tent, we made a shambles of dinner and preparations for morning. Spilled water soaked our gear and we finished cooking only at eleven P.M.

Leaving at 4:30 A.M., far later than intended, Wickwire and I moved upwards on crisp snow in the cold, crystal clear night. We each had one oxygen cylinder, not enough for the entire climb and descent, so we planned to carry them as high as possible without using them. Wick had problems with his stride at first, but it was too cold to consider stopping. Finally, the sun hit the rocks at 26,500 feet and we rested while he started his oxygen. A few pitches further in the couloirs leading through the rock bands, the snow quality deteriorated suddenly in the warming sun.

I was happy to give Wick the lead and he did a marvellous job picking a route through the narrow exit of those couloirs while I panted in his wake. On the final pitch, we had to climb a chimney with some dubious snow and ice slivers on the rock as footholds for our crampons. Suddenly, they collapsed under me. Landing in a heap, I wondered how I could possibly climb those few feet. Altitude and the 35 pounds on my back had completely drained me. Finally reaching Wickwire, I set up my oxygen. With mask on and oxygen flowing, I led up some steep slabs to the base of the ice cliffs. It soon became clear that the oxygen wasn’t working at all, and as Wick came up I made some rather fuddled attempts to see what was wrong. Noticing the air bladder wouldn’t fill, even at 8 liters flow per minute, I looked enviously at his, bursting like a balloon. As I followed him across the base of the ice cliffs with my feet in dubious snow, I continued my finagling with the oxygen. I located the rough position of the leak, several holes in the tube—probably caused by crampons—and in slow motion tried to visualize something in my pack that would fix it. While I soon was convinced that adhesive tape was not in my kit, it wasn’t until I broke through two of Wick’s steps, losing several precious feet, that I felt absolutely hopeless and realized there was no chance I could reach our next goal, a rock, much less the summit as long as the weight of my “security blanket” was on my back. Dropping my whole pack, I resumed my pursuit of Wick. The weight made such a difference that I almost immediately felt rejuvenated and caught him. Wick looked at me as if I were an apparition: “What are you doing?” “I’m going without the oxygen. It won’t work. It’s a gamble, but there’s no choice. … Tell me if I exhibit any bizarre behavior.” “You realize I’m going to the top regardless?” “Yes.”

Much time had been wasted with my problems on the last few pitches. The snow ahead was virtually impassable. Hoping for better snow on a ridge, I traversed over there, but for several hours its promise was not realized. Wick and I were rather ludicrously breaking two parallel paths to the summit, sometimes only 100 feet apart. Finally, after several hours of wading, I hit solid snow just below a small rock fortress at 27,500 feet. Joining my path, Wick caught me 500 feet further and set a solid pace to the summit as I shivered a step behind him, very cold without oxygen or a parka. The summit seemed close, but that was deceptive as it receded with each footstep. It was a real surprise suddenly to step out of shadow into the glow of the setting sun, onto the level, gold-tinted ridge crest. Only 100 feet away was a beautiful summit at the high point of the shallow crest from which walls plunged into darkness on every side. Basking in the fulfillment of a lifelong dream, the sun made the temperature seem 30° warmer and transformed the whole mood of our surroundings from stark barrenness to warm beauty. After hugging, we did the last few steps together.

Much time had been wasted with my problems on the last few pitches. The snow ahead was virtually impassable. Hoping for better snow on a ridge, I traversed over there, but for several hours its promise was not realized. Wick and I were rather ludicrously breaking two parallel paths to the summit, sometimes only 100 feet apart. Finally, after several hours of wading, I hit solid snow just below a small rock fortress at 27,500 feet. Joining my path, Wick caught me 500 feet further and set a solid pace to the summit as I shivered a step behind him, very cold without oxygen or a parka. The summit seemed close, but that was deceptive as it receded with each footstep. It was a real surprise suddenly to step out of shadow into the glow of the setting sun, onto the level, gold-tinted ridge crest. Only 100 feet away was a beautiful summit at the high point of the shallow crest from which walls plunged into darkness on every side. Basking in the fulfillment of a lifelong dream, the sun made the temperature seem 30° warmer and transformed the whole mood of our surroundings from stark barrenness to warm beauty. After hugging, we did the last few steps together.

I wanted to leave immediately. It was my third high Himalayan summit; I was cold; and it was 5:20 P.M., only 90 minutes before complete darkness. Wick insisted on more than the minimum number of photos— flags, microfiche with the names of our contributors, even an Indian feather—as my patience wore thin. “We have to go now!” “I want a panorama. Go ahead.” So, unwisely, perhaps, I left, thinking he would come in a few minutes, but knowing he was mentally prepared to bivouac.

For me the descent was a desperate race against the setting sun. On Dhaulagiri and Nanda Devi, descents had been whimsical affairs—opportunities to fix in my mind every detail of terrain I would never see again. This time every second required for a footstep was resented, and it seemed unbelievably far to my pack where my parka restored my warmth for the first time in hours. Below the chimneys, I descended into the darkness of a new moon and a growing ground blizzard. Suddenly, the ground felt strange, and realizing the tent was hidden from the ridge crest, I proceeded very slowly, like a blind man, down the slope, hoping to feel a familiar shape in the snow. Fearful of ice cliffs, I waited until I was sure I was below the tent before traversing off the crest towards the tent and some crevasses I knew would provide shelter.

Then I saw a flash of light 100 yards away and slightly above me. I felt indescribably happy that John and Rick were being so patient in trying to guide us in. About 8:30 P.M., I reached the tent and felt the adrenalin drain from my body as I crawled inside ice-crusted and chattering, where I told the incredulous ears of my companions that I last saw Wick “on the summit,” and thought “he was bivouacking.”

Meanwhile, Wickwire had been “engrossed in changing film to shoot a panorama,” and had stayed another 40 minutes, far longer than he intended. “It wasn’t until I started down and saw how far you were that I realized I would never make it.” Stopping on a level platform 500 feet below the summit, he scooped out a shallow hole and crawled into his bivouac sack. “I didn’t realize how little stuff I had until I dug into my pack.” The ground blizzard made it a desperate ordeal at almost 28,000 feet, especially after his oxygen and stove were exhausted. Yet in the morning, he was able to put on his crampons and begin his descent down the trough of our ascent. Passing Roskelley and Ridgeway on their way to the summit, he reported that it had been cold, but he was all right and didn’t need assistance. Reaching camp at around ten o’clock, he helped dig out the tents before crawling in for well-earned food and drink. His endurance had been incredible.

Roskelley and Ridgeway, leaving camp at three A.M. in the midst of the wind storm, dropped their unused oxygen cylinders at 27,000 feet and continued to the summit, reaching it in mid-afternoon. After taking a nap, they descended, reaching camp before dusk, the first rope team to climb K2 without supplementary oxygen or to return before dark. Yet this was only the culmination of impressive performances by both of them over the entire expedition and especially over the past two days. On September 6, they had left at 1:30 A.M. to try the northeast face route. After failing because of atrocious conditions, they had been told of our summit attempt which was in progress and visible from the lower camps. Their competitive instincts aroused, John and Rick literally dragged 60 pounds apiece of food, oxygen, and equipment down the slopes below their camp to our trail across the east face. They portered these loads to our campsite, where after a second sleepless night spent largely in trying to help us, they began their own summit bid in a storm that would have kept most mountaineers in their tents. Roskelley broke trail the entire way to the summit, a particularly striking demonstration of his strength. The only real drama on their climb, once Wickwire’s safety was assured, was mental: each experienced vivid hallucinations—voices, palm trees, even a disco band—on the final slopes below the summit.

Possibly feeling deprived of excitement during their ascent, John and Rick managed to create some shortly after joining Wick and me at Camp VI by changing fuel cartridges while another stove was burning. The resulting explosion destroyed their tent, and the flaming remains of a sleeping bag and socks formed a beautiful firefall as they slid down 2000 feet over precipices in the darkness. Four of us in a two-man tent left no room for cooking and completed the ravages of altitude, as we suffered yet another night of little food, drink, or sleep. The descent to Camp I took four days in our weakened condition. While we spent much time complaining about “the absence of support,” the tracks left behind by Terry Bech and Whittaker were an immense help in reaching Camp III, where the Bechs were waiting. After a short storm, we were happy to be united with our long-lost comrades at Base Camp on September 12. In looking back, one could see that our margin of success had been so thin that almost every person at some point had held the fate of the expedition in his fingers, but had not let success slip through them.

Wickwire’s bivouac created delayed medical problems that almost exceeded the curative powers of Rob Schaller, our doctor. At Camp III on September 10, Wick complained of “sharp pain” in his side, possibly a broken rib, but by Base Camp he was seriously ill, a real invalid who had to be carried to Concordia. Diagnosed later as multiple pulmonary emboli, probably caused by the extreme stress and dehydration of the bivouac, his illness took an increasingly severe course, in spite of Schal- ler’s dedicated ministrations, as he slowly struggled down the Baltoro. Our Balti porters responded in the finest possible fashion to this crisis, first waiting without food an extra day at Base Camp for the slow summit party and then marching on half rations all the way down the Baltoro because Wickwire could not do the “double stages” they had planned on. Finally, after he suffered near heart and lung failure, we requested an evacuation helicopter to meet us at Payu, the highest altitude at which they would land. The Pakistani Air Force sent two very promptly on a very marginal flying day. They flew Wickwire, Schaller, Roskelley and me from the 13th into the 20th century, leaving us with fond memories of K2 and our selfless porters who had made it possible to achieve victory and avoid tragedy by the narrowest of margins.

Summary of Statistics:

Area: Karakoram, Pakistan.

New Route: K2, 28,250 feet, Third Ascent of the Mountain via a new route, the Northeast Ridge, East Face and Abruzzi Ridge, September 6, 1978 (Reichardt, Wickwire) and September 7 (Roskelley, Ridgeway).

Personnel: James Whittaker, leader, Craig Anderson, Terry Bech, Chris Chandler, Skip Edmunds, Diana Jagerský, logistics manager, Louis Reichardt, Rick Ridgeway, John Roskelley, Robert Schaller, William Sumner, James Wickwire, Americans; Cherie Bech, Australian; Dianne Roberts, photographer, Canadian; Subadar Major Mohammed Saleem Khan, Liaison Officer; Honar Beg, Sanjer Jan, Gohar Shah, Tsheran Shah, Hunza porters, Pakistanis.