The Ogre

THE Himalayan climber, however well organised he might be, treads a delicate tightrope between an uneventful attempt or ascent, and disaster. In my own experience, on the south face of Annapurna and then on two Everest expeditions, friends had lost their lives, all of them at the very end of the expedition. We very nearly experienced the same pattern on the Ogre. It was lighthearted all the way to the top. Then Doug Scott slipped. Suddenly a successful ascent turned into a struggle for survival.

We were hardly an expedition in the traditional sense. It was more like an Alpine trip with a group of friends using the same campsite and then making their own routes or climbing together as circumstances might dictate. Doug Scott had initiated the expedition, inviting six of us to join him, but then realising that seven was on the large size for a mountain of 24,000 feet. One obvious way out was to split the team and take two different routes on the mountain. This seemed to work out well since Doug and Tut Braithwaite were attracted to a magnificent rock prow that led straight up into the middle reaches of the peak, whilst Dougal Haston, Clive Rowland, Mo Anthoine, Charlie Clarke and I preferred a more devious and technically easier line to the left. Charlie, who would have been our doctor, was forced to drop out for personal reasons and, tragically, Dougal Haston was killed in a skiing accident in January of 1977. Nick Estcourt took his place.

The Ogre (officially Baintha Brakk) had already had three attempts. Don Morrison had taken out two expeditions in 1971 and 1975 but had failed to find a reasonable route up the lower slopes of the peak. Then in 1975 a six-man Japanese expedition approached it from the south up the Uzua Brakk Glacier. They reached a height of around 21,000 feet, in the first instance making an attempt on the west ridge and then, finding it too steep, trying to climb the south face. Having run out of time and weather, they were forced to retreat.

The Ogre (officially Baintha Brakk) had already had three attempts. Don Morrison had taken out two expeditions in 1971 and 1975 but had failed to find a reasonable route up the lower slopes of the peak. Then in 1975 a six-man Japanese expedition approached it from the south up the Uzua Brakk Glacier. They reached a height of around 21,000 feet, in the first instance making an attempt on the west ridge and then, finding it too steep, trying to climb the south face. Having run out of time and weather, they were forced to retreat.

We reached our Base Camp on June 10. It was on a triangular patch of grass, squeeezed between the moraine and the rocky slopes of an unnamed peak. Don Morrison’s Latok II expedition was already ensconsed a few minutes away. The atmosphere of the camp was pleasantly reminiscent of the Chamonix camp site, with the difference that we were surrounded by magnificent unclimbed aiguilles. It took three days to establish an Advanced Base in the basin immediately below the southern face of the Ogre. This was where our two routes divided. Doug and Tut were going to ferry their gear for an alpine-style push up to a col at the foot of the rock prow whilst the rest of us, jokingly called the B team, were planning to run a line of fixed rope up to the crest of a spur leading to another col, before pushing out alpine-style from there.

For the first few days Nick, Mo, Clive and I worked together without any firm pairing, pushing the route up the crest of a spur that eventually led up to a col. We had all underestimated its scale. I remember back in England allowing a couple of days to force the route up this spur all the way to its top. In fact, it was to take us nine days to fix the route and actually establish a camp at the top of the arête. On the way up we were forced to put in an intermediate camp.

It was during this period that we had our first misfortune. The rock leading up to Doug and Tut’s col was very loose. On June 18, when Doug and Tut were carrying loads to their col, a large rock was dislodged, striking Tut’s thigh. He was lucky not to have it broken, but it was severely bruised and he could only just hobble back to Advanced Base. It was impossible to guess just how long it would be before he was fit again but Doug resolved to wait it out, ferrying loads on his own to the foot of their route.

Meanwhile, we were making good progress on our arête, running out a few hundred feet of rope each day on classic alpine mixed ground; short rocky steps, the odd steep little gully and long snow slopes which later in the season were to become ice.

Nick and I moved up to our camp on the ridge on June 20. The previous day we had carried 50-pound loads up to the camp, food for the four of us to last ten days—enough, we thought, to make an alpine-style push from the top of the ridge. We spent the next two days pushing the route up an interminable snow slope and then along a knife-edged ridge of hideously soft snow. On any climb it is very easy to become self-righteous about one’s efforts, slightly paranoid about the people in camps either behind or in front. Clive and Mo, undoubtedly had a different concept of the climb from Nick and me and preferred a steadier build-up, with more rest days.

They joined us at Camp II on June 21. It was good to see them for we all got on well as a group even if we did have different ideas about the climb. We learnt that Doug was climbing with Mo’s wife, Jackie, who had arrived at Base Camp with Steph, Clive’s wife, just a few days before. The following day Nick and I had a rest while Mo and Clive went to the head of our fixed rope and then climbed the final headwall of very soft snow on ice to a point just below the top.

They joined us at Camp II on June 21. It was good to see them for we all got on well as a group even if we did have different ideas about the climb. We learnt that Doug was climbing with Mo’s wife, Jackie, who had arrived at Base Camp with Steph, Clive’s wife, just a few days before. The following day Nick and I had a rest while Mo and Clive went to the head of our fixed rope and then climbed the final headwall of very soft snow on ice to a point just below the top.

We were now all set to move up to the col. It was essential that we move quickly if we were to avoid going back to Base Camp for more supplies since we had only eight days’ supplies for the four of us. Nick and I had already carried most of our share of food whilst forcing the route out to our own high point of the day before and could therefore move up to the next camp. Mo and Clive, on the other hand, wanted to drop back down to Advanced Base for a rest. So we set out the next day as a twosome, hoping to complete the rest of the climb without any further fixed ropes.

It was a great feeling to pull over the final wall of that south face and stand on the broad glaciated shoulder that was to lead us to the final mass of the Ogre. We were now at 21,000 feet, level with the tops of the Baintha Aiguilles, only just below the crest of Conway’s Ogre, the highest peak of the Aiguilles. Over them, we could see a forest of snow peaks, hardly any of them climbed, most unnamed, and then, in the far distance, was Nanga Parbat, almost lost in the haze but towering, massive, dominating all its neighbours. We felt released from all external pressures, dependent on each other alone, committed to the seemingly simple objective of the Ogre.

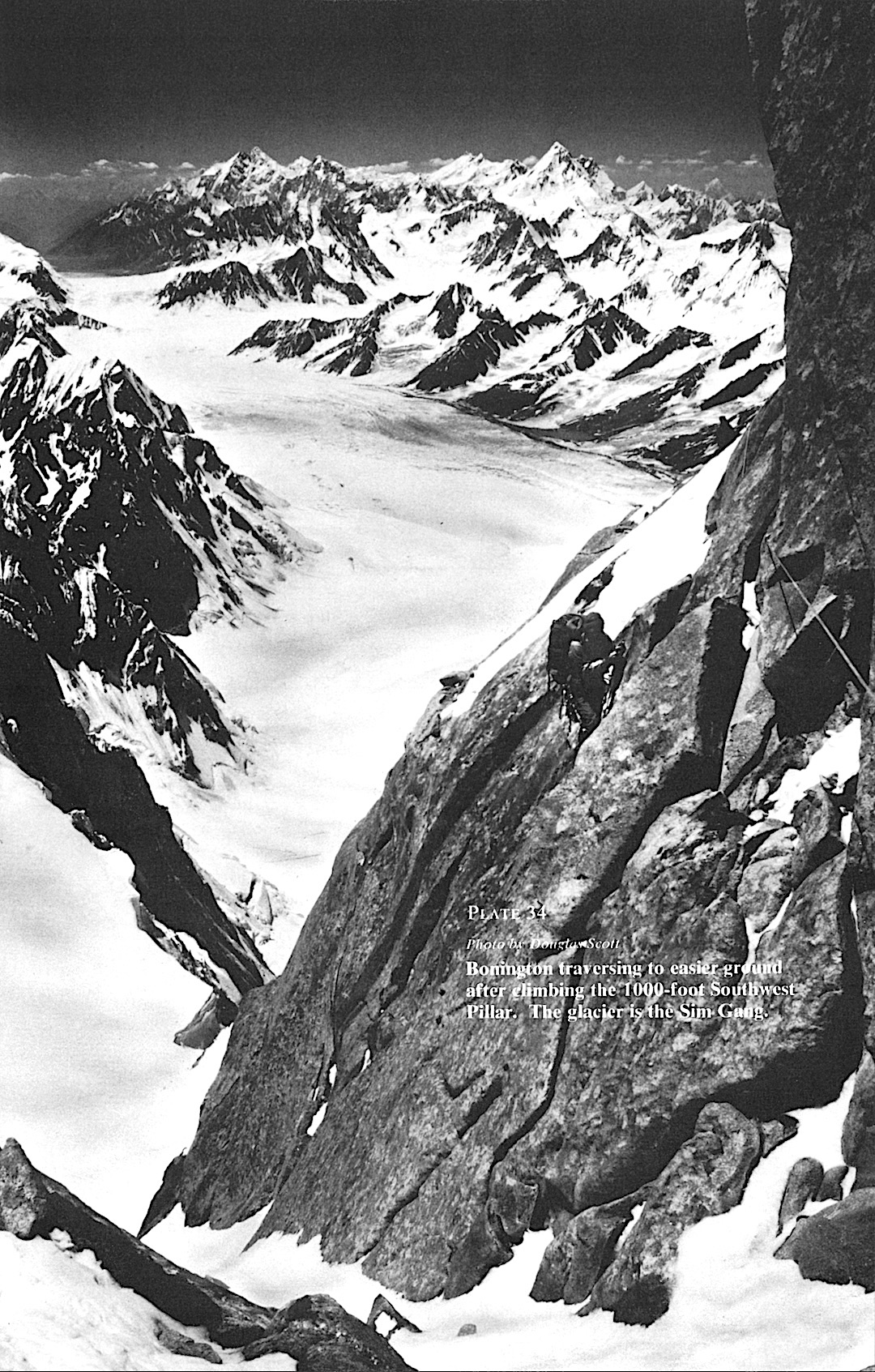

The following day we skirted our way in the grey light of dawn onto a great flat plateau that lay at the foot of the final keep of the Ogre. It was an exciting moment as we came to the other side and were able to look down onto the Sim Gang Glacier. It was like an Antarctic landscape, snow and rock without a hint of vegetation. In the distance Kanjut Sar and Kunyang Chhish, pyramids of snow veined with rock, and glaciers without end, writhing sinuous between nameless unclimbed peaks. There was a feeling of vast space; of endless mountains.

Once again we had underestimated our mountain. We had thought the route onto the shelf across the west face was going to be easy but it was much steeper than we had anticipated, with soft snow lying on ice; and then Nick saw some rope lying over a rocky slab—obviously the fixed rope of the Japanese. The bottom was attached to an expansion bolt (a heresy that even Doug and Tut were later to condone by its use). We spent the rest of the morning excavating rope from the snow as we slowly plodded up towards the shelf. The following day we carried loads to the end of the shelf, to the southwest corner, from where we planned to tackle the southern face of the mountain. The shelf was set at an angle of around 40°. In fine weather it was easy but would have been unpleasant to reverse in a storm. Peering round the end of the shelf, we could see Latok I, a slender spire of rock from this viewpoint, and in the distance, K2. We moved up to the shoulder on the morning of June 27 and dug a snow hole at 21,800 feet. We also decided to run out our two ropes to save time the next day. Nick led the first pitch across ice-covered rocky slabs, and then it was my turn. To get onto the snowfield we had to cross about fifty feet of holdless slabs to which the odd patch of snow clung. I started a series of precarious tension traverses from badly placed pegs to get across, muttering my protests to Nick, who urged me on—if I had come back down he’d have had to have a go.

We had planned to set out the following morning, but Nick was feeling tired and we had now gone for four hard days without a rest. We therefore decided to lay up for the day and set out on the 29th. So far the weather had been perfect, but that morning there was an ominous cloud build-up to the west. However, we could not afford to sit and wait it out. We now had only four days’ food and fuel left and I had no desire to go back down to Base Camp when we seemed so close to the summit.

We had planned to set out the following morning, but Nick was feeling tired and we had now gone for four hard days without a rest. We therefore decided to lay up for the day and set out on the 29th. So far the weather had been perfect, but that morning there was an ominous cloud build-up to the west. However, we could not afford to sit and wait it out. We now had only four days’ food and fuel left and I had no desire to go back down to Base Camp when we seemed so close to the summit.

We set out at about five in the morning, crossing the rope we had left the day before and then leading through up yet another endless snow slope. Nothing felt secure. It was snow on hard ice. To save time we used axe belays, but it is unlikely that they would have held a fall. And through the day the spindrift steadily built up, filling in the steps as quickly as we made them, sweeping down in little avalanches that threatened to pluck us off. At about three-quarters height the way was barred by a rock step. We had chosen the left side where it seemed more broken. By the time we reached its foot, it was already late afternoon and, to my relief, Nick’s turn to lead. He first tried a shallow groove filled with snow but it was too soft to take his weight; he tried another line and that also failed. By this time we were in cloud and the light was beginning to fade. At last he found a possible route, placed an ice peg about 80 feet above me, tensioned off it round a bulge and on up another fifty feet of soft snow over rocks whilst I nursed my axe belay and wondered what the pull would be like if he fell off. I reached him, did another nerve-racking pitch and it was nearly dark; there was no question of reaching the crest of the ridge that day and we had to make do with a shelf cut in the snow below the rocks of the west peak. I had a Gortex outer to my sleeping bag and as a result was able to keep dry. Nick on the other hand had only his sleeping bag and inevitably it became damp from condensation as a result of using the bivvy sack to keep out the snow.

The following morning we started traversing upwards towards the main peak. The closer we got the more discouraging it appeared. Back at Advanced Base and on the shoulder we had convinced ourselves that the final rock tower must have lines of weakness, perhaps around the back somewhere. I couldn’t believe that a 23,900-foot summit could have no comparatively straight-forward way to its top. As a result we had brought with us only fifteen rock pegs, no étriers and very few slings. But now, as we drew closer, it seemed more and more monolithic. Even reaching the little col below the summit block was not going to be easy. We had now very nearly reached the col between the west summit and the main one. We were only 300 feet below the summit but it was 300 feet of steep, technically difficult rock at a height of nearly 24,000 feet. It was past midday. I think the idea came to both of us at just about the same time. The west summit, which is about two hundred feet lower than the main summit, had an easy snow slope running up to it. We had only one cylinder of gas left for fuel, food for just a day and, what later experience proved, hopelessly insufficient hardwear. We decided to take the easier option and at least be sure of a summit. We dug a snow hole that afternoon and went to the top of the west summit the next morning before descending all the way back to the shoulder. It had been a good few days; we had undoubtedly done the sensible thing but there was a gnawing feeling of anti-climax. We hadn’t pushed ourselves to the limit; the thought of that squat, solid lump of rock on top of the Ogre worried away at me.

We were also worried about the others. Why hadn’t they come up? Could there have been an accident? We reversed the long traverse the following morning and as we came to its end, our questions were answered. There was a camp on the broad col immediately below the end of the traverse. On reaching it we found Mo, Clive, Tut and Doug. They had been equally worried about us but had reckoned there was very little they could do if we had come to grief and were, therefore, pursuing their own route. Clive had always favoured a route straight up the steep rocks of the west ridge on the grounds that it was both safer and more interesting. Doug concurred with this and had decided to abandon his rock prow since Tut’s leg was still giving trouble and to join forces with Mo and Clive. The previous day they had actually started work on the west ridge, greatly helped by a providential find of about a thousand feet of Japanese fixed rope. They, obviously, and very understandably, weren’t heart-broken at our failure to reach the main summit. They had bad news for us. It was not an accident to our team that had delayed their return to the mountain; it was a tragedy within the Latok II expedition. A few days earlier Don Morrison had fallen into a crevasse and had died.

We sat and talked and I couldn’t help noticing that their pile of food was very similar to what we had taken with us and that there wasn’t nearly enough for a sustained push to the top. I was also beginning to think of another go for the summit. If I could persuade them to come down for more food and fuel, Nick and I would be able to have another go. For once sound strategy and Machiavelli went hand in hand. Finally they all agreed to go back down for more. We reached Base Camp in the afternoon and, two days later, Clive, Mo and Doug were on their way back up. We were to follow the next day, giving Nick and me all of two days rest in Base Camp. We were both very tired and, in addition, Nick had a badly infected throat.

We started back up on July 5, spending a day at Advanced Base, rescuing the gear and food that Doug had left on the col below the rock prow. That day Tut and Nick realised that they were not up to another attempt. Tut’s leg was still very troublesome and Nick’s throat was getting steadily worse. I set out by myself in the early hours of the following morning for the 13-hour haul to the camp on the col: 4000 feet of climbing with a heavy sack.

Meanwhile the others had moved one tent up to the shoulder below the West Ridge at 22,500 feet and were making good progress on the rocks of the ridge. Doug did all the leading for two days on steep but broken rocks with several stretches that gave VS climbing. When I joined them on the shoulder, Doug had taken a rest day while Mo and Clive had pushed the route out to a point just short of the crest of the steep section. Mo had ended with a magnificent lead up a long ice gully.

We were now delayed by two days of threatening weather. Since we only had one tent for the four of us, Mo and I were bivvying out under the stars—very romantic but chilly. On the second day, Doug and I dropped back down to the col to pick up the other tent.

At last, on July 11, we set out for the summit. Once again we underestimated how long it takes to do anything at altitude. That day we had hoped to get over the west summit to the snow hole that Nick and I had left, but it wasn’t to be. There was one more hard pitch to reach the top of the step. Doug led it; an awkward traverse on very steep ground requiring a series of thin, semi-tension moves. I followed unhappily on Jümars, rappelling short sections and tumbling at one point when I suddenly took up a lot of slack in the rappel rope. We were able to drop the rope from a higher point to give Clive and Mo an easier passage.

With four of us and the closer presence of fixed ropes it all felt very much more relaxed and light-hearted. Doug and I brewed up whilst the other two jümared up to join us. We obviously weren’t going to make the west summit that day but dug a snow hole on the shoulder 500 feet below it for Mo and me whilst Clive and Doug erected their bivvy tent.

It took us the entire next day to reach the snow cave on the other side of the west summit: a long traverse, part of it over 40° ice, and then up a 300-foot slope of snow thinly covering ice. We had a brew on the shoulder just below the west summit before Doug led off up a knife-edged ridge of unconsolidated snow over its top. This was my second visit to the west summit of the Ogre.

That night we enlarged the snow hole that Nick and I had made, ready for our summit bid the following morning, agreeing that Doug and I should set out first, taking three of the four ropes with us, so that we could fix them whilst Mo and Clive caught up.

We set out at about five in the morning on a long, slightly descending traverse below the cockscomb of rocks that crested the ridge until we came just short of the final tower. A gully and then steep but broken rocks led up towards the crest. Doug led up this on good rough granite that was severe in standard. On top of the ridge it was possible to traverse surprisingly easily to a point where we could rappel down on the col immediately below the final rock tower. By the time I got to its base, Doug was already geared up with a good selection of nuts and pegs.

As I arrived, he tossed the two ropes at me and plunged round the corner. The ropes promptly tangled and whilst I struggled with the knitting, Doug cursed, hanging from a fist jam, all good stuff at 23,700 feet above sea level. Once the rope was untangled, he made good progress to the top of the groove and I followed on Jümars. The time was slipping by at an alarming rate. We weren’t much higher than the snow cave of the previous night and had only climbed three rock pitches in addition to the snow traverses; it was already long past midday. Mo and Clive were just reaching the top of the ridge itself; Mo had had to lead the final pitch onto the crest of the ridge without any protection or aid. We had been forced to pull the rope up to give us two ropes for the final tower and the second pair had no slings, pegs or nuts. We were now going to be forced to pull up the rope from the first pitch of the final tower if we were to have any chance at all of completing the climb that day. I think we were all aware that we had to get the peak climbed as quickly as possible, for we were now very nearly out of food.

Doug started up the final steep wall. It was just off vertical, completely smooth, but cleft by a thin crack giving good nut placement. He went up smoothly and methodically for about eighty feet and then came to a halt. The crack had run out. There was another about twenty feet to the right—Yosemite here we come! He descended from his top anchor about thirty feet and started to pendulum across the wall, walking back away from the crack and then running across the face, a skyhook outstretched in his hand to catch the crack. He had a dozen goes before he finally made it, pegged his way up the crack, traversed back into the resumption of the main one, pulled over a little overhang and was up. But time was running short; the sun was dropping down into the west, lighting the rock with the rich yellow of the late afternoon. Clive and Mo had dropped back down to the snow and were traversing back to the snow hole. It was four o’clock—only three hours of daylight to get to the top and back down again.

The crack had taken us onto a small snow shoulder. I led through and headed towards the final summit block. As there was no way of climbing it direct, we had to traverse around it. I worked my way around a little gangway to the foot of an overhanging groove—no holds and time slipping away fast. I brought up Doug. It seemed that we’d need a shoulder. He hadn’t put his crampons back on and so I belayed at the foot of the groove. Doug climbed over me, up onto my shoulder, a Herculean pull and then a scrabble on powdery snow lying on rock. He was up. I followed, carrying the sack. No time to fix Jümars. He just hauled me and I arrived panting, exhausted at the stance. Doug immediately set off again up the final couloir. Snow at last but it was deep, insubstantial powder lying on rock, insecure and strength-sapping. It took Doug nearly an hour to reach the top. I wasn’t much quicker, following on Jümars. But at last, at seven o’clock on the night of July 13, we were standing on top of the Ogre.

The sun had already dropped behind Kunyan Chhish; there was little time to enjoy the magnificent panorama which the Ogre offered, being by far the highest peak in the Biafo area. K2 was a triangular black silhouette in the far distance, fast merging into the blue-grey of the night; Nanga Parbat to the southwest was outlined against the fading brightness of the sky, and the glaciers, in deep shadow, writhed away from us on every side. Looking down the other side, there was little doubt that we had reached the summit by the easiest possible route. But there was no time for reflection. Tired of being tail-end Charlie, I offered to start down from the top but Doug had been there for nearly an hour and was anxious to get moving, so he started down.

We fixed the rappel rope just below the summit and Doug disappeared from sight. We were going straight down the headwall and then crossing the shoulder to the top of the steep wall. Whilst Doug worked his way across the snow of the shoulder and then stepped down onto the peg we had left ready for us at the top of the crack, I contemplated the view, my eyes wandering over the myriad of peaks around us. My thoughts were interrupted by a Tarzan-like yell. I glanced back to where Doug had been. No sign of him. I felt the rope; it was taut; he hadn’t gone off the end. He’d obviously slipped and done another, this time involuntary, pendulum. Was he badly hurt? Could he get down to a ledge to take his weight off the end of the rope? Could he find a belay point? For a few seconds I felt very lonely standing only a couple of feet below the top of the Ogre. “This might well be it,” I told myself, but then began working out how I could get back down a rope under tension. The safety springs on both my Jümars had failed. Doug didn’t have any.

Then there was a shout from below. “I’ve broken my legs.”

“Can you get your weight off the rope?”

No reply; a long pause and then the rope felt slack in my hands. I could get down to him and see what was wrong. I carefully put on my figure-of-eight, double checked everything and slid down the rope. Doug was sitting on a small ledge, secured by a couple of good nut anchors. I had already thought of all the problems of getting a badly injured man back down. There was no way I, at that point, or the three of us once we got off the summit pyramid, could have carried a helpless man. There were too many traverses to lower him. If we were to go back the way we had come, we were even going to have to climb up over the west summit. I remember reassuring Doug that we’d get him down somehow and privately wondering how the hell we’d do it.

We obviously couldn’t spend the night where we were, but just below us was a little spur of snow. Perhaps we could dig out a platform on it. I rappelled and Doug followed, wincing with pain, but managing to slide down on his back and then, with a pull of the rope, crawl across to the platform I had dug. It was reassuring for the future.

Then followed the coldest night that I have ever spent, though Doug reckoned his night on top of Everest was even colder. We had neither food, stove or any down gear. We sat through the night, facing each other, with our feet in each other’s crotches, massaging each other’s toes throughout the night. With his two broken legs, Doug was particularly worried about frostbite. The night dragged out slowly. As soon as there was light enough to see, we struggled back into our boots and started down. I went first, fixing the rappels and Doug followed. Once we got to the bottom we were confronted with a difficult decision. We could either go back the way we had come or go straight down the face, following the route that Nick and I had used. I rather favoured this latter course though it would have involved a lot of traversing with indifferent belays. Anyway, I left Doug at the foot of the wall to go and get Mo and Clive. I met them halfway back to the snow cave. I continued on, leaving them to collect Doug.

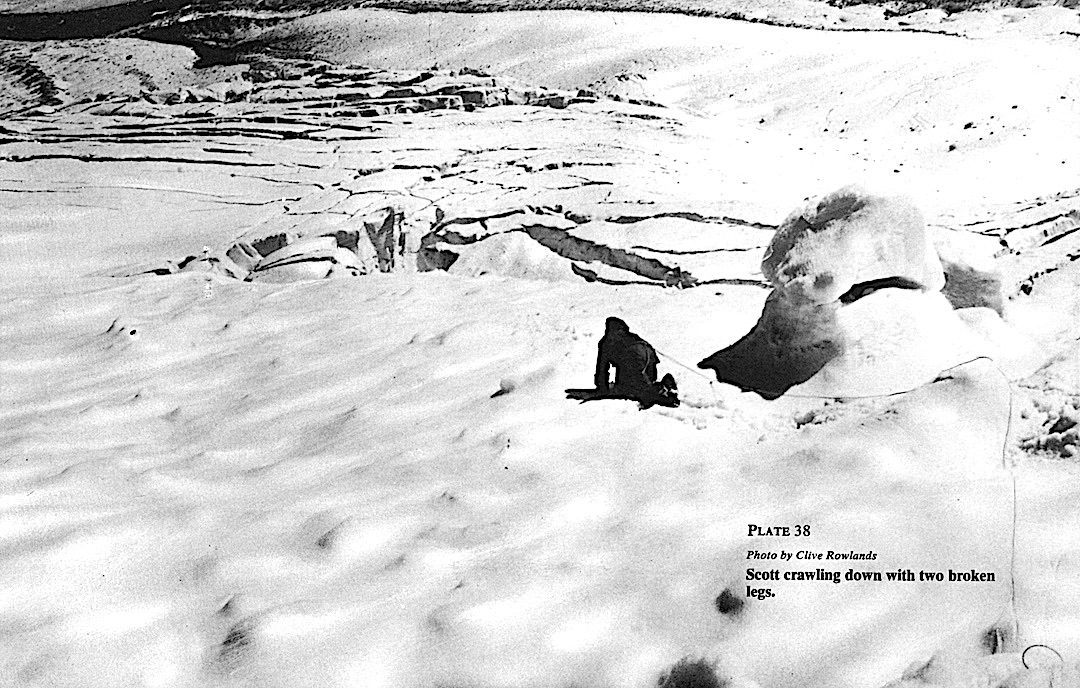

By digging out big bucket steps for Doug he was able to crawl on his knees all the way back to the cave. The others favoured a return over the top of the west summit since we should be heading towards fixed ropes and our two tents. Also, of course, this was ground they had already covered.

By digging out big bucket steps for Doug he was able to crawl on his knees all the way back to the cave. The others favoured a return over the top of the west summit since we should be heading towards fixed ropes and our two tents. Also, of course, this was ground they had already covered.

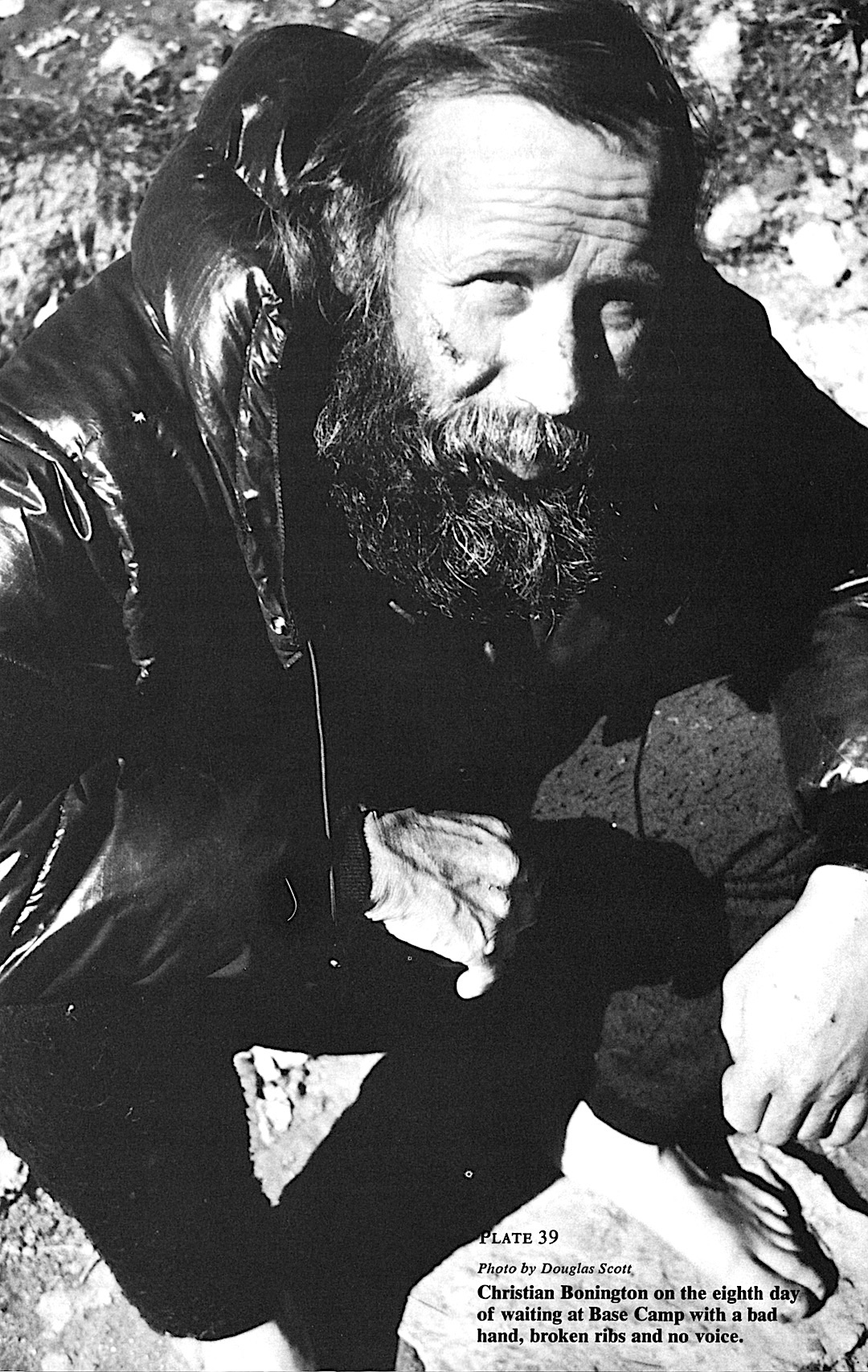

I spent the rest of the day in a semi-comatose state, snuggled into the warmth of my sleeping bag. I had almost completely lost my voice and could only whisper. Mo took over the chore of massaging Doug’s feet. Through the day high cloud had slowly crept over the western sky, a threat for the morrow.

The weather broke during the night. In a snow hole you hear nothing of the storm outside but the spindrift creeps insidiously through the smallest chink in the doorway. Mo had the misfortune to be on the outside and that night got his sleeping bag covered in snow.

We started brewing water for tea first thing in the morning. The plan was for Mo and Clive to go out in front and fix a rope up to the top of the west summit. Doug would then jümar up it and I would bring up the rear, clearing the ropes and pegs. Our crampons and ice axes were in a pile outside, now covered in snow. Mo couldn’t find his crampon. It was as if the Ogre had hidden it to tease us puny mortals. Clive started up the snow slope, I belayed while Mo adjusted one of Doug’s crampons. It was almost a complete white-out, the snow pouring down the slope in a continuous torrent, filling up the tracks as fast as he made them. Whereas it had been easy kicking steps when Nick and I had climbed this same slope just two weeks earlier, now Clive was sinking up to his thigh in a morass of soft snow. Two hours later he was only sixty feet above me. In these conditions it was hopeless. He returned to the snow hole and we spent the remainder of the day resting, making the occasional brew and playing endless card games. That night we had our last solid meal—if it could be described as solid. It was a soup thickened with mashed potato powder. Now all we had left were a few tea bags and some meat-extract cubes.

Next morning the storm still raged. But there was no question of sitting it out and Clive took the lead once again, doing a marvelous job forcing his way upwards through the deep snow to the top of the west peak. Mo followed and then Doug started up the rope. He was using two Jümars, kneeling in the snow, pulling himself upwards by sheer strength. He was unable to follow the line of steps made by Clive, which had filled in anyway, but had to follow the direct fall-line of the rope. It was a desperately slow, cumbersome business and for the last few feet he was hauled up by Mo and Clive, the only direct aid he needed on the entire ascent. I followed behind, removing the intermediate pegs. By the time I reached the summit it was midday. It had taken six hours for the four of us to climb two hundred feet, a distance that had taken Nick and me less than an hour on our ascent.

Mo and Clive had already started down and I found Doug sitting forlornly on the summit; they had already pulled their ropes down and I think we both felt that faint panic of abandonment. Doug shouted down for them to wait for us and a reassuring cry penetrated the noise of the rushing wind. I flung our ropes down the broken ridge, rappelled down to Clive, who was waiting, and then Doug followed. At least we were now going downwards, but the fear of a rope jamming when we pulled it down was constantly with us. Mo had by now disappeared in the swirling snows below, taking two of the ropes with him and looking for rappel points. We were desperately short of pegs for most of them had been left either at the top of the rock wall, where Doug had slipped, or in my rucksack on the col. We had only five rock pegs, a few nuts and one ice peg for the entire descent.

We followed Mo, searching at the end of each rope-length for the next anchor point, guided by his shouts until we reached the spot where we had to start traversing. Mo’s lead across the snow-clad ice was superb and we then abandoned one of our ropes to give the rest of us a handrail across. We had been particularly worried about how Doug would fare on this section of the route but Clive cut out great bucket steps for him on the traverse and he was able to crawl along in fine style, with a back rope from me.

It was very nearly dark when we reached the site of our previous snow hole on the top of the rock step in the ridge. Mo was already digging out the snow hole that he and I had used on the way up. Now, of course we were going to have to make it large enough for four. We were all tired and cold, anxious to get into the warmth of our sleeping bags and yet if we were to be comfortable we needed a good sized cave, but that took time and effort—and how much effort could we afford? It was impossible to squeeze all four of us into the somewhat enlarged hole and keep off the walls. Mo and I on the outside were particularly badly placed for the spindrift and by morning both our sleeping bags were soaked. Mo had no feeling in either foot.

The storm was as bad as ever in the morning. Strengthened by a brew of milkless, sugarless tea, we set out once again, Mo pushing on ahead and then Doug, belayed between Clive and me, crawling along the crest of the ridge and then dropping down to the final steep section that would lead to the top of our fixed ropes. It was here that we had one of our narrowest escapes. Mo was making the final rappel onto the top of the fixed ropes, down the ice gully that he had originally led. We now had three ropes left. He started down on a single rope which we intended to abandon, reached the end of it, couldn’t find an anchor point and so tied an overhead knot in the end, clipped in a karabiner and then snapped in the doubled ropes so that we could recover these for use later on. Unfortunately they were not the same length and the shorter end did not reach the top of the fixed rope. Mo therefore climbed down the last few feet but tied off the longer end. He shouted up to warn Doug of what he’d done but his voice was lost in the wind. Mo then started down the fixed rope to get the tents dug out, which we hoped to find in place at the bottom of the pillar.

Doug now started down, didn’t notice that the short end was hanging loose and rappelled off it; with his weight on just one rope he shot down out of control but miraculously managed to grab the fixed rope as he passed it and, equally providentially, did not hit his damaged legs on the way down.

Clive then followed, warned by Doug of the state of the ropes, readjusted them and tied the long end off once more, but left the short end dangling. It was then my turn to come down and I, in my turn, failed to notice the dangling end. I went straight off the end of the shorter one, fell about twenty feet before the tied off rope held me. One moment I was rappelling and the next shooting down out of control; I hit a rock with a terrifying crunch and was then hanging suspended on the rope.

At the time I felt hardly any pain and didn’t realise I’d done anything more than bruise myself. Not wanting to go back for the ropes but knowing we were going to need some to get Doug over a bergschrund down to the camp, I hacked off twelve feet of loose rope. I then started down the fixed rope just behind Doug. In a brief lull the sun broke through the clouds; we caught a glimpse of snow-plastered peaks around us and, best of all, could see to the bottom of the pillar where Mo was already digging out one of the tents. We were to have shelter that night. And then the storm closed in once more. Doug hauled himself across the traverses remarkably well and slid on down the final ropes to their end, poised over the bergschrund. The storm reached a climax; you could hardly open your eyes in the driving snow. Yet somehow we had to lower Doug down over the bergschrund on just ten feet of rope. Clive, Doug and I were all hanging from the same peg. At last I got him down, then climbed after him; a few more feet of steep snow and it was then easy going to the tents. We collapsed thankfully into them and settled in for the afternoon. Our sleeping bags were soaked but this didn’t seem to matter too much. We even found some milk and a little sugar— enough for one brew.

It was the following morning when the effects of my fall hit me. Up to that point I had felt naturally tired but still had plenty of reserve. After clearing the tent of snow, when I got back in, my strength just drained away. The storm set in again. We had descended the most difficult ground but if we had to cross the broad plateau of the col in a white-out, we would have all too little chance. I couldn’t understand why I felt so ill but didn’t connect it with the fall. I began to suspect pulmonary oedema, in which case I needed to get down as soon as possible; but the others were skeptical. The rest of the day passed in semi-coma and increasing pain from my chest. That night I dosed myself with codeine and mogadon, the only drugs we had with us.

At last the weather was kind to us. On July 19 it dawned fine. We took down the tents and started to descend, Mo going first, then Doug and, in the rear, Clive and I. Our job was to clear the fixed rope we had left below the camp to use it lower down. I was feeling light-headed and incredibly weak but stumbled on, carrying a sack that was all too heavy, though not as heavy as that of Clive, and towing behind me three hundred feet of rope. By the time we got down to the bottom, Doug and Mo had unearthed the campsite on the col, hoping to find some food, but there were only a few scraps. Then back over the plateau, Mo and Doug breaking trail; Clive off at a tangent in search of the tent that he had dropped on the way down, and I, stumbling a few feet at a time, the slowest of all. But that night we could relax. We had reached the head of the fixed ropes down the arête on the face; the weather seemed settled and next day we should get all the way to Base Camp, join the others and, above all, have something to eat.

Mo and I left first, improving the route where possible and fixing a line of rope along the crest of the arête, which at the moment had no protection, while Clive stayed behind to help Doug. Mo shot off down the first rope whilst I followed more slowly. By the time I reached the arête, he had finished it and I followed, laboriously cutting steps to make the traverses on steep ice a little easier for Doug. It was particularly awkward for I had completely lost the use of my left hand. The wrist was badly swollen and I began to wonder if I had broken something in my fall. The descent seemed interminable. Mo was far ahead getting increasingly impatient, for he was anxious to get down as soon as possible to link up with the others at Base Camp and to arrange for Doug to be carried from the site of Advanced Base down the five miles of glacier to Base. It was midday before I reached the bottom of the fixed ropes. Mo and I abandoned everything we didn’t need in the immediate future—crampons, harnesses and, in my case, even a spare sweater. He then took me in tow and hauled me on down the slope. We were roped together but had Mo fallen down a crevasse I don’t think I could have done much about it. Once we were off the snow onto the dry glacier we unroped and Mo took off. I wandered on, slightly dizzy, but content to be alive in the hot sun, resting every fifty paces or so. It was three o’clock by the time I came into sight of Base Camp. I was getting increasingly worried for there was no sign of the others. Surely they couldn’t have abandoned us? Just as I came in sight of Base, I saw Mo in the distance on his way down the glacier. It could only mean one thing; that there was no one at Base and that he was racing off for help. Half an hour later this was confirmed. No tents, no people; but at least under the boulder that had been our kitchen was a cache of food and a note.

Nick and Tut had been placed in an impossible situation. When we had set off for the summit, we had allowed a week for the attempt and had ordered porters for July 13. They had seen us near the summit on the 13th, and obviously on our way down on the 14th. There was nothing to indicate that we had had an accident. The porters we had ordered were costing us £100 a day and anyway there was insufficient food to keep them at Base Camp for several days. They took what to them seemed the only solution—clearing Advanced Base and sending the bulk of the porters with Tut and Alim, our liaison officer, down to Askole, whilst Nick and six porters stayed behind.

And then the weather broke. The days stretched out and Nick became more and more worried. There seemed no possible explanation for our taking so long except some terrible disaster, an avalanche or multiple fall that must have killed us all. At last on the 20th—just a few hours before Mo got to Base Camp, Nick decided he must get help. He left a note which started with a cheerful, “In the unlikely event of your reading this I have gone down for help.” He could do nothing by himself and planned to bring Tut back up so that they could try to see what had happened to us.

Mo, in hot pursuit down the glacier, bivouacked two nights before he caught up with Nick and Tut at Askole. They were just discussing how they were going to tackle the appalling job of telling our wives when Mo walked into the campsite.

Meanwhile, Clive and Doug had staggered on down the fixed ropes and then Doug had crawled all the way back to Base, reaching it at ten o’clock that night.

We spent three days lying waiting at Base Camp, not knowing what had happened, when anyone would come, and then Nick with twelve porters appeared to rescue us. For Doug, two cold and desperately uncomfortable days on a makeshift stretcher; for me a walk in a daze down the Biafo Glacier and then it was nearly all over. The helicopter came clattering in but could only take one out at a time. Hopefully it would come back for Clive, who had frost bitten toes, and me—but it never returned; it had crash-landed at Skardu and was out of action. We limped on into Askole. I was now very weak and desperately slow. I must have broken some ribs in my fall. I was coughing up a lot of frothy foam, a sure sign of some kind of pulmonary trouble. Therefore I was to wait for the helicopter, which we assumed would fly in the next day, whilst the others hiked out. I waited six days of uncomfortable boredom that verged on near despair, before a helicopter finally flew in. Our adventures were at last over. The transition was fast. I was flown straight out to Islamabad and deposited on the golf course a few minutes from the British Embassy, a bearded, filthy skeleton, clad in red silk underpants and a dirty blue sweater, clutching an ice axe and a bundle of down gear. The golfers kept their distance whilst I waited for someone from the Embassy to pick me up.

We spent three days lying waiting at Base Camp, not knowing what had happened, when anyone would come, and then Nick with twelve porters appeared to rescue us. For Doug, two cold and desperately uncomfortable days on a makeshift stretcher; for me a walk in a daze down the Biafo Glacier and then it was nearly all over. The helicopter came clattering in but could only take one out at a time. Hopefully it would come back for Clive, who had frost bitten toes, and me—but it never returned; it had crash-landed at Skardu and was out of action. We limped on into Askole. I was now very weak and desperately slow. I must have broken some ribs in my fall. I was coughing up a lot of frothy foam, a sure sign of some kind of pulmonary trouble. Therefore I was to wait for the helicopter, which we assumed would fly in the next day, whilst the others hiked out. I waited six days of uncomfortable boredom that verged on near despair, before a helicopter finally flew in. Our adventures were at last over. The transition was fast. I was flown straight out to Islamabad and deposited on the golf course a few minutes from the British Embassy, a bearded, filthy skeleton, clad in red silk underpants and a dirty blue sweater, clutching an ice axe and a bundle of down gear. The golfers kept their distance whilst I waited for someone from the Embassy to pick me up.

On looking back at the expedition, inevitably the descent engulfs the climb. It was an epic that we shall all remember, for it is the epics that are truly memorable and those memories soon become affectionate, even humorous. At no time during the descent did any of us feel despair, nor for that matter, were we ever out of control of the situation (except for the odd few moments of uncontrolled descent). For my own part I must confess to acute worry once I started feeling ill after my own fall, for this was something inexplicable, but all one could do was to keep on descending. The worst period was the one spent waiting in Askole, alone, without even a book to read, unable to understand why a helicopter hadn’t arrived and unsure of what to do, if it didn’t. We were undoubtedly lucky that Doug hadn’t, broken both his tibia and fibula since with both bones broken in either leg the pain of movement would have been unbearable. The nightmare situation in any high-mountain accident is what on earth one does if the injured person can’t move under his own power and you can’t carry him. Fortunately in this instance, Doug, through his own efforts and exceptional stamina, got down the mountain with the very small level of help we were able to offer him. It was also fortunate that we had an ample stock of gas cylinders, for without them we should have been unable to melt snow. You can go for several days without food without unduly impairing efficiency. We should have been in serious trouble, however, if we had had no liquids for five days.

On getting back to Britain I was irritated, as all climbers are, by the insistence of laymen and the media talking of our conquering the Ogre. I felt that the Ogre had allowed us to climb it and then, like a great cat, had played with us all the way down, finally allowing us to escape, mauled but in one piece to play more games with other mountains in the future.

Summary of Statistics:

Area: Biafo Karakoram, Baltistan, Pakistan.

First Ascent: The Ogre or Baintha Brakk, 23,900 feet. Summit reached on July 13, 1977 (Bonington, Scott).

Personnel: Douglas Scott, Christian Bonington, Tut Braithwaite, Mo Anthoine, Clive Rowland, Nicholas Estcourt.