Danger Zones: Eldorado Canyon

Where & Why Accidents Happen in Colorado's Trad Mecca

EVEN AT A DISTANCE, the sound of a person hitting the ground after a 70-foot fall is unmistakable. On April 9, 2016, I was approaching the Whale’s Tail in Eldorado Canyon to follow a novice trad climber up his first lead in the Colorado state park. Hearing a commotion, we rushed over to the base of Redgarden Wall to see if we could help. A climber lay badly broken on the trail, rope still attached to his harness, while another climber held his head and we both assessed his injuries. A fun day out had gone horribly wrong.

Paramedics arrived to stabilize the climber. Rocky Mountain Rescue Group packaged and evacuated him to a nearby road, where an ambulance waited. A helicopter soon delivered him to a level-one trauma center. As our adrenaline receded and the climber’s long road to recovery began, so did my own journey to understand why such accidents happen in Eldorado Canyon and what might be done to prevent more of them, both here and at similar multi-pitch traditional climbing areas around North America.

“Eldo” is home to ruddy sandstone formations up to about 800 feet high, hosting well over 1,000 rock routes. Approximately 95 percent of the routes require climbers to place and remove their own protection (the rest are top-ropes or bolted climbs); a majority of climbs do not have fixed anchors at belay stations; and there are hundreds of multi-pitch routes and link-ups. Eldo’s complex cliffs present extra challenges to climbers, including route-finding, occasional loose rock, inconsistent protection opportunities, and complicated and exposed descent routes. Nevertheless, in key respects, the accidents that occur here—and the lessons derived from them—are similar to those in other traditional climbing areas, from North Conway to Devils Tower, and from desert sandstone to Squamish granite.

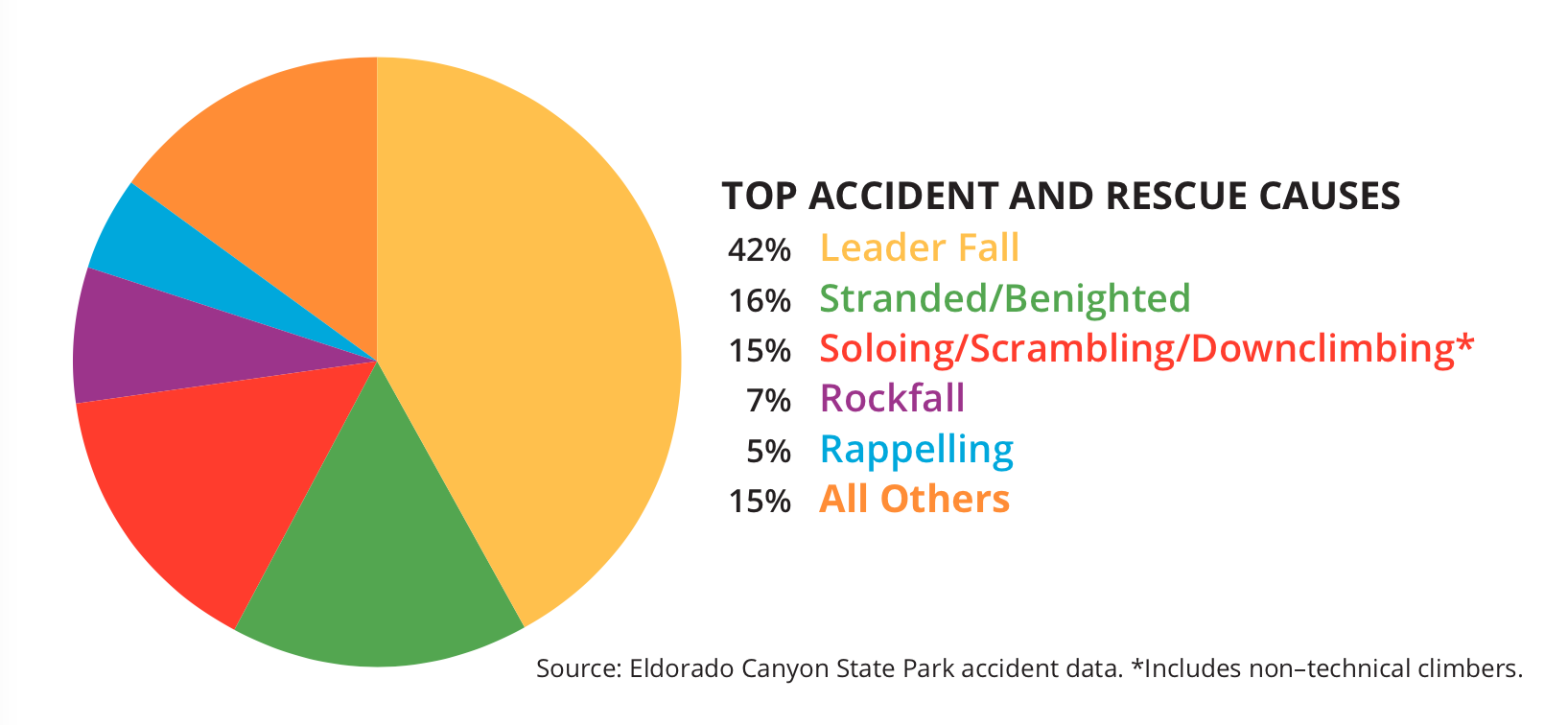

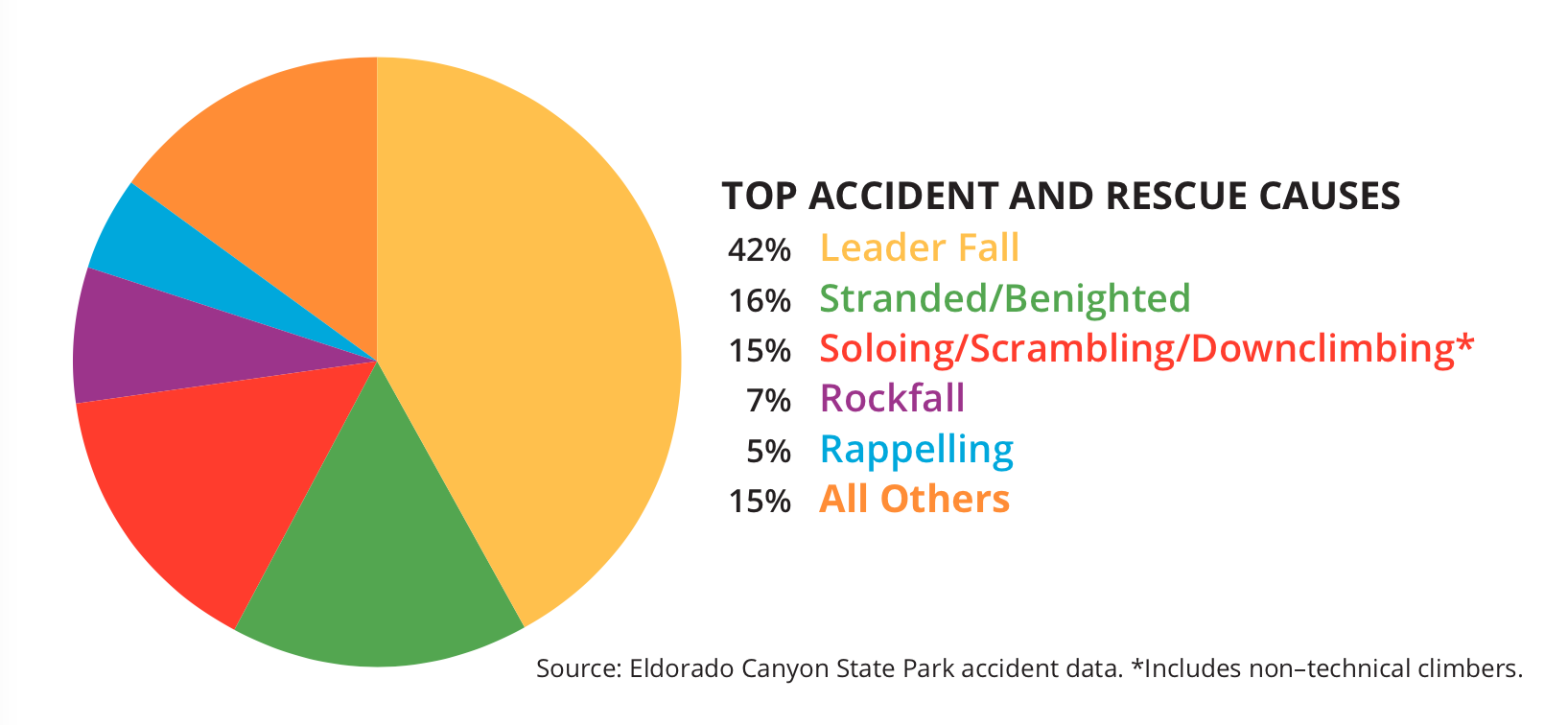

To better understand Eldorado Canyon’s accident history, I analyzed 75 incident reports published in the last 30 years of Accidents in North American Climbing. In addition, the Accidents editors met with rangers at Eldorado Canyon State Park and reviewed data prepared by rangers and by Rocky Mountain Rescue Group, the main search and rescue organization serving the park. Here, we present the most common causes of climber accidents and rescues in Eldorado, along with recommendations to prevent or mitigate them.

FALLS

By a large margin, falling while climbing is the most likely way to end up in the pages of Accidents, and Eldorado Canyon is no exception. Over half of all the incidents documented in the various Eldo studies involved falls—most of them leader falls.

In many of these cases, one or more pieces of protection pulled out during the fall, causing the leader to plunge farther than expected and suffer an injury. Often the piece that pulled was the first and only one on a pitch, leading to a ground or ledge fall. As the Eldorado rangers recommend at the state park’s website, “Never have only one piece of protection between you and a catastrophic fall.” Sometimes multiple pieces failed. The climber I encountered last April below Redgarden Wall had pulled out his top two pieces (both micro-cams) in a fall, causing him to plummet all the way to the ground on the sparsely protected climb

Unlike the continuous, splitter crack systems found in many trad areas, Eldorado’s cracks tend to form irregularly and intermittently. Although the hard sandstone lends itself to solid protection with both nuts and cams, the leader will en- counter a wide variety of placement types, including cracks, flakes, undercuts, and pockets. As a result, more skill and practice with gear placements are required. A look through the Eldorado guidebook or websites will reveal many climbs with PG-13 or R ratings, indicating difficult protection or serious run-outs. The newcomer to Eldo would be wise to start with better-protected G- or PG-rated climbs. Many Eldo routes climb past ledges, big and small, that present significant hazards in long falls. Care must be taken to protect early and frequently above these features to minimize the possibility of contacting a ledge. Fixed protection, including rusty pitons dating back to the 1950s or ’60s, should be backed up with a solid nut or cam whenever possible.

Like any crag, Eldorado has had its share of belay errors. These generally are not specific to traditional climbing, but certain issues may be raised by multi-pitch climbs. In 2015, for example, a climber following the second pitch of the Naked Edge (5.11) asked the leader to lower him a few feet after retrieving a stuck piece; the leader was belaying directly off the anchor in autoblock mode, and he accidentally caused the belay device to release the second’s weight, leading to a long fall.

In at least two documented instances, leaders strayed off-route onto more difficult and run-out terrain before falling. Some of Eldorado’s cliffs can present a maze of shallow corners and indistinct features, making close study of the guidebook and other resources essential. There also have been several reported cases of leaders failing to protect routes adequately for their seconds, causing them to take swinging and damaging falls. In one instance, the second climber on a traversing route cleaned all of the leader’s protection, leaving the third climber up the route vulnerable to a pendulum fall that ended with a broken leg.

Our review also included a number of unroped falls. Free soloing, unroped downclimbing, and scrambling add up to one of the largest causes of accidents in Eldorado Canyon State Park’s data. (Some of these victims were non-technical climbers who scrambled up the park’s easy-to-access cliffs.) It’s generally not pos- sible to say what might have caused these climbers to fall, but many popular Eldorado climbs require the use of suspect flakes or chockstones as holds, and these eventually come loose. Less dire but still a significant contributor to Eldorado injuries are bouldering falls. In the state park’s recent accident data, bouldering is listed among the top five accident types.

LOOSE ROCK

Although the good rock in Eldorado Canyon is firm, compact sandstone, many routes also pass through areas of loose or suspect rock. Eldo’s location in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains sees large seasonal temperature swings, freezing cycles, and occasional severe rain and hailstorms. These weather patterns combine to create increased risk from falling rock, especially after a recent storm.

Rocks often collect on ledges where they can be knocked off by climbers or storms. Some descent routes (notably along the West Ridge and the west side of Redgarden Wall) traverse ledges directly above popular climbs; rappel routes may lie above areas where climbers congregate. Many Eldo climbing routes pass directly through (or have belay stances on) various “rotten bands” of darker, highly fractured, and sharp sandstone. Great care is required in these ar- eas or wherever loose rock congregates. Leaders should test holds and flakes before pulling on them or placing gear behind them, and any climber should yell “ROCK!” loudly and repeatedly if something falls.

The falling rocks in our reports ranged from a few inches to “person size” and larger. (In 2002, a rock estimated to be 3x4x6 feet fell from the Bastille and exploded onto the road below, fortunately without hitting anyone.) Two incidents involved climbers walking at the base of cliffs. In one case, a broken hold struck the leader in the abdomen (causing a fall) and then continued downward to hit the belayer in the legs, forcing a rescue and helicopter evacuation. In 2002, a climber was traversing a rotten band on the fourth pitch of the popular Yellow Spur when he pulled off a loose rock that fell onto a finger and nearly severed it.

An analysis of incidents from 1998–2011 published by Rocky Mountain Rescue Group showed rockfall incidents in Eldo reaching their highest levels in spring and early summer, suggesting a correlation with the post-winter thaw. In our Accidents data, we saw concentrations of rockfall incidents in early summer but also in the fall and in February—it’s a year-round threat.

Natural and spontaneous rockfall is not uncommon in Eldorado Canyon (including occasional very large and destructive landslides); however, all but one of the rockfall reports in our records indicated that other climbers were confirmed or suspected to be overhead. People should avoid climbing or rappelling below other parties. Consider avoiding areas known for rockfall hazard (such as the Rewritten/Great Zot area of Redgarden or the upper West Ridge) on weekends.

Perhaps most obviously, wear a helmet. While a helmet is no match for a television-size block, it certainly can prevent or minimize injury from smaller debris. Note that many people only don their helmets once they begin climbing. The prudent Eldorado climber will wear one while belaying, hanging out below busy crags, or while hiking climbers’ trails below the cliffs.

STRANDING AND BENIGHTING

In our reports and in Eldorado Canyon’s data, getting stuck on or atop a climb is one of the most common incidents reported, frequently requiring rescues. All of this book’s reports of stranding (save one for which there was no route data) took place on Redgarden Wall, which has the park’s longest and most complex routes (up to 8 or 9 pitches) and descents. Some Redgarden routes top out along a good descent trail. But others require hard-to-follow rappel lines or a long, exposed descent along the East Slabs, where fourth-class terrain and an inobvious route make it easy to get stalled out the first time you do it. Rocky Mountain Rescue Group also has been called out to rescue several climbers stuck on Shirt Tail Peak, the highest summit in the park.

Half of the climbers who needed help descending were caught out after dark, many without headlamps. One stranding involved the inability of the party to hear each other. (Wind and the roar from South Boulder Creek can make communication difficult between leader and followers.) The belayer tied off his climber and went to get help; eventually, a rescue team was able to rappel to the stuck climber and help him descend.

Fortunately, despite the frequent need for rescue, no injuries were reported among the stranding incidents. In one case, a party was able to self-rescue but not before spending a chilly March night out in T-shirts; they concluded, “It was a pretty miserable experience.”

The main strategy to avoid stranding is adequate preparation. Climbers should thoroughly research descent routes from the major cliffs, carry a description copied from the guidebook or online sources, and familiarize themselves with backup descents in case plans change during the day. An early start on long routes is crucial to allow time to complete an unfamiliar climb or descent. Always toss a headlamp in the pack or clip one to the back of your harness as an additional measure of insurance.

LOWERING AND RAPPELLING

A crop of incidents in recent years—all involving injury or fatality—indicate that climbers are making costly mistakes when lowering their partners in Eldorado. In four incidents reported in Accidents, the end of the climbing rope slipped through the belay device because the rope was not long enough to return the lowering climber to the ground. In two others, there was a miscommunication and a leader fell after leaning back from an anchor, thinking he or she would be lowered.

Such incidents are hardly unique to Eldorado Canyon or to traditional climbing areas—indeed they have become increasingly common in the sport climbing and gym era. It’s possible that some newcomers to Eldorado have an expectation that anchors will be set at heights convenient for lowering with a single rope. In fact, however, most Eldorado anchors are set irrespective of their height above the ground, using available trees or ledges. In other words, these were never intended to be lowering anchors.

As a result, climbers must study the guidebook or obtain other beta to ensure their rope length is adequate to lower a leader. In certain cases, a two-rope rappel will be the only way to descend from a single-pitch climb. Other anchors may allow lowering, but only to a ledge above the ground, from which downclimbing will be required. As a precaution, belayers should always close the system by tying in to their end of the rope or knotting the free end, either of which will prevent the rope from being fed through the belay device while lowering.

As with lowering, the types of rappelling accidents seen in Eldorado Canyon are not unique to the area. Reports show two main causes: anchor failure and rappelling off the end of the rope. In one of the anchor failures, climbers were prac- ticing rappels when a sling appears to have disconnected from a locking carabiner. In another case, a single-point anchor failed when the second climber leaned back to rappel. In several cases, climbers rappelled off the ends of their ropes.

Climbers should study route descriptions to ensure they have adequate length ropes (or if two ropes are needed) for rappels. Anchors should be checked carefully. Although many rappel anchors in Eldorado now are equipped with modern bolts, many others rely on slings around trees or blocks. Don’t hesitate to replace faded or damaged slings; make sure trees are at least five inches thick, well-rooted, and healthy; test blocks or chockstones to ensure they are solid. Backing up rappels with a “third hand” (friction hitch) and tying knots in the end of the rope should be standard procedure on any Eldo rappel.

DEGREE OF DIFFICULTY

Eldorado Canyon has many excellent climbs in the lower to middle grades, and unsurprisingly these are both very popular and also the scene of many accidents. When the state park looked at its accident records, it found that about two-thirds of Eldorado’s climbing accidents involved routes 5.8 or easier.

That said, our review of reports in Accidents in North American Climbing shows a distribution of incidents throughout Eldo’s range of difficulty. (With one exception, the Eldorado reports in this year’s edition involve climbs rated 5.10 or harder.) Though conventional wisdom suggests that Eldo’s sandbagged “moderates” pick off a disproportionate number of novices, it’s clear that the ability to climb harder grades will not protect you.

The best advice for safer climbing in Eldo holds true for many similar areas: Arrive equipped with appropriate gear and prepared with solid fundamentals for placing protection, belaying, and rappelling. For climbs involving more than one pitch, study the route up and the way down, and make a plan to retreat if necessary. Be realistic about your abilities and flexible in response to conditions, and you’ll enjoy one of the nation’s highest concentrations of quality traditional climbs.

Joel Peach is a contributing editor of this publication. Thanks to Steve Muehlhauser, Mike McHugh, Alison Sheets, and Rocky Mountain Rescue Group for their help with this article. Previous “Danger Zones” articles have analyzed the accident histories of Mt. Rainier, the Nose of El Capitan, and the Exum Ridge on the Grand Teton.