Ryu-Shin: Return to the Mirror Wall

Greenland, East Greenland, Renland

It had been a 50-day odyssey to get from Oban, Scotland, to the massive shield of granite called Mirror Wall on the Renland peninsula of East Greenland. Those seven weeks included sailing through rough seas, vomiting with seasickness, dodging storms in the Faroe Islands and Iceland, lots of hangboarding, waiting for the sea ice on Greenland’s east coast to clear up, ice-floe slaloming, and, finally, 12 days of ferrying heavy loads over 19 miles of endless moraines and treacherous glaciers to reach the wall.

On August 6, 2023, three tiny specks—the American climber-photographer Ben Ditto, the bold British headpointer Franco Cookson, and I—stood on the crevasse-sewn Edward Bailey Glacier, getting our first look at the cold, impenetrable, northwest-facing mirror. Our hearts sank. Though two routes had been established on the wall’s flanks and one in left-center, our plan was to find a free line directly up the center of the 1,000-meter wall. However, it seemed completely blank, with no obvious features and no clear possibilities for natural protection.

Our options were either to repeat one of the three existing lines or to try a different, easier mountain. But Mirror Wall is by far the biggest, steepest, most eye-catching rock face in that region. And we weren’t here to climb a sure thing.

As the sun slowly emerged from behind the wall, a line of abstract shadows suddenly appeared, suggesting flakes and seams and igniting a spark of excitement. “We don’t need to succeed,” I said. “We just need to try our best!”

Just before we committed, our fourth teammate, Nicolas Favresse, rejoined the team. During our first day of hiking loads, a big granite block had slid from under Nico’s foot; he fell into a pool of icy water and deeply gashed his upper shin. To avoid infection, he’d been forced to stay on the sailboat, rest, and keep his wound clean while the three of us continued to ferry loads.

Once on the wall, we spent nine days slowly fighting our way up a mix of hard free climbing, long, committing runouts, and precarious aid on skyhooks and birdbeaks. Most days, we were on the verge of bailing. About halfway up, we reached a right-facing dihedral, one of the few distinct features on the wall’s lower half. The corner, however, was completely closed, with no possibilities for pitons, beaks, or even copperheads; plus, the rock was flaky, exfoliating, and sandy.

Using friction with my palms and feet, I pushed my way up the corner for about 20 meters, placing the odd piece of marginal gear. Finally, with no more possibility for protection, I carefully set a hook on a micro-edge and hand-drilled a bolt. Four meters higher, out to the right, I could see a flake that clearly would take a cam.

Up I went, pushing the two walls apart, the gritty rock crackling under my feet, swimming deeper and deeper into a dark sea of uncertainty. However, no matter how hard I tried, I just couldn’t reach that flake. At one point I even stayed in the corner and climbed past the flake—but with nothing to aim for, I had to take the ten-meter fall. For two days I tried this section, taking frightening fall after frightening fall. On one, I hyperextended my right foot, leaving my ankle swollen and blue.

Above us, an obvious crack system looked to lead to the summit. But I was unable to free climb to it, and we’d run out of aid tricks. Additionally, we were slowly running out of food, time, and—more importantly—toilet paper.

Maybe if I aided up high on the bolt and placed another bolt, I could reach the flake. But where, I pondered, should one draw the line? Even the blankest of walls can be climbed with a bolt ladder. Before starting up, we knew we would have to place bolts, but we had agreed there had to be a certain distance between them, requiring either free climbing or hard aid to bridge the gap. Maybe this call is rather subjective—very dependent on skill, strength, and courage. But you must draw a line if you want to keep the challenge alive.

As we retreated, gutted, I started making plans to return.

Nico, Ben, and Franco made other plans for 2024, so I had to find a new team. The Wide Boyz crack expert Pete Whittaker came to mind—he’s just handsome enough that his reflection on the smooth granite meant we wouldn’t be looking at ugly stuff! “I’m not sure if it will go—there is a possibility that we make it to the 2023 high point and have to bail again. But I need to go back to find out,” I told Pete over the phone in February. One year earlier, we had spent a fun month together in Patagonia, managing a couple of first free ascents.

“Well, if there wasn’t uncertainty, it wouldn’t be an expedition, would it?” Pete said.

It felt like a stroke of genius when I thought of inviting the Japanese trad-master Keita Kurakami, with whom I’d bonded at Camp 4 in Yosemite through our shared enjoyment of playing the flute. With his rope-solo free climb of the Nose of El Capitan in 2018 and his many committing trad climbs, he’d always inspired me with his philosophical approach and loyalty to style. When I warned him of the magnitude of the challenge, he humbly said, “It sounds like the wall that will test a human’s mental strength. I’m really looking forward to it!” Meanwhile, the French climber-photographer Julia Cassou, who had joined Pete and me on some of our climbs in Patagonia, decided she couldn’t miss out either.

And then we received a devastating blow, just two weeks before the expedition—a shocking, three-word message from Keita’s friend Takemi Suzuki, who’d been slated to join as the team photographer: “Keita has passed.” I hoped it was just a translation mistake, but tragically we learned that Keita, while hiking on Mt. Fuji to train for Greenland, had died when his heart stopped, the result of an underlying heart condition. He was only 38.

Understandably, Takemi could not join this trip. After a few days of contemplating, Pete, Julia, and I decided to continue, and we strengthened the team with the experienced El Cap aid climber Seán Warren from the U.K., who, on very short notice, managed to get the green light from his boss and girlfriend (not the same person). We laminated a photo of Keita to carry with us, a close-up portrait by Drew Smith, Keita’s broad smile radiating happiness. Even though he was gone, Keita would be coming with us in print and in spirit. If we managed to carry this snapshot all the way up the wall for a summit picture, it would surely bring a smile to Keita’s close friends and family.

On July 29, we set out on the sailboat Cornelia from Ísafjörður, Iceland. In charge was Captain Mike Brooks from the United Kingdom and the first mate, Trevor Green, from Canada. On August 2, we lowered anchor in Skillebugt Fjord, the drop-off point for Mirror Wall. We got straight to business ferrying loads and managed to get all the gear and food to advanced base camp, on the glacier about three hours from the wall, in only seven days. Our pickup was arranged for September 5, aboard the sailing vessel Caval’ou, skippered by Vicente Soto.

I had raved to my teammates about the famous “Arctic high,” and how the previous year we had only had two days of rain during our 30-day stay. But there would be no such luck this time: It ended up being overcast with at least some rain or snow on most days. We only had two days of pure blue skies on the whole trip.

Starting up the wall in wet conditions, Pete and I made quick work of the relatively easy first 300 meters. The next day, August 12, we hauled gear and food, committing to a push that would go on for 18 days. We took advantage of every little weather window to advance toward the dihedral, last year’s high point, 600 meters up. Seán Warren, with the agility of a cat, took care of the difficult aid, sometimes on wet, snowy rock.

“I never knew aid climbing could be so graceful!” Julia exclaimed, pointing her lens.

“You are a pretty good aid climber for a free climber!” Seán W shouted down as he repeated some of my delicate hooking from the previous year.

Pete stepped up for the hard, run-out free sections. On pitch nine, I was attentively belaying as Pete delicately tick-tacked up small edges ten meters above his last piece. All of a sudden, he let out a scream as a crimper crumbled under his fingers. I saw him sagging backward, almost falling, and my heart skipped a beat. Somehow, clinging with just two fingers, Pete reached out to a good hold.

“That was close!” he said.

As Seán W and Pete took most of the hard leads, I shouted up beta, while Julia took care of the photos and rope management. It was all part of Pete’s master plan: “Let Seán W and I do the leading,” he told me. “Then, when we get to the dihedral, you will be fresh for the rematch!”

On day seven, August 18, we reached pitch 13, the notorious corner.

I was curious: Was it really impossible, like it had felt a year ago? Would anything be different this time? I prepared to just give it my best, without any attachment to the outcome. If I tried my hardest, I could accept failure without regrets.

“I’m just going to take a look,” I said.

“Yes. Just ease into it,” Pete coached. “Take a few falls, slowly build up your confidence, and then smash it out!”

Julia and Seán W watched from below as the silent air filled with shared excitement. I thought of Keita, and how he would have loved to be here; I thought about how life is fragile, and how it can be taken at any moment. I put Keita’s photo in my chest pocket, feeling it give me strength.

Back in the corner, I moved with precision, my feet confidently smearing, my palms pushing on the nothingness. There I was, far above the bolt, that old, familiar place. I had visualized this moment so many times over the past year. I looked to my right: The flake was within reach! I couldn’t believe it. I threw in a cam and gently shifted my weight onto it. A hollow cracking sound reverberated as the flake expanded. A fall from here, with the bolt five meters below and to the left, could create an ugly swing into the dihedral—but the flake held. I continued up with a mix of aid and free climbing, finally reaching better rock and protection.

“It goes, boys and girl!” I hollered. We all cheered in joy.

A steep but featured black basalt dike brought me to a vertical face without protection, where I placed a bolt for an anchor. The next 30 meters looked like intricate aid on flakes and seams. So I called up Seán W, speculating it was probably the last section where he could make his aid skills shine. Fortunately, the wall was at its steepest, as Seán put a few big holes in the air. “I haven’t taken this many falls on any of the hard aid on El Cap,” he shared. Eventually, he reached the promising crack system that looked to stretch clear to the summit.

The next 30 meters were a seam on which Seán W made his funny birds sing. I named this pitch the “Magic Salathé Flame,” since it looks like the single-pitch trad line Magic Line (Vernal Falls, Yosemite), but with the exposure of the Salathé headwall (El Capitan), in an alpine setting similar to Eternal Flame (Trango Tower, Pakistan). The seam turned into a finger crack, and Pete and I started switching leads, free climbing pitch after pitch of spectacular, quality cracks, high on the headwall of Mirror Wall. As we drifted in this ocean of granite, the views broadened and the tip of the ice cap appeared behind the surrounding peaks; the glacier below now seemed very distant.

One evening, as I was sorting out the anchor before zipping down the fixed lines to our portaledges, the photo of Keita fell out of my pocket. It hung for a second, floating in an updraft, before I quickly grabbed it and put it back into my pocket.

“We still need you!” I said.

On August 22, day ten on the route, we committed to a summit push. Taking the sharp end, Julia delicately weaved her way up, dodging ice and snow, until she liberated us with a cry of “SUMMIT!” After some big, emotional hugs, I pulled out the photograph of Keita for the group picture. We sat on the summit couch, our feet dangling over 1,000 meters of air, enjoying the view of the endless ice cap and basking in a rare bit of sunshine.

The next day, back at our portaledges, we finally took a much-needed rest day. I was reading in the portaledge when shutterbug Julia, hanging on a rope above, asked me to stick out my head for a picture. Reluctantly, I sat up. As I fumbled through the ledge opening, the photograph of Keita, which I’d been using as a bookmark, fell out. It started to spin extraordinarily fast as it floated in the breeze, giving the photo a flickering effect, Keita just smiling his big, infectious smile. Then, almost as if to say he was no longer needed, Keita flickered away from us.

As Keita wrote in his story “A Thousand Days of Lapis Lazuli” in Alpinist 56, “The rock we climb is a mirror, and in it, we see the silent reflections of dialogues that have taken place between climbers across many decades—and also within ourselves. Out of all this action and conversation, something greater emerges that is transmitted from generation to generation, forming a kind of collective intelligence, an influence that might still flicker across great spans of time and space, mere fragments of dreams of the billions of lives that come into the world—and leave the world.”

During his life, Keita had the shakuhachi flute player’s name of Ryu-shin, which translates to “Heart of the Dragon.” This climb is named in his memory.

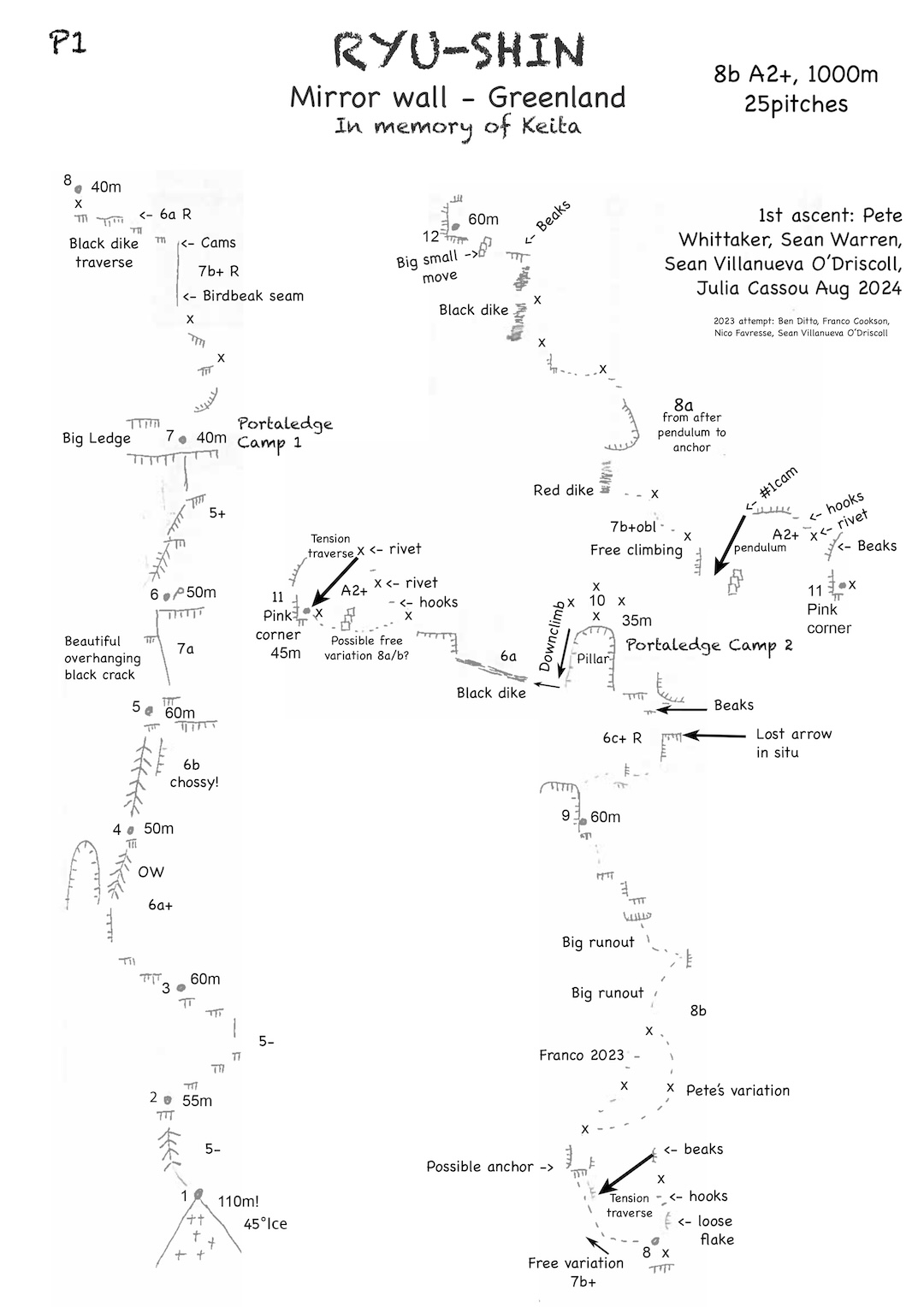

SUMMARY: First ascent of Ryu-Shin (1,000m, 8b R A2+) on the northwest-facing Mirror Wall, Renland, East Greenland, by Julia Cassou, Seán Villanueva O’Driscoll, Seán Warren, and Pete Whittaker, August 11–29, 2024. They reached the summit on August 22.

During the descent, the team stayed on the wall for seven additional days, aiming to redpoint various pitches that had not gone free during the first ascent. These included the run-out “razor blade slab” of pitch nine (Whittaker, 8b R); pitches eight and ten, leading to the second portaledge camp (Warren, 7b+ R and 6c+ R, respectively); the pitch 13 dihedral (Villanueva O’Driscoll, 7c+ R); and the pitch 16 finger crack (Whittaker, 7b+). A detailed topo of the route is at the AAJ website.

Villanueva O’Driscoll writes: “I tried my hand at the Magic Salathé Flame, pitch 15, laybacking the thin, offset seam above the wildest exposure possible, my feet smearing, every move feeling nails and low percentage. In the end, we managed to free all but that pitch and pitches 11, 12, and 14. I do think these four pitches will someday go, providing a spectacular free wall. But for us, with the time we had left, they were just way too difficult.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Seán Villanueva O’Driscoll was born and raised in Belgium, with Irish-Spanish roots. He has been climbing challenging big walls in ranges around the world for the past 20 years.