Up, Up and Away: The First Ascent of Yashkuk Sar I

Pakistan, Karakoram, Batura Muztagh

Crashhhh! rang through the perfectly still night.

To say this woke up August Franzen, Cody Winckler, and me would be a lie: How could we sleep? We were camped below the biggest objective of our lives, on our first trip to Pakistan, alone in the Yashkuk Yaz valley aside from our two cooks and a liaison officer back at base camp, surrounded by the most beautiful, terrifying, inspiring, and chaotic mountains we’d ever seen. Now, on the glacier beneath Yashkuk Sar I (6,667m), about a mile past our advanced base camp, I poked my head out the tent door to see a gargantuan avalanche roaring down the peak’s north wall, its powder cloud billowing toward us.

“Should we run?” asked August.

“I think we’re good—there’s no way any chunks can make it over that moraine,” I replied.

I watched, mesmerized, as the powder cloud grew taller, closer, taller, closer, then I zipped the door shut in the nick of time. The maelstrom rocked our tent, and we all sat up to brace the poles against the wind and driving snow. When the blast finally subsided, we shook the snow from the tent, unzipped the door, and looked back out to see Yashkuk, silent and brooding again, its seracs and ice walls glistening under the full moon.

A month earlier, on August 16, I’d sat at the Jones Social bar in the Hamad International Airport in Doha, Qatar. To my right sat Cody. He had moved to my hometown of Cody, Wyoming, a couple of years earlier, and we had been primary climbing partners ever since. To Cody’s right sat August, with whom, aside from five quick minutes on the Kahiltna Glacier that spring—him half hidden under a parka and glacier glasses—I had never spent any time. I’d heard August’s story from friends, and it was one filled with tragedy: His girlfriend, Kalley Rittman, had passed away in a climbing accident near his home in Valdez, Alaska, four years earlier, and he had lost a string of other close friends in the year that followed.

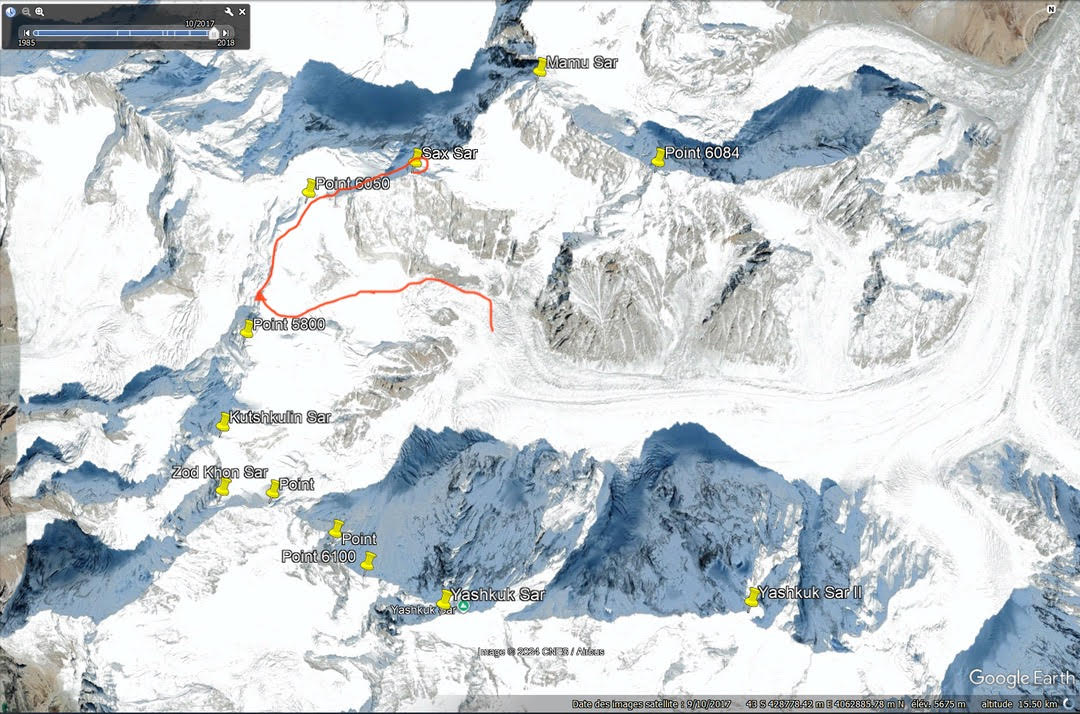

Our trip had come about from a shared desire to fulfill a lifetime dream: to climb in the Karakoram, the greatest mountains on Earth in all of our eyes. I had stumbled upon Yashkuk Sar on Google Earth a year earlier, while perusing the more remote reaches of the Karakoram, and it seemed the perfect objective: unclimbed, minimally explored, high enough but not too high, hard enough but (hopefully) not too hard, with an aesthetic and objectively safe line up and then a logical way to traverse the mountain and descend a different route, adding to the adventure. We each ordered a Tiger beer and clinked bottles beneath a mirror inscribed with “Up, Up, and Away,” toasting the trip to come.

On August 18, together with our liaison officer, Khan Zada, and our trip organizer, Ali Saltoro, we stepped down onto the tarmac in Skardu. We were picked up by one of Ali’s jeeps, and after meeting our cooks, Ali and Idrees, along with another jeep filled with base camp supplies, we set off along the Karakoram Highway.

In the afternoon of our second day on the road, we turned into the Chapursan Valley. The farther we drove, the more it seemed we went back in time. As we passed rows of mudstone houses, terraced wheat fields lined with poplars, and free-roaming sheep and yaks, it was easy to imagine we were back in the days when, per the local lore, Genghis Khan rode in over a pass to the north, or when weary travelers carried silk through the valley on the backs of camels. Only the occasional car or motorbike disrupted the illusion.

Our destination was the Pamir Serai, a guesthouse owned by a bearlike, blue-eyed, stony-faced man named Alam Jan, whose booming laugh and stories of mountain adventures filled our last evening in civilization. The next morning, we started our walk toward base camp, heading southwest along the Yashkuk Yaz Glacier. Two mellow days of hiking with our 25 porters and one donkey would bring us, along with Ali, Idrees, and Khan Zada, to base camp at 4,000 meters, eight miles up the glacier.

To the best of our knowledge, only three climbing teams had visited this valley, about ten miles from the border with Afghanistan, and the most recent had been 18 years earlier. The first two teams— one Japanese (2001) and one Russian (2005)—had aspirations to climb Yashkuk Sar I, as we learned from the locals later. But no one had made significant progress up its imposing north wall, which is split by a 2,000-meter central buttress that we hoped to climb. In 2006, Markus Walter and Bruce Normand, who’d shared valuable information with us before we left, climbed three of the lower 6,000-meter peaks in the valley after bailing from an attempt on nearby Batura II.

After one night in base camp, we established advanced base a mile up the west fork of the Yashkuk Yaz, beneath the noisy north wall of unclimbed Yashkuk Sar II, the lower, eastern summit of the twin-peaked Yashkuk massif. Fortunately, there were huge mounds of rocky rubble on the glacier to shield us from its rumblings. The next morning, we got our first close-up view of our peak.

Plastered with fresh snow and with the summit veiled by clouds, the north wall was intimidating, though the central buttress looked safe. The mist-cloaked upper headwall was still a big question mark. It was only on the first of our acclimatization climbs—a 5,300-meter subpeak of the 6,000er across from Yashkuk II—that we finally glimpsed the upper slopes. The headwall looked hard, but discontinuous white streaks up its center gave us hope there would be dots to connect. On our second warm-up climb, of the 6,200-meter Sax Sar, via a new route that spiraled up the mountain from its southeast corner, we were rewarded with a perfect view of Yashkuk Sar I’s north wall, framed by a sea of jagged peaks. We were floating in the sky, higher than we’d ever been, in the heart of Central Asia. Our objective was beautiful; our bodies were ready.

The alarm rang at 3 a.m. on September 19, just three hours after we’d witnessed the massive avalanche on Yashkuk Sar I. We dusted the snow off our bags, packed up, and set off across the glacier. The avalanche had been intense, but it wasn’t the first we’d seen off Yashkuk, and it wasn’t particularly concerning: The central buttress’s 2,000 meters of gray ice and black stone protruded from the serac-crowned wall, protecting us, we assumed, from the monstrous avalanches that regularly swept the face.

By noon, we had already finished our daily goal of 500 vertical meters. August had led two long simul-blocks—up an initial ice couloir and then left, across broken gneiss veiled by deep powder, to reach a system of ice runnels that bypassed the monolithic lower buttress. The big snowfield above had just gone into the shade, so up, up, and away we continued.

Across the snowfield we gained a broad couloir, just left of the buttress crest, that glistened with ancient blue ice. Partway up the couloir, at around 5,600 meters, with the shadows lengthening, we looked for a place to spend the night.

“What about that snow arête?” I asked, pointing left when Cody and August arrived at my belay. “We’ll be safe from anything that falls, and it doesn’t look too hard to get to—just eight meters across that bit of rock.”

An hour and a half later, I laughed sardonically at my words as I desperately brushed snow aside in search of the tiniest ripple for my frontpoint in the black gneiss. The last 20 meters—not eight—had offered a distressing combination of loose yet compact slab traversing, hammering in beaks, and stuffing cams behind frozen blocks. Now my calves were on fire, though I was just a body length from good ice. Finally, I unveiled a slanting edge, just enough to rock up and left and reach the ice.

As the sun set, we began to arrange our first bivy. After a strenuous hour of trying to hack a flat spot out of the arête, we broke out our secret weapon: a Russian ice hammock. After another hour and a half of faffing, chopping, tensioning, and swearing, the tent was pitched, with only six inches hanging over the ledge. Inside its green walls, we set about making water, eating, and trying in vain to sleep.

At dawn, I was stirred by a crash and a hiss. I looked out the tent door to see an immense avalanche roaring down the northeast face a couple of hundred meters away, the billowing snow illuminated pink as it raced down to the glacier 1,000 meters below. Safe on our ice arête and pleased with the previous day’s progress, we packed up leisurely in the warm morning sun, then set off up interminable ice slopes.

Cody led that day—up, to the right, up more, then back left, on calf-burning, lung-searing, steely-blue ice. As the sun sank toward the peaks of the Hindu Kush, he traversed to a ridge festooned with bulging snow mushrooms.

“This isn’t gonna work for a bivy!” he called back from the first, innocent-looking (from our perspective) mushroom. “I don’t know what’s holding this thing on, and there’s an overhanging wall on the other side!”

“What about higher?” I called back. “I’m sure we can get the tent up on one of those mushrooms! And isn’t there a traverse ledge on the other side?” I recalled spotting a white line that cut left across the arête to an ice gully, but I wasn’t sure Cody was near it.

“I don’t know, dude—it’s pretty wild over here! I could bring you guys over.”

“Is there a good anchor?”

“Ummmm…”

As we deliberated, I felt a primal fear of the impending darkness. This had been the “surefire good bivy,” and if the whole arête was as marginal as Cody’s stance, we were in for a rough night.

Cody investigated higher. The next mushroom was equally precarious, but then he spotted one just below it that might work. He climbed off the back side of the higher mushroom, lassoing it and adding some screws for a belay.

It was a wild spot, a blade of snow perched at around 5,900 meters, directly below the headwall we’d spent nearly a year fretting about. Bounded by rocky arêtes, the headwall looked steep, but it was well protected by those arêtes from the looming seracs on either side. Our best way through, we figured, would be an icy dihedral splitting the wall.

After many brews and a dinner of ramen thick with life-sustaining peanut butter, we crawled into our shared sleeping bag. Not ten minutes later, we heard another crash: Not to worry, I thought. It must be from one of the seracs to our left. We almost didn’t bother to look, but when Cody unzipped the door, we were horrified to see a huge avalanche, lit by the full moon, roaring down the dihedral we intended to climb the next day, though well to the left of our knife-edge bivy. A big mushroom must have collapsed, and dozens more like it threatened our line.

Our world turned upside down: I knew we couldn’t climb up that deadly corner. Failure seemed imminent.

“Well, what do you guys think?” I asked into the gloom. Awkward silence.

I frantically scrolled through photos of the headwall on my phone, comparing angles and features. The center line was clearly out, and the monolithic rock towers crowning the western edge of the headwall, to our right, looked too hard. But maybe there, on the left edge of the wall, a couple of hundred meters from the dihedral, was a way. Through a rock band, up an ice arête, then up a chimney that cut through another rock band below a wild mushroom ridge. We all agreed it was worth a shot.

At dawn, after a left-diagonaling rappel off the ridge, August led a long block up the ice arête, toiling through deep snow in the hot sun. By early afternoon, we had reached the headwall. It was time to answer all those questions.

The first rope length—my lead—was tenuous: A compact slab of jet-black gneiss with little for hooks or protection led to a thin dribble of delaminated ice. After a few body lengths of delicate tip-tapping, I stepped left, onto a hanging snow arête, aiming for a vertical, snow-plastered rock band. Shattered but well-frozen gneiss made for good hooks, abundant gear, and quick progress.

“Rock!” I yelled as one of my ropes dislodged the unfrozen block I’d just worked so carefully to avoid. “Rock...ROCK...ROCK!!!”

Defying the logical fall line, the block was somehow skipping toward the arête where August and Cody were belaying, exposed and vulnerable, a solid vertical mile above the glacier. A white poof of down shot into the air as the rock hit Cody’s right shoulder.

“ARE YOU OKAY?!” I screamed.

“Yeah...I’m...good,” he grunted.

I continued, this time more gingerly. Half an hour later, I had a five-piece rock anchor and stood on an outrageous snow mushroom on a knifeblade arête where we could maybe, just maybe, pitch the tent. I brought up August and Cody, and as the sun set, we settled into the airiest bivy of our lives. While a good six inches of tent hung off each side of the arête, the inside of our little green haven felt safe enough—until you shifted and felt the void beneath a cheek. The altitude here at 6,200 meters was killing our energy and appetite.

On the morning of September 22, we didn’t bother with breakfast. After coffee and a couple of rounds of electrolytes, Cody traversed back onto broken gneiss as the moon set and the sun rose. A rope length higher, we were back in the shade of the cold headwall. Cody fought through a heavy blanket of snow as he scratched up the rock beneath. I glanced nervously between the three-beak anchor, the dizzying exposure beneath the mushroom on which we stood, and Cody as he dug sideways, beneath a cornice, trying to regain the crest.

The next pitch climbed the rocky arête itself, across which Cody eventually traversed right and out of sight below a mushroom. For the next half hour, the rope inched out slowly and snow poured down. Seconding, I saw what had taken so long: Around the corner, the wall overhung slightly, with the whole north face sweeping below, while hooks and protection came solely in the form of questionable, jutting blocks. When we arrived at the belay, Cody still looked exhausted from his lead.

I continued up and right, weaving through the most surreal snow features I’d ever seen—otherworldly, Dr. Seussian blobs. “We’ve gotta be almost there—I bet that was the last hard pitch,” August said when he reached the belay. I chuckled at his optimism as I set off toward more cartoonish mushrooms and an alabaster band of marble capping the headwall. While trying to get over a mushroomed arête, I heard a whoompf and felt my right foot drop. I watched the mushroom accelerate silently, then cascade over the headwall with a crash.

“Okay, I think that was the last hard one,” August repeated at the next belay. The ice runnel above didn’t look bad, but something told me this was deceiving, and soon I found myself stemmed wide and clearing out pockets of snow from overhanging, honeycombed ice. I sliced through the cornice topping the runnel, certain I’d poke through to sunlight on the summit ridge, only to find more shade, blue ice, and another cornice.

“That has to be the ridge up there,” we all agreed at the next belay, pointing to the skyline. I pulled through the next cornice. Still in the shade. Finally, half a rope length of trenching through snow deeper than myself brought me into the light.

The imagined joyful victory stroll across the summit ridge was anything but. Our lungs screamed as we trudged through knee-deep snow, illuminated gold by the setting sun, while a bitter west wind stung our faces. Our plan had been to sleep on the summit, but halfway up the windswept ridge we dashed into a wide crevasse. While it proved more of a wind funnel than a wind block, we were thrilled to finally have somewhere flat to bivy.

We awoke from our half-sleep to an inch of snow covering everything inside the tent. It had accumulated overnight from the tiny breathing hole we’d left in the door. The mood was grim as we brewed up and choked down a few bites of whatever we could stomach: half a Clif Bar for me, a Gu packet for August, and, in classic Cody fashion, a sugary drink for him.

It had been a rough night and everything was wet, but we knew the summit was close. If we were lucky, we’d be off the mountain that day.

As the sun rose, we left the tent with only parkas and water bottles in our packs. After 30 minutes of walking—and four days on the wall—we could go no higher. We hugged, cheered, and marveled at the incredible view, surrounded by four of the greatest mountain ranges on Earth (the Karakoram, the Himalaya, the Hindu Kush, and the Pamirs) spread across four countries (Afghanistan, Pakistan, China, and Tajikistan). Then we dropped a couple of meters off the east side of the summit to a flat, wind-sheltered plateau that would have made a perfect bivy. Oops.

From his pack, August produced a little Ziploc bag filled with some of Kalley’s ashes. Cody and I each laid a hand on his shoulder as he threw the ashes up into the wind, which swept them across the Karakoram toward China. We stood silently as August let the tears flow, then we sat, taking it all in, beneath a deep-blue sky.

An hour later, we collected our gear from the crevasse bivouac, crossed the hanging glacier below the summit pyramid, and began rappelling the broad ice gully splitting the mountain’s west face. Some 600 meters lower, we tied back in and traversed up and left to where we could cross the west ridge and drop back down toward the West Yashkuk Glacier cirque. One thousand meters passed in a blur of Abalakovs and downclimbing; that evening, we made our final rappel over the bergschrund. Our hackles stayed up as we weaved through the gaping crevasses of the upper glacier basin, giving wide berth to seracs over its western edge.

Before the sun set on September 23, we crossed beneath the final debris field and coiled the rope, safe on the rocky, dry glacier. At the first stream on the bare ice, we knelt to suck thirstily at the trickle, savoring the sweetness of the water.

Three weeks later, the three of us sat again beneath the “Up, Up, and Away” mirror in the Qatar airport bar, clinking three Tiger bottles together to celebrate two incredible months in Pakistan. We named our climb Tiger Lily Buttress, inspired by the Tiger Team moniker that our exuberant cook, Idrees, had given us at base camp upon our successful return. The trip wouldn’t have been the same without Idrees’s “Tiger Style,” and after our ascent of Yashkuk Sar I, none of us would be, either.

SUMMARY: First ascent of Yashkuk Sar I (6,667m) in the northern Batura Muztagh of the Karakoram, Pakistan, by August Franzen, Dane Steadman, and Cody Winckler (all USA), September 19–23, 2024. The trio climbed the mountain’s north pillar and named it Tiger Lily Buttress (2,000m, AI5+ M6 A0). They descended by the upper west and lower north faces.

During acclimatization, they also climbed a new route on Sax Sar (ca 6,200m). Their route spiraled around the mountain, starting on the south side and following a glacial basin westward to eventually gain the west ridge, where they bivouacked. They followed the ridge over a glaciated dome then traversed a glacier below the north face summit pyramid to snow slopes leading to the east ridge, which they followed to the top. They did not name their route. Sax Sar had previously been climbed, in 1999, from the Kutshkulin Glacier on the opposite side; see AAJ 2000.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Born and raised in Phoenix, Dane Steadman now calls Cody, Wyoming, his home. Between expeditions, he works as a guide and field tester.