Langtang Lirung, East Face

Nepal, Langtang Himal

The dramatic events of the days on Langtang Lirung are deeply etched in my memory. They belong to the wildest and most beautiful I have ever experienced in the mountains, but also the most painful.

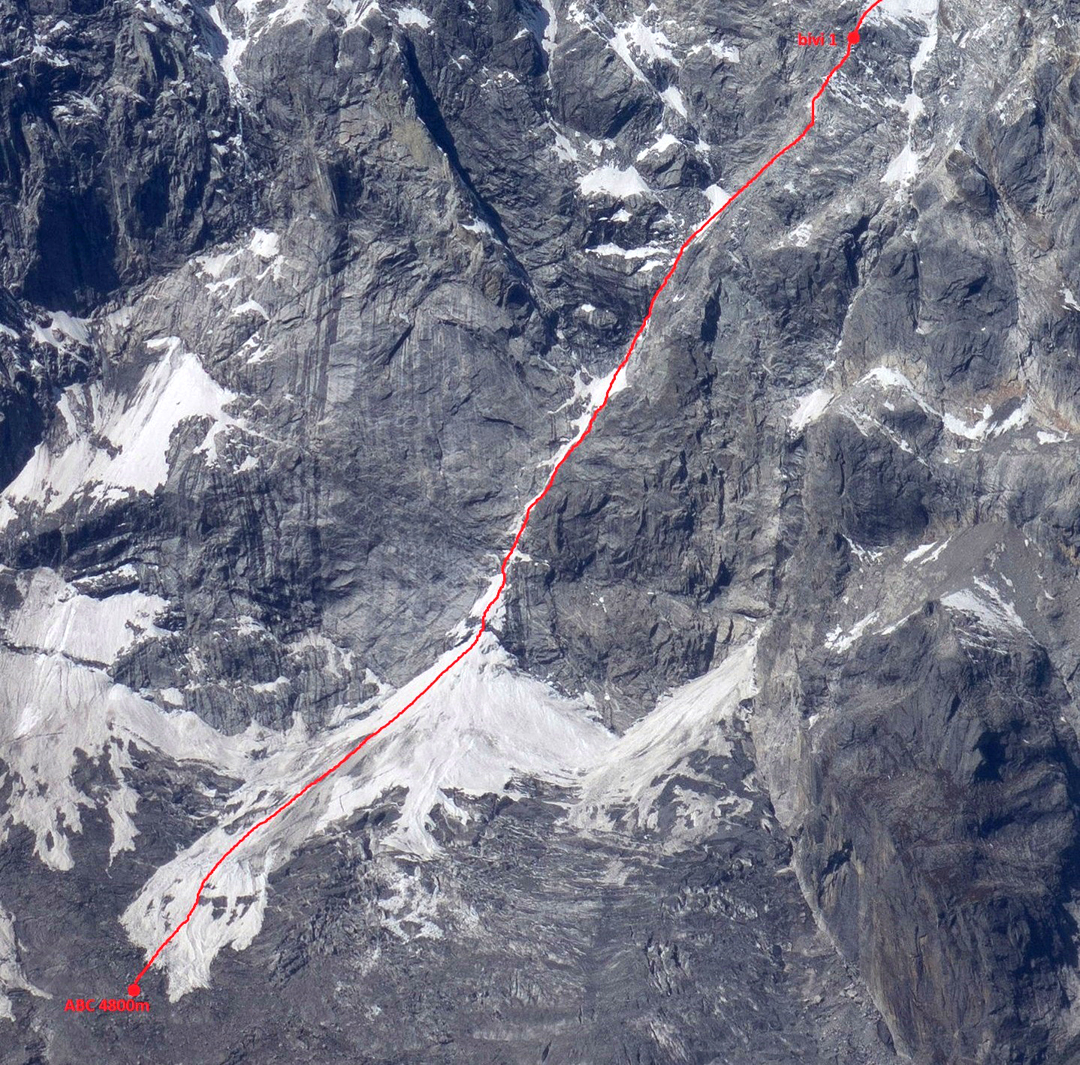

Our small team arrived in Kathmandu in September and spent the initial days hanging around bars, as heavy rain blocked access roads. Once the roads were cleared, we trekked to Langtang via Gosaikunda and climbed Naya Kanga (5,863m) for acclimatization. On October 7, three weeks after arriving in Nepal, we set up base camp south of the Lirung Glacier at 4,500m, in sight of the huge, unclimbed east face of Langtang Lirung (7,227m).

On October 20, Ondrej (Ondra) Húserka (Slovakia), Ondrej Mrklovský (Czech Republic), and I made our first attempt, starting from a camp below the east face at 4,700m. When the sun rose, a warm breeze started to blow, and the effect was immediate. As if someone had opened a huge tank above us, stones and ice began to fall and we heard sounds like the growling of an angry dog. For 24 hours, we cowered under a small rock overhang while avalanches flew over our heads. After we reached base camp, Ondrej Mrklovský said calmly, “Mara, I’m not going up there again.”

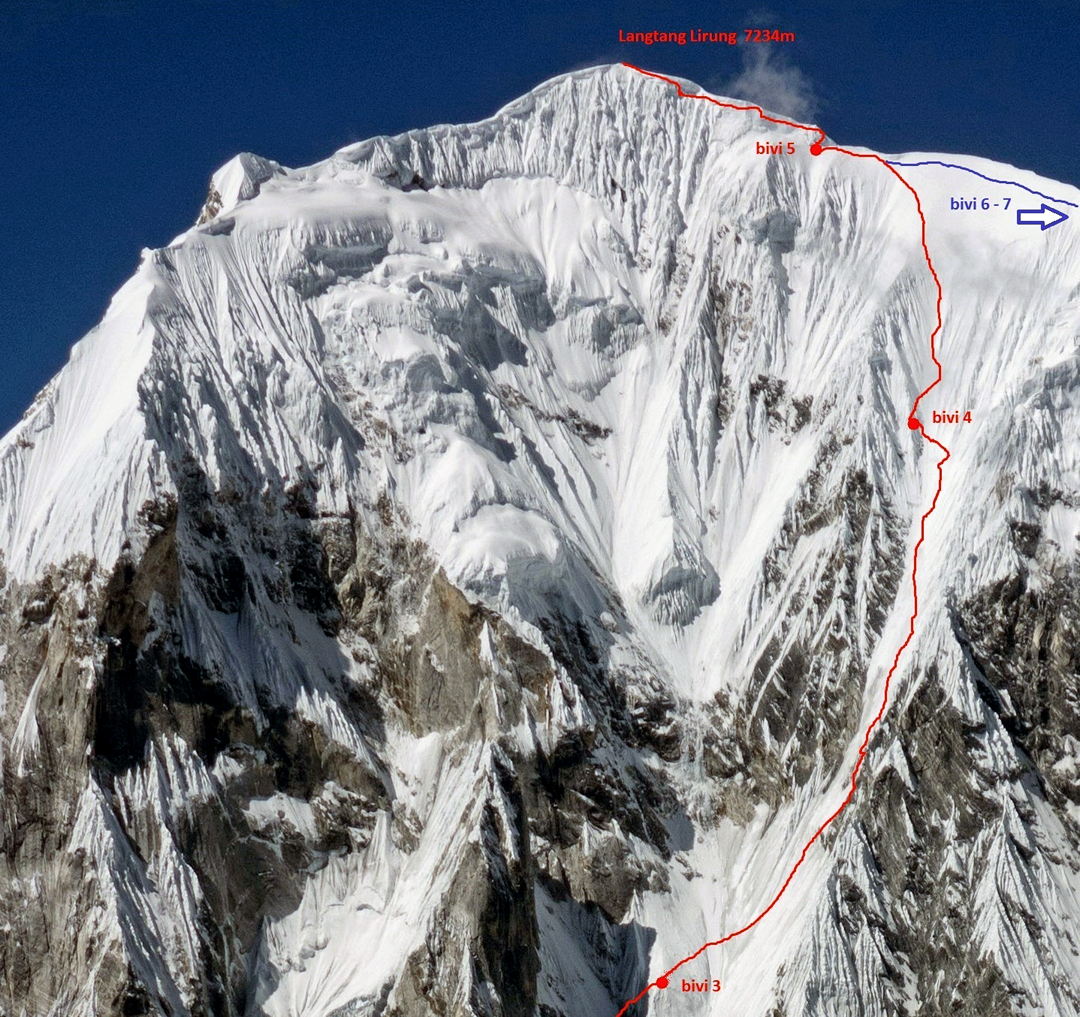

On the 25th, Ondra Húserka and I set out from advanced base for a second attempt. The climbing was difficult, with steep, air-saturated ice. We needed to move fast, and Ondra, in the lead, climbed brilliantly, like a motor mouse. At one point we were hit by a big avalanche that pummeled my head and shoulders. We began simul-climbing to move out of the dangerous central couloir and reach a sheltered bivouac site, at 5,500m, on a rocky spur—but not before a second avalanche hit Ondra on the head and gave me a Thai massage, unfortunately without any coconut oil.

The next day brought difficult climbing over smooth rock, followed by an icy couloir and more mixed terrain. We progressed slowly and bivouacked at 5,800m. On the 27th, we climbed to 6,300m. This day gave the most difficult climbing on the route, with a particularly taxing rock section to reach the central funnel. We were forced to place our tent on a slim rib. Ondra worried we could be swept away, but there was no better option.

Fatigue was beginning to take its toll as we headed right on steep ice the following morning. By late afternoon, the wind started to blow and both of us were shivering as we scanned the terrain for a possible tent site. Finally, behind one of the snowy curls at around 6,800m, we found a small cave. At least we could sit down and stretch our legs.

On the 29th, we reached the northeast ridge, atop the face, and bivouacked at 7,100m, taking all day to climb 300m. I had taken the lead, switching off my brain and counting steps as I plowed through powder snow. We both slept well at our nice, flat campsite.

The following morning was beautiful, with no wind. Knowing the top was close, we left everything except the rope and, moving together, reached the summit at 11 a.m. For around ten minutes, we were happy and had no worries. Then it was time to return to our tent, pack up, and continue down the northeast ridge. We eventually dropped onto the east flank and bivouacked at 6,300m. Below, a wild glacier descended toward the foot of the mountain.

Cold and exhausted, we packed our frozen gear the next morning and started down again. In deep, avalanche-prone snow, Ondra, 60m behind me, kept the rope tight. At the top of a huge serac wall, I looked down at a view that filled me with horror. We had managed to zigzag between risks to this point, but now we would have to descend the face directly with at least four rappels. Prioritizing speed in this dangerous area, we chose to rappel simultaneously. At one point we were hit by a swarm of falling rock and ice, which made a crater in Ondra’s helmet and caused him to bite through his lip. At last we reached a glacier plateau and hugged each other, as we felt we were out of major danger.

We continued down, circumventing or leaping crevasses. At around 5,500m, I drilled an Abalakov anchor and backed it up with one of our two remaining ice screws, then rappelled a short distance. I stepped over a narrow crevasse and walked a little way until I saw we would need to make another rappel.

Moving back up to below the narrow crevasse, I shouted to Ondra to start rappelling. A moment later there was a dull thump followed by strange rustling sounds. I rushed up to find the ropes disappearing into a narrow crack in the ice. The Abalakov had failed, and Ondra had fallen into the crevasse.

I rappelled into the slot and located Ondra in total darkness, but I was unable to rescue him despite a struggle lasting hours. He had serious injuries, and they proved to be fatal. After confirming he had passed away, I regained the surface and got into my sleeping bag.

The next morning, I sent several messages, including one to Ondra’s girlfriend, so she would receive the news directly from me. Then I left my sleeping bag as a marker and started down through a maze of crevasses and ice towers, again making short rappels. In late afternoon, I finally reached our empty base camp and, having a strong desire to talk to someone, changed into approach shoes and went down to Kyanjin Gompa.

The next day, I was taken by helicopter to locate the accident site and later flown to Kathmandu to deal with formalities. Ondra and I did not have time to think of a route name, so I will do that myself: Ondra’s Star. [On November 7, a strong Sherpa team was helicoptered to the accident site and was able to extract Ondrej Húserka’s body by long-line.]

—Marek Holeček, Czech Republic