Edge of Entropy: Gasherbrum III's West Ridge

Pakistan, Karakoram, Baltoro Muztagh

For many years I’ve asked myself, What would be the most difficult route you could climb, at the highest altitude? Could I take the challenge of places like the Alps, Alaska, and the Canadian Rockies, then supercharge that to the world’s tallest mountains, somewhere around 8,000 meters? That would be a real beast.

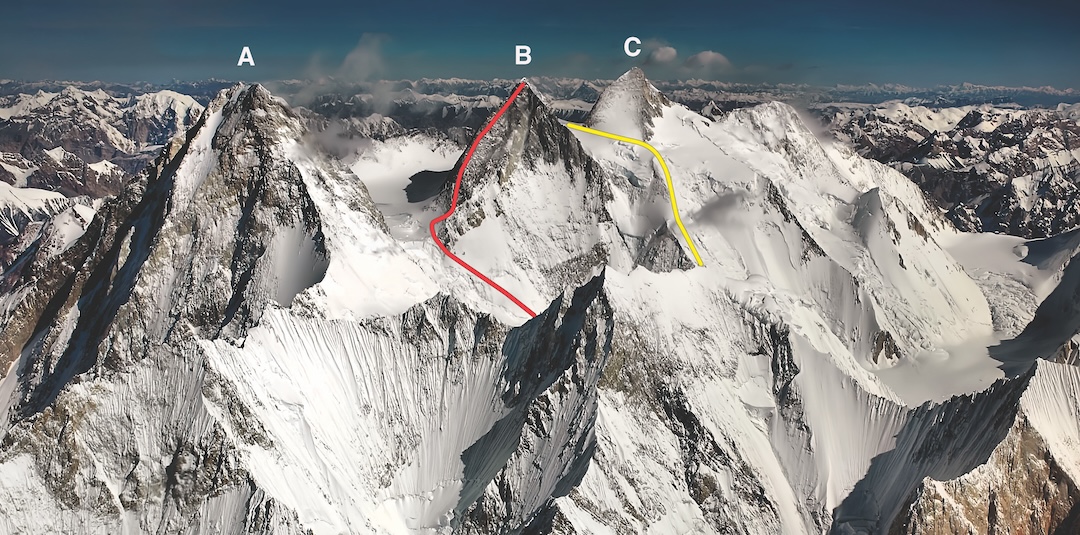

Gasherbrum III (7,952m on maps) is often ranked as the world’s 15th-highest peak and had only been climbed twice, both times from the east. Aleš Česen invited me to try the unclimbed west ridge in 2022. A few years earlier, we had made the second ascent of Latok I together, along with Luka Stražar, but Gasherbrum III was more than 800 meters higher. Of course, we knew it wouldn’t be possible to climb quite as hard as we could at lower elevations, but Aleš and I were keen to explore the possibilities.

The west ridge’s 950-meter spine of dark granite looked appealing. We wanted a route that would be difficult, but not overly so. The line seemed as if it would be quite safe objectively, since it’s mostly on an arête. The rock appeared solid, unlike on many of the Gasherbrum peaks made of crumbly marble and limestone. And the descent would be down the normal route of neighboring Gasherbrum II. The line looked psycho—but not too psycho.

The west ridge of Gasherbrum III had been attempted only once, in 1985, by Scottish climbers Geoff Cohen and Des Rubens. [The Scots called this feature the southwest ridge, but the majority of the ridge runs westward.] Cohen and Rubens put in an impressive effort, reaching about 7,700 meters on their second day on the ridge, but then bailed due to poor weather and slow progress—they had left their bivy kit lower down, hoping to summit and return the same day.

Our attempt in 2022 explored the balance between desire and rationality. Camped near the start of the ridge at around 7,000 meters, we watched and listened to extremely strong winds ripping over our objective. I mean “rip” literally, in the sense that a tearing sound emanated from the mountain. We really wanted to climb the ridge, but it seemed likely we would be blown off the peak. Rational thought prevailed, so we contoured around to the northwest side of Gasherbrum III, hoping for shelter. We climbed for two days up easy snow and mixed steps until, at about 7,650 meters, we hit a 100-meter-high granite tower. This formation reminded me of a smaller version of Tengkangpoche’s northeast pillar, a line I had climbed a few months earlier, taking seven days and lots of aid. Aleš and I felt we’d be out of our depth to attempt such a difficult tower at that height, so, again, rationality prevailed.

Climbing with Aleš is great fun, and I trust him completely. After three big trips, I don’t think we’ve ever argued. Planning a rematch in the summer of 2024, we reflected on our experiences together, including Latok and our prior attempt on G-III. We figured we’d only have one shot to climb Gasherbrum III, because we would be wasted by the altitude and effort after a single try. Patience would be key because, with base camp located at 5,000 meters, we knew we would recover very slowly from our acclimatization forays. We planned a trip lasting two months, in order to give us the best chance of success.

To reach base camp, shared with climbers aiming for Gasherbrums I and II, you walk up the Baltoro Glacier for six days, covering 112 kilometers. Once there, over the course of about three weeks, we made three trips some ways up G-II’s normal route, the southwest ridge, to acclimatize. (We planned to use the same route to descend from Gasherbrum III if we made it to the summit.) During this period, there were always strong westerly winds at high altitude. G-II is just over 8,000 meters, and about 40 people per year attempt it. They usually jumar fixed ropes that are installed every season, use supplementary oxygen, and have a lot of Sherpa support. There are exceptions to this, and we didn’t use any of this assistance during acclimatization.

Poor weather meant our first two acclimatization trips were shorter than we’d have liked, so we planned a third trip to be sure we’d be prepared. On July 20, our 30th day in Pakistan, we spent one night at 7,000 meters. Unfortunately, in the morning, Aleš became very dizzy; he felt the spins as we descended to Camp 1 and then on to base camp the next day. It was impressive that he was able to keep it together during this descent. The cause of his dizziness was uncertain, but we suspected an inner ear issue.

We rested for a week and tried to find some medicine that might be helpful. There was a pleasant scene in base camp, thanks to a neighboring group of Austrian climbers and some American skiers. Aleš improved gradually. We missed a good weather window during this time, and afterward the conditions deteriorated somewhat. But when Aleš had recovered sufficiently, we decided to take our one shot.

Leaving base camp on July 31, we slept at Camp 1 for Gasherbrum II, at almost 6,000 meters, a spectacular site in the middle of the South Gasherbrum Glacier, surrounded by enormous peaks. On our second day out, we climbed a long icefield to reach the basin between Gasherbrums IV and III, skirting the nasty icefall that plunges from the basin by scaling the icefield to the right. [This icefall is where, later in August, three Russian climbers were hit by an ice avalanche while searching for the body of Dmitry Golovchenko, who fell from the southeast ridge of Gasherbrum IV during an attempt in 2023. His climbing partner on that attempt, Sergey Nilov, died in the avalanche on August 17, 2024, and two others were injured and required a rescue.]

Aleš and I camped that night at around 7,000 meters, at the foot of G-III’s west ridge. Our packs were quite heavy and our throats already dry.

On August 2, our first real climbing day, we started up the west ridge. About 100 meters up, piled under some rocks, we found a coiled rope that the Scots had left during their descent, 39 years earlier. It felt fantastic to be really climbing after so much time acclimatizing. We pitched steep rocky slabs, thankfully with plenty of holds, then climbed snowy mixed ground, each of us leading a bunch of good pitches, including a dinosaur-spine arête. In midafternoon, at 7,485 meters, we stopped to bivy amid some rocks.

For breakfast, we launched onto the upper ridge. In falling snow and light winds, we tried to keep moving up, climbing thrutchy chimneys and steep steps. Above, we could see a headwall near the end of the ridge. Although perhaps only five big pitches high, it looked quite menacing, so we eyed a potential bypass to the left. In late afternoon we stopped to bivy beneath this wall, at 7,800 meters. Unfortunately, we were unable to cut a platform big enough for the tent and were forced into an open, sitting bivy. The cold kept us awake, as did the snowfall piling onto our double sleeping bag. I’m sure we fried a few brain cells that night. Alpinism is such a beautiful trap, a constant struggle between what you want and what you need. Part of us simply wished we could be somewhere else, more comfortable, but somehow we needed to keep climbing.

In the morning, without much discussion, we started traversing left to bypass the headwall. In hindsight, it’s possible we took not only a longer route but also maybe a harder one. The rock slabs coated with fresh powder snow were quite difficult and insecure. Deep, collapsing snow also took a lot of energy. A final difficult pitch stopped us at around 7,900 meters. It had about 15 meters of steep, awkward climbing and no protection. After seconding the pitch, Aleš said, “I don’t know how you climbed that.” It feels impossible to grade such a pitch at that height—maybe about M6?

On the summit, we felt knackered but also very relieved the route had worked out. Our two inReach devices and watch all recorded 7,958 meters. There was no evidence of other life on top, human or otherwise. Nothing we could see, as far as the horizon, implied life could even exist in such places. It’s hard to describe, but it had felt as though we’d become slightly less human the higher we climbed. If being human is having conscious thoughts and experiencing emotions, we certainly weren’t all there at some points during the climb.

We made about ten rappels down the east side of the mountain, descending the line of the only two previous ascents of Gasherbrum III (first climbed in 1975 by Alison Chadwick-Onyszkiewicz, Janusz Onyszkiewicz, Wanda Rutkiewicz, and Krzysztof Zdzitowiecki). Then we traversed over to the normal route of G-II and bivvied at Camp 4 (7,400m). The next day, we continued down along the many fixed ropes abandoned after the 2024 attempts and earlier seasons on G-II. Stylistically, it would have been preferable not to use these ropes, as we had avoided them while we were acclimatizing. It would have felt completely contrived, however, to make our own V-threads right next to other climbers’ anchors and ropes. On August 6, we retraced the familiar steps down the South Gasherbrum Glacier to base camp. A few days later, happy but hungry, we trekked over the Gondogoro La and down to Hushe, the nearest village, where we feasted on eggs and chapatis.

It had been very satisfying and interesting to achieve my long-term goal of experimenting with climbing technical pitches at high altitude. I think we learned a great deal about how depleting the altitude can feel, yet how it’s still possible to function and climb, thanks, in part, to a good partnership. It’s also true that high-altitude climbs take a lot of time, energy, and money, and, for now, more difficult climbing at lower elevations occupies most of my thoughts. However, I’m still very curious about pushing this other aspect of alpinism. And besides, my original idea had been to climb to “around 8,000 meters,” so there’s obviously still room for improvement!

SUMMARY: First ascent of the west ridge of Gasherbrum III (7,958m GPS), by Aleš Česen (Slovenia) and Tom Livingstone (U.K.), with descent by the original 1975 route on the east face, then down the southwest ridge (normal route) of Gasherbrum II. The round trip from base camp took seven days (July 31–August 6); the pair spent three of those days climbing the 950-meter west ridge and descending the east face.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Tom Livingstone is a British climber who lives in Chamonix, France. He wrote a feature article for AAJ 2020 about the first ascent of the northwest face of Koyo Zom in Pakistan’s Hindu Raj. About this year’s expedition, he said, “This climb was a very rewarding experience with a great friend. Cheers, Aleš.”