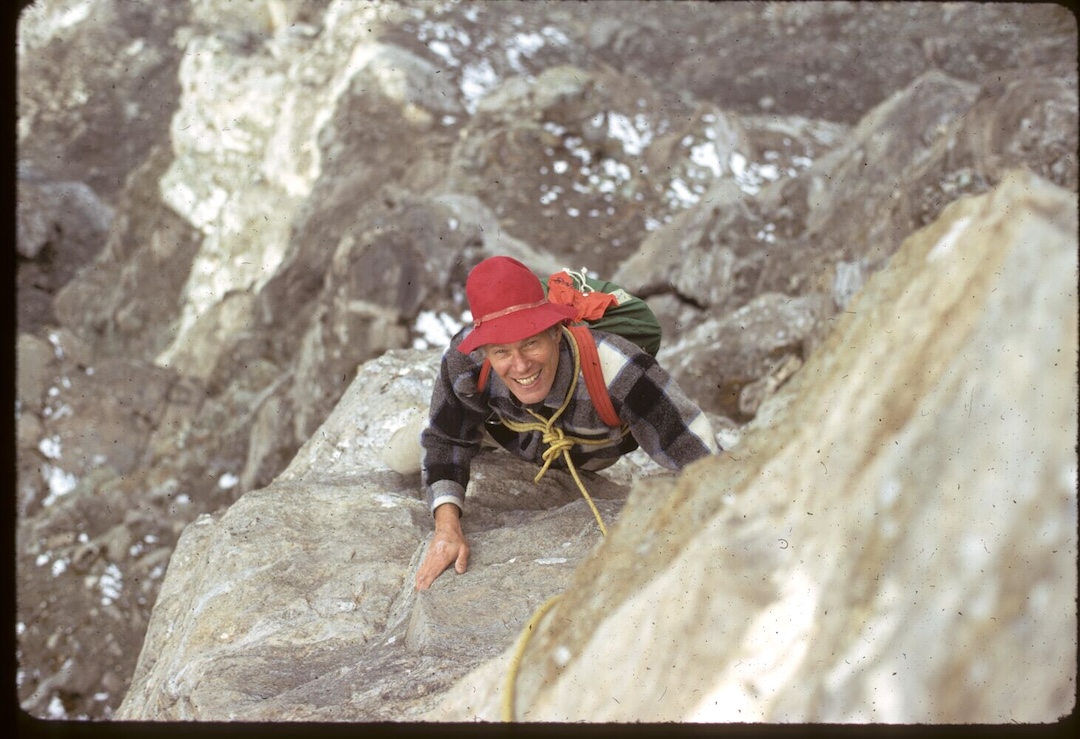

Fred Golomb, 1924–2024

Dr. Frederick Golomb often said, as his children recall, “I’m the luckiest man in the world.”

Depending on which way things went at several major junctions, Dr. Golomb might well not have survived to say it.

As a young man raised in the Bronx, already a skier, he eagerly enlisted in the 10th Mountain Division corps, yet in the Army Specialized Training Program he scored so high on an aptitude test that he received the opportunity to attend Yale University (class of 1945) and the University of Rochester Medical School (finishing in 1949). In World War II he did not go overseas, where nearly 1,000 from the 10th were killed and many more wounded.

In 1953, Dr. Golomb served in Korea as chief of surgery in the 44th MASH unit. In 1954, as he tended to a wounded soldier in the field, his hand and leg were injured in a grenade explosion that he was fortunate to survive. Golomb received a Purple Heart.

He also was invited by Charles Houston as expedition doctor on the tragic, legendary 1953 expedition to K2. Says Phil Erard, a longtime friend of Golomb, “He told me his hospital work prevented it.” Nearing the summit on K2, the climbers were pinned in a storm, during which Art Gilkey, age 26 and a close friend of Golomb’s, fell ill with thrombosis. As his teammates tried to rescue him, Gilkey was swept away and the others nearly suffered mass disaster, saved only by Pete Schoening’s famous boot-axe belay.

Golomb’s mountain experience was varied and broad. His early endeavors included a stint in early winter of 1943 working with Joe Dodge, hutmaster at Pinkham Notch in the White Mountains, New Hampshire, to gain experience while waiting to join the 10th. In August 1948, he climbed the Grand Teton with Dick Emerson, and the two were first to suss out a rappel into the Upper Saddle, a version of the now standard descent. In the early 1950s, he climbed in the Gunks with Gilkey, Hans Kraus, Bonnie Prudden, and Fritz Wiessner.

In the summer of 1951, while on a geology-research expedition with the scientist and mountaineer Maynard Miller, Golomb did several first ascents on the Juneau Icefield in Alaska. He named a 7,000-foot peak Everlast (58.783801N, -134.158670W), after his father’s boxing-gloves company. He was an AAC member from 1952.

In 1954, home from Korea, Golomb wed Joan Schneider, enjoying a long marriage until her death in 2011. Fred had a long climbing partnership with his son, James, a neurologist at NYU, where his father had completed his residency and also practiced—they overlapped there for 14 years.

“We were really best friends,” says James. He describes his father as methodical, a calculated risk-taker, good-humored, and ever optimistic, typically saying amid poor weather, “I think I see a little bit of blue up there. I think it’s breaking up.”

The two climbed in the Gunks and in New England, the Rockies, Cascades, and mountains of Alaska, and they did annual ski mountaineering trips to France for nearly two decades. Fred continued ski alpinism well into his 80s, and at 87 became the oldest known person in France to learn paragliding and fly solo. In 1981, he and James attempted a 6,700-meter mountain in the Barun Valley of Nepal.

“The weather got bad and we went up too fast,” James says. “Fred developed cerebral edema and started hallucinating at 6,100 meters, so we turned back.

“One of our Sherpas fell unroped into a crevasse,” he added. “We spent hours looking for him and hauled him out as darkness descended. Fred sutured his head wound.”

Golomb taught his daughter, Susan, who is a prominent New York literary agent, to ski at age three, and he “was proud and thrilled,” Susan says, when she “caught the bug” and climbed in the Gunks.

Professionally, Golomb was a revered surgeon who participated in milestones in medical history. At Johns Hopkins, he worked with Dr. Alfred Blalock to address heart issues in newborns. Golomb became director of NYU’s chemoimmunotherapy division and was a pioneer in melanoma treatment. He trained in plastic reconstructive surgery, devising a Z-plasty operation drawing on his experience at the 44th MASH. Susan remembers him saying once that he had “made someone a belly button.”

An obituary by Alumni of Bellevue Hospital stated: “In the operating room, Dr. Golomb took pride in working cleanly and efficiently, collecting data obsessively in order to learn, publish, and improve. He was known for his grace, cheerfulness, and disdain for argument or accusation.”

Somehow he found time for many other interests. Golomb had attended the High School of Music & Art to study portraiture and sculpture, and as an adult was an offshore yachtsman, a windsurfer and a kayaker, and raced a Porsche. He made a film about his lifelong love of the mountains. He often said, “I am a surgeon in New York, but I climb mountains for a living.”

“My father had no regrets,” Susan says. “He did everything he wanted to do, he knew he was loved, and he really cared about the alpine world.

“He was always there for me. He was such a good father and such a good doctor. He was able to balance it. He did it with kindness. He never raised his voice.” She remembers how, though he put in long days of surgeries and commuting, he “always came home with a smile on his face.”

He is survived by James, Susan, and a grandson, Jacob Martin.

—Alison Osius