Three Modern Aid Routes on Baffin

Canada, Nunavut, Baffin Island, Auyuittuq National Park

“Just drill something already, damn it,” I mutter under my breath as Brandon hooks farther and farther above the belay ledge. Sam and I listen anxiously to every creaking adjustment of steel on stone, willing the placements to hold. CRACK! The rock breaks under a hook and sends Brandon flying. One beak after another rips out.

The fall is long enough for us to wonder if anything is going to hold. Suddenly the rope pulls tight and catches Brandon a few feet above the ledge. He’s staring at Sam and me with a rack of beaks clipped to the lead rope, sitting in a heap against his harness. A single rivet from the hardware store had kept him from hitting the ledge. I light a cigarette and pass it over.

For Brandon Adams, Sam Stuckey, and me, big walls are one of the main reasons we fell in love with climbing. Each of us was drawn like a moth to a flame to the crucible of American rock climbing, Yosemite Valley. While steadily honing our craft on the soaring granite walls, we each harbored the same dream of establishing first ascents on Baffin Island, a mythical arena of massive walls rearing out of the sea, ice, and rugged valleys.

Some of Baffin’s biggest and remotest walls were climbed in the 1990s, a time when helicopters were used for certain approaches and the typical strategy relied on extensive fixed ropes and capsule-style siege tactics to put up new routes in the harsh and unpredictable environment. Nowadays, lighter and more advanced gear, reliable weather forecasting, and modern Yosemite tactics like short-fixing and simul-climbing make such cumbersome approaches unnecessary. A modern hard-aid rack consists of a healthy assortment of beaks and hooks instead of the traditional sawed angles, knifeblades, copperheads, and nuts.

Today’s focus on free climbing has pushed hard big-wall climbing out of the spotlight. But that doesn’t mean it isn’t still being done at cutting-edge difficulty. On El Cap, people had been saying for years there were no big unclimbed lines left to do, but Brandon established two new routes recently, in 2018 and 2021. These routes are prime examples of modern hard aid: pushing the latest gear available to its absolute limit.

This kind of big-wall climbing satisfies not only creative problem-solving but also aesthetic exploration. In Rock and Ice 24, Dale Bard espoused his perspective on wall climbing: “Then you get into what I was eventually doing—going up on El Capitan for the location. While sitting in El Capitan’s Meadow and staring up at the wall, I’d see something real pretty. Over by Iron Hawk, there’s a beautiful orange swirl that looks like it’s painted on the wall. I wanted to go up there, so I did.” To the big-wall climber, the most outrageously steep, blank, and direct aspect begs the question: Can we go up there?

Brandon and I met in the Valley in 2018 when I was a climbing steward and he was a climbing ranger. Brandon approaches everyday life with a bumbling bear sweetness that disappears as soon as he enters the vertical, revealing maniacal intensity and hyperactive focus. He climbs every pitch like it might be his last, with a beak tattooed across his chest and Tool blasting on his phone.

Over the years, we’ve shared many days roped together, setting speed records on El Capitan and exploring the High Sierra. Many of my climbing firsts have been with Brandon, from learning how to drill a bolt to discovering the laborious process of establishing new routes. While descending from the Incredible Hulk in the summer of 2022, he asked if I was interested in climbing on Baffin Island. The seed was planted.

I first heard about Sam when he made a rare repeat of Jolly Roger (Cole-Grossman, 1979), an A4+ R testpiece on El Cap. Sam is another fanatic for hard aid routes, having climbed over 100 desert towers, including nearly everything in Utah’s Fisher Towers. When Brandon partnered with Sam to climb Continental Drift on El Capitan (Anker-Gerberding-Thaw, 1997), he asked Sam if he too was interested in going to Baffin.

In the fall of 2023, the three of us committed to planning the expedition. Sam and I roped up for the first time in Yosemite in the spring of 2024. We climbed well together and quickly bonded over his encyclopedic knowledge of obscure film and music. The Baffin team was forged.

In March, the three of us gathered in Salt Lake City to compile the necessary supplies to be shipped to Pangnirtung and cached in advance beside Summit Lake, about 30 miles up the Weasel Valley, when snow machines could still access the valley. We packed two lead lines, one haul line, a double rack of cams, a couple of dozen beaks, a pile of bolts and bits, and a fistful of rivets. We loaded buckets with food, consisting mostly of couscous, the king of expedition grains. Entangled in a labyrinth of shipping manifestos, spreadsheets, and Canadian import restrictions, we held our breath as the gear shipment cleared customs—then lamented our nonrefundable flights when our food shipment was rejected at the border.

To save us from hundreds of miles of backbreaking load-ferrying, Sam flew to Ottawa at the last minute and frantically acquired food in Canada, then shipped it on to Pangnirtung. Without Sam’s commitment, I have no doubt that our expedition would have been vastly less successful. All of our gear and food made it to local outfitter Peter Kilabuk in Pangnirtung to be cached at Summit Lake.

On July 6, we landed on a dirt runway, relieved to see that the remaining sea ice in Pangnirtung Fjord had been blown out by strong winds the day before our arrival, allowing us boat passage to the end of the fjord, where it meets the Weasel River. We then spent six days hiking with nearly 90-pound haulbags, enjoying the pleasure of every variety of post-holing along the way: boggy tundra, river crossings, quicksand, moraine, talus, sand dunes, and deep snow. Brandon joked that falling into a crevasse would merely be the ultimate post-hole.

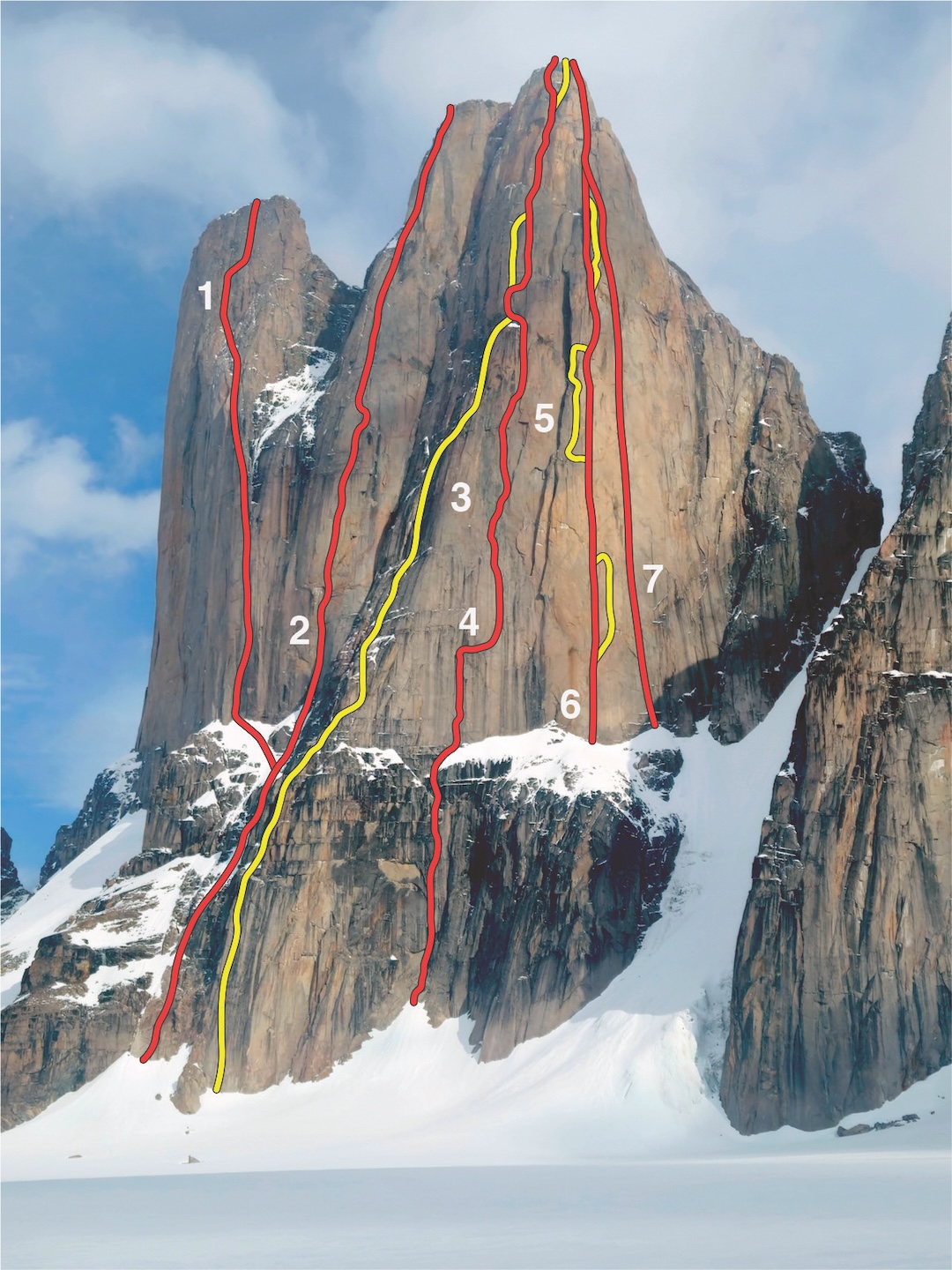

With 24-hour daylight, we would hike until we were deliriously crippled and then sleep until we could walk again, losing track of the calendar days. Almost a week of toil brought us to our first base camp, a couple of miles up the Turner Glacier, below the northwest face of Frigga I (1,264m). Using the buckets from our gear shipment as snow shovels, we excavated a platform for the tent. From here we could see up the Parade Glacier, an offshoot of the Turner that lies between the west face of Frigga I and the east face of Mt. Asgard (2,015m), and the striking east face of Mt. Loki (1,920m) a few miles farther away, guarding the head of the Turner Glacier.

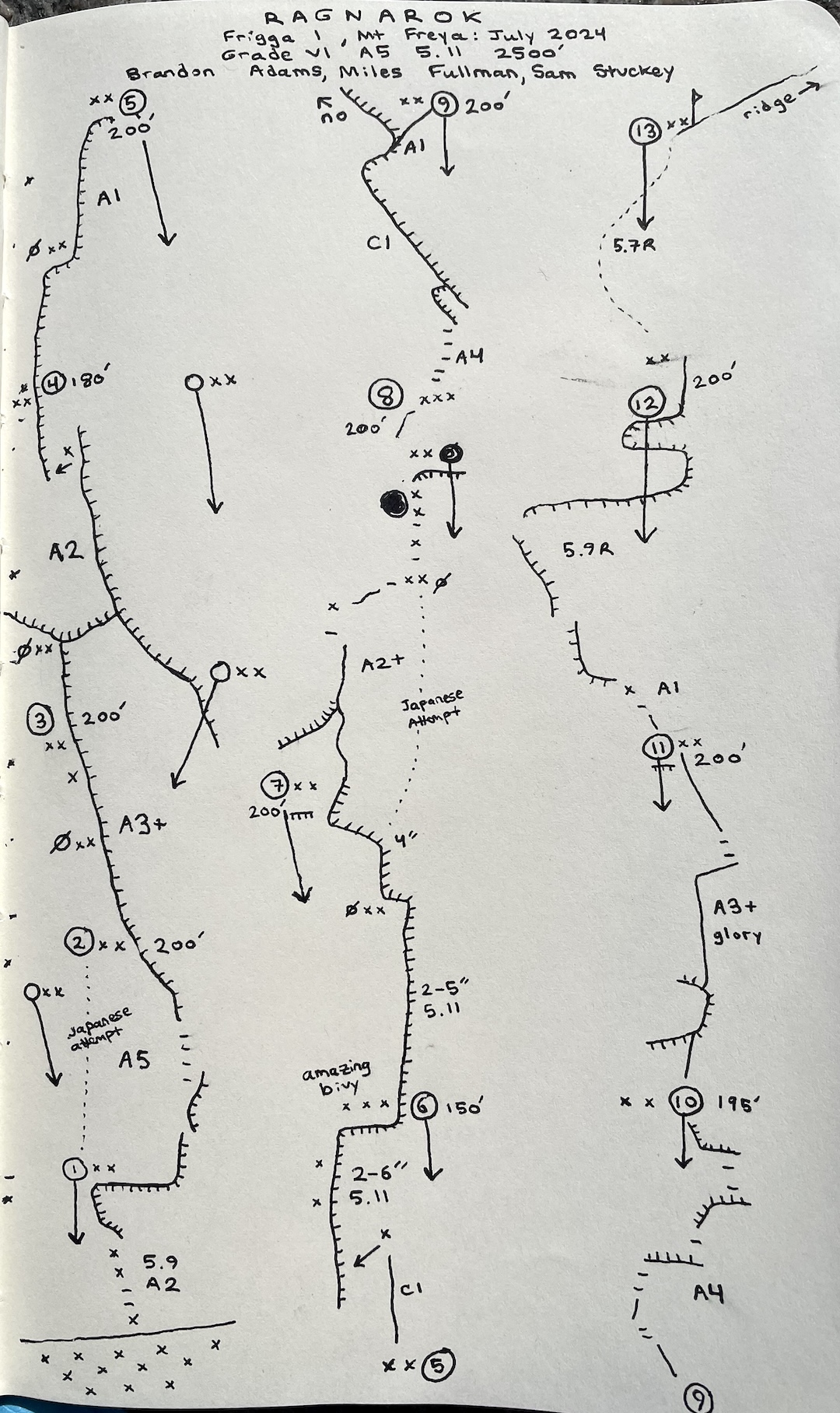

On July 15, we hiked our gear up to the menacing west face of Frigga, which persistently overhangs and tapers to a point like a sword. There is only one other route on this formation: Slith the Frightful (Barker-Rzeczycki, 1996), on the left side of the west face. In 1998, Japanese climbers attempted to climb the right side of the west face (AAJ 1999). Unsure of their line’s exact location, we aimed for an obvious natural system of sweeping corners and splitter cracks skirting the right edge of the face.

We started climbing on July 16. Sam led us off the snow, and we strained against the heavy bags. Brandon quested above the belay ledge, with delicate hooks on fragile flakes and baby beak placements in friable rock, a true master of his craft. While I was cleaning the pitch, it started raining heavily and I got soaked to my skin hammering out beaks in a waterfall. I pried loose a large flake that Brandon had hooked across—it hung directly above the ledge where we had just belayed. As I levered it outward, it sheared off a significant plate of the wall. We watched, transfixed, as it obliterated the belay ledge. Our vulnerable position, 60 miles from Pangnirtung, began to sink in.

Climbing the next pitch, we encountered hangerless bolts, discovering that the line we had scoped overlapped in places with the aborted Japanese attempt. At our first bivouac, we almost set the portaledge on fire while priming the stove in our homemade hanging kit for the first time.

To conserve our limited anchor hardware, we strove to make every pitch a full rope length, drilling anchors with one rivet and one bolt. Carrying everything on our backs into the mountains had necessitated spartan choices about equipment, but using the bare minimum of gear to accomplish our goals also became one of the most engaging challenges of the expedition. We had just enough of everything to see us through our objectives with a thin margin for error.

The climbing continued to be engaging, alternating between soaring beak seams and splitter cracks. Leading the offwidths with sparse protection was especially exciting while bypassing delicately perched chockstones, which could easily have killed the belayer if dislodged.

We reached what was clearly the Japanese attempt’s high point—a reported 300 feet from the summit—and continued up for about 800 feet more climbing. On the fourth day we pushed for the summit, leaving our haulbags on a ledge halfway up the wall.

Unencumbered by hauling, we moved more efficiently. The leader would often be short-fixing the next pitch while the follower finished hauling and the third person tagged up gear or drilled another bolt at the anchor for the descent. The Japanese attempt had taken 27 days, and Slith the Frightful was established over 17 days. With the advantages of modern tools and tactics, we would climb and descend our route in four and a half days.

The climbing to the [ridgeline] turned out to be some of the best: A steep and exposed pitch accessed a perfect headwall, where rope-stretching beak seams led to a final pitch of free climbing over wet, creaking plates. We sat on the snowy ridgeline and marveled at the majestic frozen panorama.

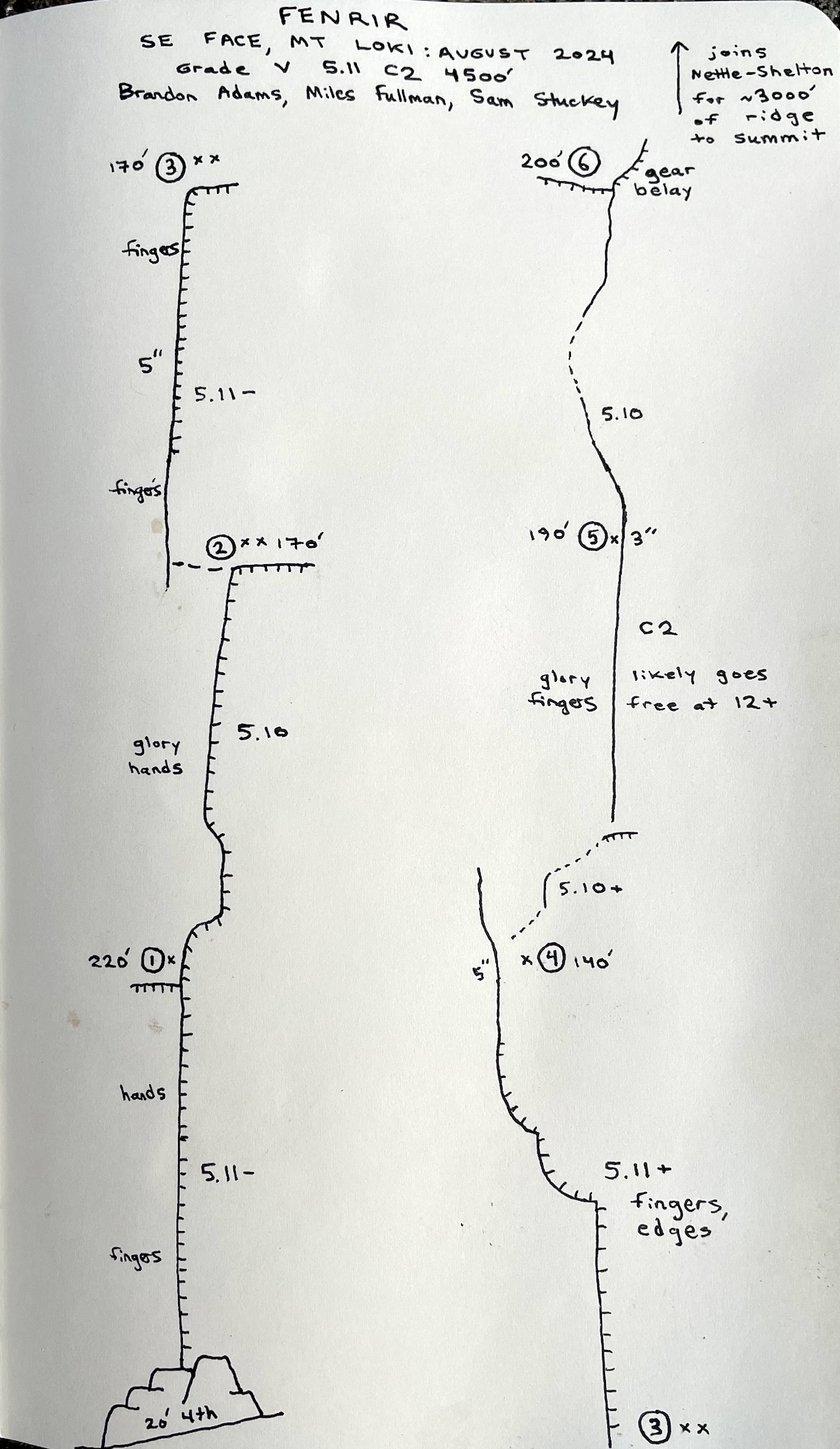

We spent July 21 to 23 shuttling everything to a new base camp on the moraine below the east face of Mt. Loki. We were relieved to relocate, as the rapidly melting glacier was turning our first camp into a lake. As we were shuttling our gear up the Turner Glacier, we noticed a system of corners splitting the captivating eastern wall on Loki. This aesthetic peak, sometimes called the Matterhorn of Baffin Island, had three existing routes: the west ridge (Baird-MacCallum-Morton-Paul, 1965), the south buttress (Lee-Parker, 1982), and the southeast ridge (Nettle-Shelton, 2013). But the steep east face was unclimbed.

Stormy weather kept us tentbound for a week. To pass the time, we made crosswords for each other with words from a book of Norse mythology. We learned the stories behind the names of the mountains surrounding us, such as Asgard: hall of the Aesir, the warlike Norse gods. The Inuktitut names for the formations were more literal, Asgard being named Qattaujannguaq, which translates to “looks like a barrel.”

In Arctic Dreams, Barry Lopez writes, “Language is not something man imposes on the land. It evolves in his conversation with the land.” As we lived on the glacier surrounded by these enormous walls, we learned the names for the peaks that had evolved out of the people’s relationship with them, logical in their referential description, and the names that had been bestowed on them by wayward adventurers. Somewhere in the intersection of these two relationships with place, one as an inhabitant and the other as a pilgrim, we formed our own connection with these wild mountains.

A brief lull in the weather allowed a reconnaissance of Loki. Hiking past the toe of the southeast ridge, we scrambled along a talus field slanting up below the east wall to the highest point, where a sweeping system of splitters rose up the smooth buttress. While we waited for the storm to break, we free climbed the corners and cracks at the start of our line and fixed three pitches.

On August 1, we ascended our fixed lines and continued to the summit of Mt. Loki. Brandon pushed the rope up the lower wall while I freed the pitches on Micro Traxion. The most memorable section involved thoughtful face climbing into a striking finger crack; I fell on the pitch but estimated it would go free in the 5.12 range. We named this pitch Gleipnir, after the unbreakable, ropelike material the Norse gods used to bind Fenrir the wolf, Loki’s child, until he escapes during Ragnarok, the foretold end of the world in Norse mythology. Maybe someone will get inspired to repeat our route and free Fenrir from his unbreakable bonds.

At the top of the 1,500-foot wall, we traversed left below a large overhang to join the southeast ridge, then followed this for another 3,000 feet or so, mostly soloing and simul-climbing a few sections. From the summit, the view to the northwest over the Penny Ice Cap extended incomprehensibly. Massive snow domes slumped surrealistically atop bristling formations in every direction. We descended to the south, making 13 rappels down the south buttress, and stumbled over crevasses to base camp in the early hours of the following morning.

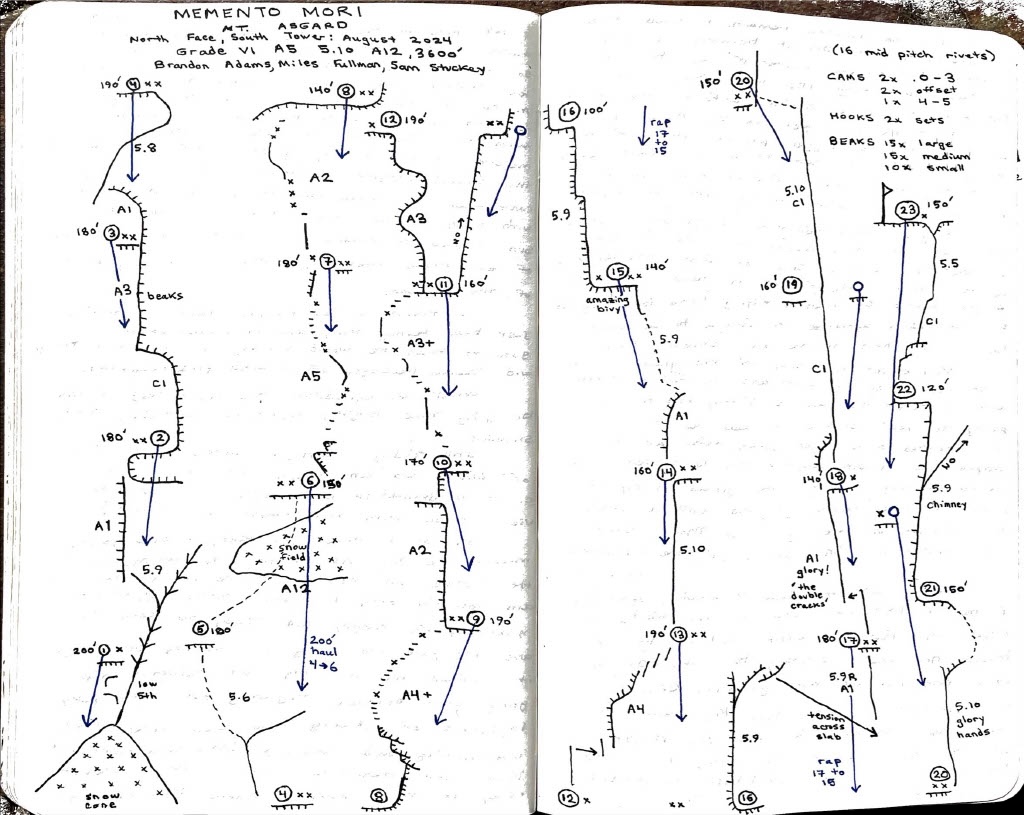

The good weather continued, and we knew we had to make the most of it, so the next day we ferried loads across the Turner Glacier and fixed ropes at the bottom of the south tower of Mt. Asgard. We had scoped a line up the blankest stretch of wall between Sensory Overload (Lavigne-Papert-Walsh, 2012) and The Bavarian Direct (Bruckbauer-Grad-Guscelli-Reichelt-Schlesener, 1996); the latter was freed in 2012 by Alex and Thomas Huber, with a set of variations, discovered in 2009, known as The Belgarian (VI 5.13c).

We started climbing where the rock meets the glacier, a ways to the right of Sensory Overload. On August 4, we hauled our last loads off the glacier and committed to the wall.

That first day we climbed over 1,000 feet, making a hanging bivy following a hard and consequential pitch that Brandon later named “No Parachute, No Ground,” after a concept in the meditation book he was reading. A fitting description of the mental game of dangerous aid climbing, if you ignore the very real ledge Brandon nearly hit while ripping the pitch. After a few drags and a slap on the helmet, Brandon re-racked all of the beaks piled on the lead line, pulled back up to the single rivet that had caught his fall, and started tapping beaks back into the same placements.

The wall was unrelenting, interweaving thin seams and flakes. Every rope length was slow going and hard won, a sustained puzzle requiring ingenuity and delicacy. By this point the three of us had merged into one organism, the rhythms of wall climbing feeling familiar and instinctual. We each tacitly set to our respective tasks, confident in the knowledge that everyone was doing their part. After two successful ascents, we felt more at ease in the Arctic environment, and the looming wall began to seem more like an old friend than a menacing adversary. It felt like we could keep going forever, climbing walls that never ended until the sun circled below the horizon and the polar night froze us to the rock. Steadily we pieced together the imaginary line, upward through the myriad uncertainties.

We shared smokes at belays to calm frazzled nerves, taking in the long waves of light spilling over the glaciers in great amber swaths. Clouds encircled us and danced in wreaths around the summit of Loki; great wisps of fog swirled below, above, and around us. The Arctic stillness made the rhythm of the hammer all the more piercing.

At a long belay, Brandon asked if I had thought of any good names for the route, and I suggested Memento Mori: “Remember you must die.” It seemed appropriate, a reminder of the experience we had been sharing on this huge wall, a reminder of the inevitability of our own mortality and a call to make the most of our fleeting time.

We checked the forecast and learned that our weather window would be closing soon, so we pushed hard, constantly unsure if there would be enough climbable features, to reach a big bivy ledge and then charge for the summit. Above the ledge, we continued up a corner and then Sam brilliantly traversed rightward to the base of an immaculate crack system, reminiscent of the Shield headwall on El Capitan. I fixed one aesthetic pitch and looked up before descending for the night to see the splitter extending to the heavens.

The next morning, anxious to stand on top and descend before the weather hit, I started short-fixing from the top of the fixed lines and pushed the rope up the final thousand feet in just four hours. The rock was impeccable, and the climbing and position phenomenal. We reached the top just after noon and spent another four hours relaxing in the sun on the uncannily flat summit, admiring rock crystals and reveling in how strange it felt to stand atop one of the mountains of our dreams.

As I gased over at Frigga I’s magnificent west face and the route we had called Ragnarok, the name’s apocalyptic significance in Norse mythology seemed fitting from this perch: The beginning is the end, and the end is the beginning.

The next day we rappelled thousands of feet with core-shot ropes. We returned to base camp and crawled into the tent just as the skies unleashed.

We endured the storm contentedly, in disbelief at all we had just experienced. Our tent was sinking into the glacier, pulling the roof close to our faces. The glacier shuddered, making ominous pops and growls. Wind and ice hissed against the walls. Mere millimeters of synthetic fabric and a pile of down feathers kept us sheltered from the harsh elements. When the storm cleared, we hiked off the glacier and into the valley, elated to see signs of life and thaw in the warmth of the sun.

The comedown from such an intense experience unfolded in stages. I returned to Yosemite with no motivation to climb. Soon after arriving, someone close to me passed away in a climbing accident. Downloading from the expedition while processing the sudden loss was intensely jarring. I was reminded once again that nothing lasts forever. The more I reflect on the name we chose for our route on Asgard, the more it seems appropriate. We are fragile creatures. We ought to make the most of every moment in this life while we ever so briefly have it.

The epigraph of the Insight Meditation book Brandon carried with him offers a short poem by the Chinese poet Li Bai. We spent much time pondering its significance in the cramped quarters of our tent during the storms, peering through the vestibule to steal glances at Asgard. I find it very fitting:

The birds have vanished down the sky.

Now the last cloud drains away.

We sit together, the mountain and me,

until only the mountain remains.

SUMMARY: Three new routes in Auyuittuq National Park, Baffin Island, Nunavut, Canada, by Brandon Adams, Miles Fullman, and Sam Stuckey (all USA). First ascent of Ragnarok (2,500’, VI 5.11 A5), on the west face of Frigga I, July 16–20, 2024; the route ends at the ridgeline above the face. New route Fenrir (4,500’, with 1,500’ new, V 5.11 A2) on the east face of Mt. Loki, August 1, after fixing three pitches. First ascent of Memento Mori (3,600’, VI 5.10 A5), west face of the south tower of Mt. Asgard, August 4–8, after fixing two pitches. Topos for these routes are at the AAJ website. An interview with all three climbers is on the Cutting Edge podcast.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Miles Fullman calls Yosemite Valley home. A lover of mountains and books, he says climbing for him is a literary pursuit and an integral aspect of his quixotic journey of self-realization.