Ashat Adventures: Two New Routes in the Pamir Alai

Kyrgyzstan, Pamir Alai, Ashat Gorge

For a long time, I had been obsessed with climbing the north face of formidable Sabakh (5,300m), the crown jewel of the Ashat Wall, west of the better-known Karavshin valleys in the Pamir Alai. Over the years, I’ve amassed a collection of splendid blunders, and I count myself fortunate that this year’s escapade didn’t add to the list. With the Ashat Wall as the goal, our all-female team of Anastasia (Nastya) Kozlova, Darya (Dasha) Serupova, and I had won a Grit & Rock Expedition Award, which aims to support women on first ascents and other exploratory adventures. However, the three of us decided to give the treacherous, avalanche-prone Sabakh a wide berth. Instead, we set our sights on the beautiful but decidedly less perilous Parus West and Argo peaks.

In July, the three of us, along with Denis Prokofiev, the coach of the Krasnoyarsk women’s mountaineering team and our adviser, hopped on a plane to Osh, a vibrant city teeming with people and cows, with a bustling marketplace that never seems to close. From there we embarked on a full day’s road journey to the village of Uzgurush. Upon arrival, we loaded 200 kilograms of equipment and provisions onto donkeys and horses, and the real fun began—a two-day hike through rugged terrain. When the horse wranglers left, we were completely alone in the wilderness.

The mountains were draped in fresh snow. We waited patiently for two days, giving the faces a chance to shed their icy cloaks. We established base camp about two to three hours from the Ashat Wall, near a reliable water source. Our advanced base camp (ABC) would be just a 40-minute trek away, the perfect staging ground for our main objective: the north face of Argo.

First, though, Nastya, Dasha, and I decided to warm up and acclimatize on a logical line up a giant dihedral on the southwest face of the rocky Parus West (4,850m), which really looks like the “sail” for which it is named on the side we would climb. The terrain looked promising, with beautiful granite. On July 15, after approaching the wall and checking out conditions, we decided to start climbing late that same afternoon and we bivouacked low on the face.

The next day, Dasha took the lead, and we confidently made progress, climbing excellent rock pitches. However, it soon became evident that Parus wasn’t as rocky as advertised. The final sections were packed with snow and ice, and we’d left our ice tools and crampons in base camp. I found myself leading ice and mixed terrain with nothing but a rock hammer, which I had to use to carve steps in the hard snow and ice for about 100 meters. This was either incredibly innovative climbing or a nod to the early climbing trailblazers—certainly not a lack of planning or foresight!

We bivouacked midway up the wall, sitting on our packs and the rope, and then again near the summit. Starting down on the morning of July 18, we stumbled upon the belay anchors left in 2012 by Yury Koshelenko and Vasily Kolisnyk on the south-southwest buttress, and we used two of them that were in good condition.

While I was rappelling and searching for a spot to set up an anchor, I noticed a rock the size of a melon hurtling down from above. I was about to shout “Nice try, but you missed!” when it didn’t, smacking my hand. I howled in frustration as we continued down, either from the useless painkillers or from the thought that we might not be able to climb Argo. Luckily, my hand wasn’t broken, just bruised and bloodied.

All in all, our route had been an ideal warm-up, designed to fool us into thinking that the ascent of Argo (4,750m) would be a breeze. For a couple of days, we gorged on food—borscht, stew, and so on—rolling from one plate to another, and at the same time we managed to sort through the equipment and stuff it back into the packs, preparing for our main objective.

The first time we saw Argo and the Ashat Wall, during a reconnaissance, they were completely covered with snow and the wall looked huge, powerful, harsh, amazing. Thinking of the legends who had climbed here before was intimidating.

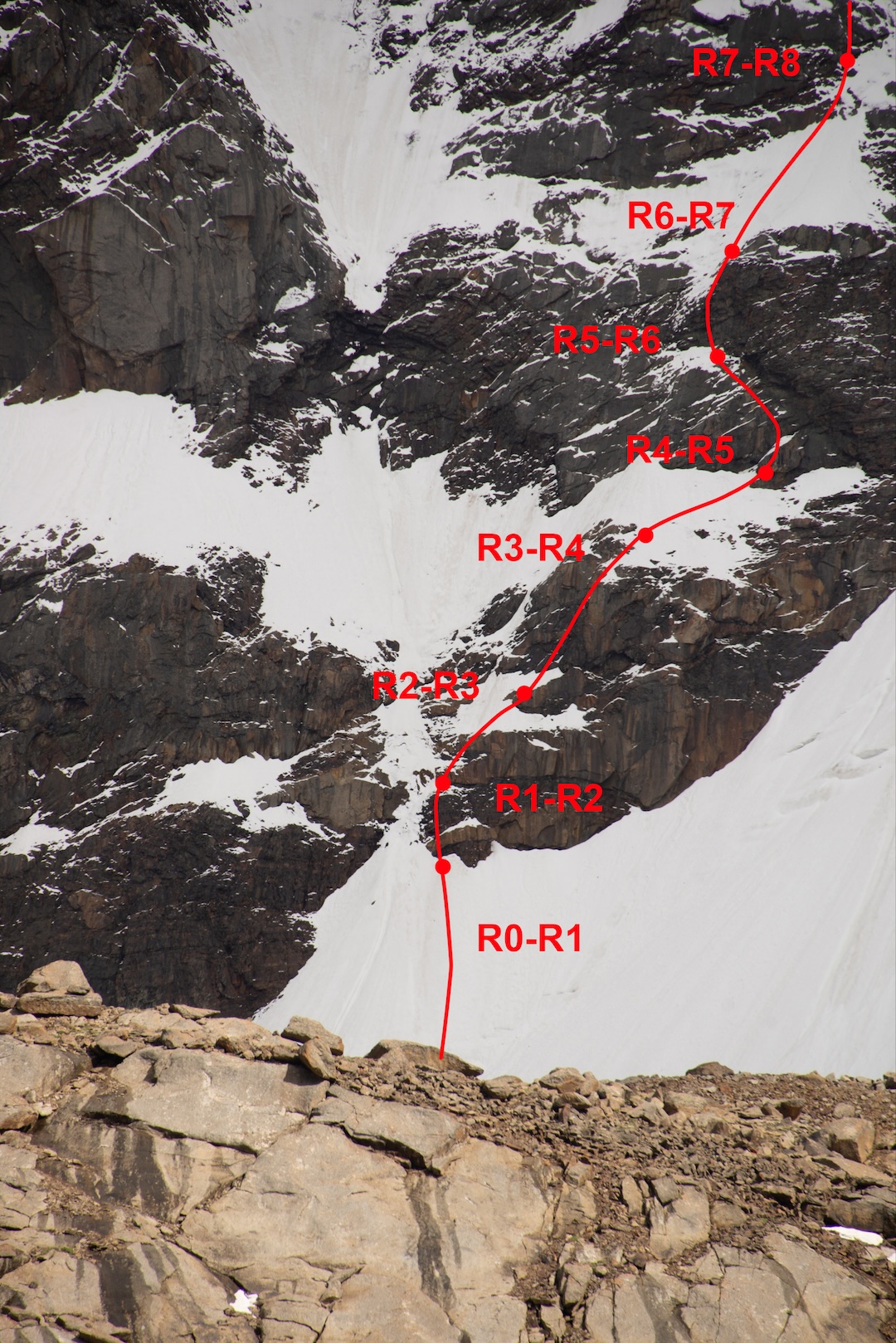

After our second approach, we discovered that the ice runnels in the center of Argo’s north face were about to melt; our intended route essentially did not exist. Fortunately, we found some ice on the far right side of the wall, to the right of the Petrov Route (1989, 6A), one of two existing routes on the face.

On July 22, we started up an ice gully (which had completely melted out by day five as we rappelled down). The warmth made the ice unstable and sketchy, so I opted for mixed climbing, even though the ice would have been quicker and easier to climb. The three screws I placed in the rotten ice were just for my sanity. Nonetheless, we managed to gain the first 500 meters—nearly half the route—quite quickly, completing it in one day.

The second half of the wall became significantly steeper. The main challenges? Oh, just the usual: slippery, ice-filled cracks, loose rock and rockfall hazards, and weather that seemed to think it was auditioning for a disaster movie, with frequent thunderstorms, hail, and snowfall. Hauling our heavy equipment was a real endurance test. As if that weren’t enough, we had brought a well-worn portaledge that clearly was designed to test our willpower and sense of humor. Without these, the daily two-hour wrestling match to assemble the ledge would have been unbearable.

A storm was forecast for our second day on the route, and our plan was to ride out the storm but still try to make a little progress. While my two climbing partners battled through a few pitches, the sky darkened and hail and snow began to fall. I stayed behind to guard the house, eating everything I could reach and rolling from side to side to appear busy.

The next two days were intense, pushing us to 7b (French) on the rock. Nastya tackled an incredible frozen chimney with fearless precision. Dasha took on a stunning wide crack stretching several pitches; these ideally would have been protected with a number 6 Camalot, but since we had only a single number 4, protecting this crack turned into a thrilling exercise in creativity with chockstones and other features. At one point, we ended up on a full rope length of vertical scree—huge, disconnected blocks where removing a piece of protection might trigger a cascade of failure, possibly damaging the rope. I felt a tremendous relief at having overcome this demanding aid section (up to A3+).

On July 25, we reached the saddle between Argo and Svarog, with a stunning view into the mountains of Tajikistan. We set up the portaledge there and decided to go for the summit right away, leaving behind the ledge, sleeping bags, and other gear. The upper west ridge had enjoyable climbing, passing pillars of granite interspersed with mixed climbing. After four more pitches, we reached the top and then descended back to the saddle for our fourth bivouac.

Rappelling from the saddle went smoothly—the ropes didn’t get stuck even once. There were many free-hanging rappels, which, with heavy packs, became excellent exercises for the core and back muscles. At the last anchor, we unclipped the portaledge and watched as it limply bounced and rolled down the slope. The three of us relished the spectacle, savoring a blissful moment of sweet revenge.

Returning to base camp after five days on the wall felt like coming home after months away. We recalled the lively debates at the end of our first day on the rotten ice—whether to rappel or to continue up. Now we felt drained yet delighted. I have no doubt these are landmark routes for the three of us, and we’ll remember this trip as a significant turning point. As for where this will lead us, well, we will see.

SUMMARY: Two new routes in the Ashat Gorge, Pamir Alai, Kyrgyzstan, by Anastasia Kozlova, Olga Lukashenko, and Darya Serupova from Russia—these were the first climbs by a women’s team in this valley.

The trio first climbed the southwest face of Parus West (4,850m), July 15–18, 2024. Their new route was graded Russian 5B (ED- 6c M3 A2), with 28 pitches and 1,460 meters of climbing distance (1,150m vertical). They rappelled the south-southwest buttress.

From July 22 to 26, they completed a new route on the north face of Argo (4,750m), to the right of the Petrov Route (1989, 6A) and completely independent of that line. The 29-pitch route gained 950 meters, with 1,250 meters of climbing, and was rated Russian 6A (ED 7b M5 A3+). They descended the climbing route, placing two bolts for rappel anchors. No bolts were placed during the ascents.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Educated in Russia and Switzerland, Olga Lukashenko lives in Germany and France while working full-time in information technology for a Czech company. Adding to her overflowing plate, she’s training to become an IFMGA guide.