Headstrap; Alpine Rising

By Nandini Purandare and Deepa Balsavar, and by Bernadette McDonald

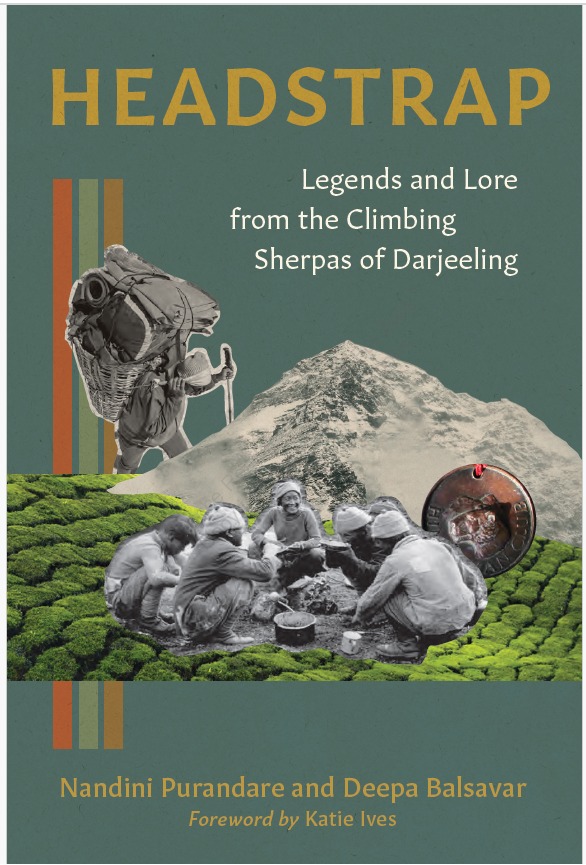

Headstrap: Legends and Lore from the Climbing Sherpas of Darjeeling. By Nandini Purandare and Deepa Balsavar (Mountaineers Books).

Headstrap: Legends and Lore from the Climbing Sherpas of Darjeeling. By Nandini Purandare and Deepa Balsavar (Mountaineers Books).

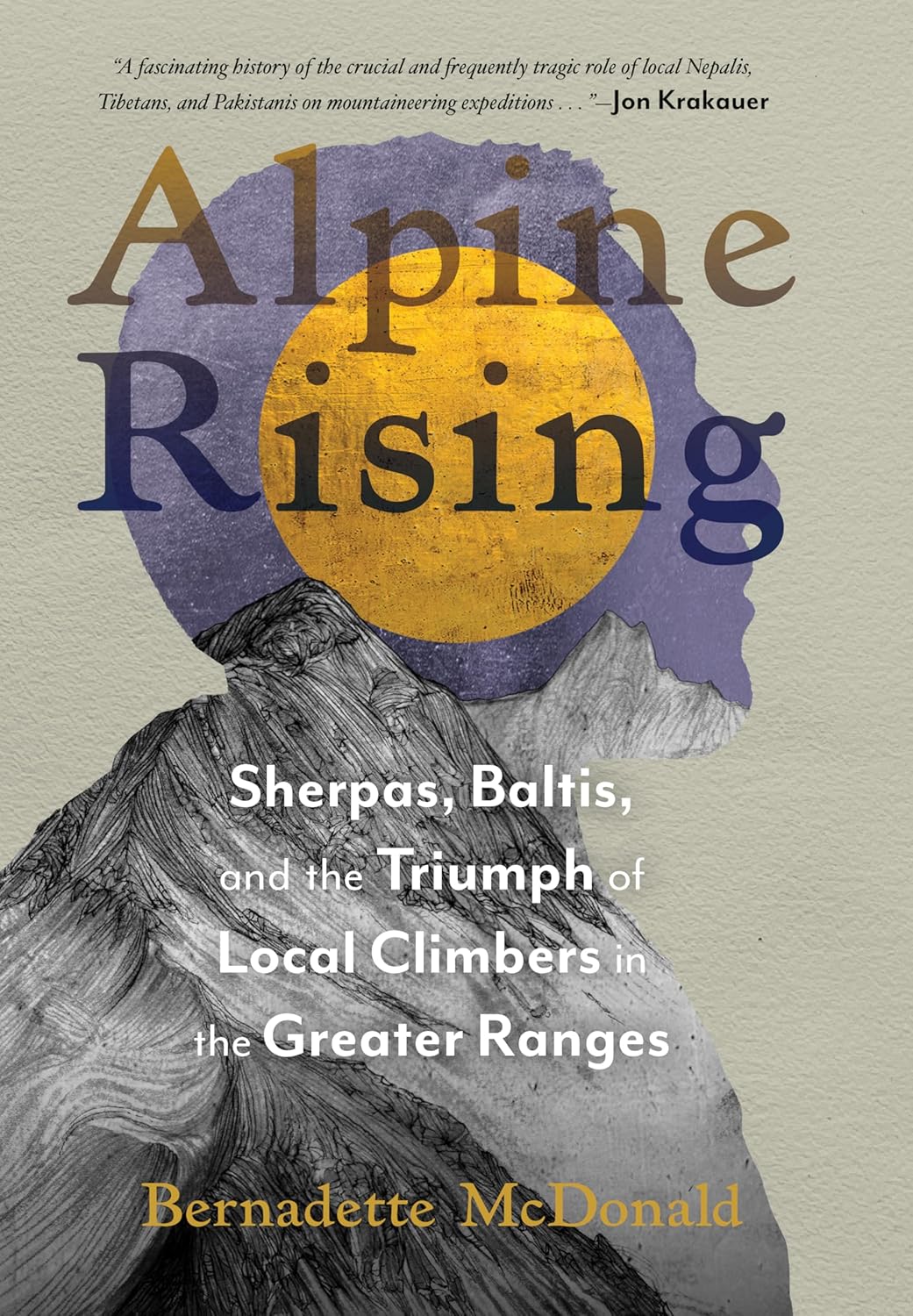

Alpine Rising: Sherpas, Baltis, and the Triumph of Local Climbers in the Greater Ranges. By Bernadette McDonald (Mountaineers Books).

I have been waiting for these books all my life. As someone whose every school-age vacation was spent walking in the Bengal/Sikkim/Garhwal/Kumaon Himalaya and as an absurd girl who tried to read everything she could lay hands on, I desperately wished, even as I read extraordinary books by extraordinary mountaineers from around the world, that I had greater access to the stories of the people whose food, music, architectures, languages, religions, color palettes, and ethics composed my days.

The very few indigenous narratives that existed—Tenzing Norgay’s or Ang Tharkay’s, for example, notwithstanding their mediation by translators and co-authors—seemed like exceptions proving the apparent rule that mountaineering ambitions, innovations, and accomplishments were the proper domain of white and usually male climbers. And that mountaineering was a proper exercise of the colonial drive: that human beings naturally relate to mountain landscapes with a sense of entitlement and dominion.

The backbone of all Himalayan mountaineering that has ever existed—who carried the food and fuel infrastructure; who cooked; who ran the communications on foot; who provided the rescues—was in plain view for me but missing from the literature. Evidence countering the notion of humans’ colonial engagement with mountain landscapes was similarly in plain view: People were giving birth and bringing up children; grieving losses; striving for better conditions; learning generational ways; nurturing the land; building schools; teaching even my little sister and me to take only what we needed; training us to think “like glaciers” so that we could walk safely on them; and much more. But from the “great” 20th-century mountaineering books, you would not know.

Despite its subtitle lightly evoking “legends and lore,” Nandini Purandare and Deepa Balsavar’s Headstrap is based on solid archival research: painstaking perusal of nearly 100 years of Himalayan Club records, hundreds of hours of conversation in over 150 interviews, and, importantly, a decade of thinking and writing by two remarkable storytellers. Headstrap is an uncovering of some of the complexities, dreams, fallibilities, leadership, and sheer grit of the single most influential demographic of climbers in the highest mountains of our planet. Here, some of the greatest legends of mountaineering—Ang Tharkay, Pasang Dawa Lama, Ang Tsering, and Tenzing Norgay—emerge as people with their own profound realities of needs; explained and unexplained ambitions; camaraderies of the trail; heroisms and lapses of extenuating circumstances; glories of recognition; lonelinesses of success; and dreams of better futures for their children.

Structurally, the book situates the cultural history of the climbing Bhutias, especially Sherpas, of Darjeeling in three parts, usefully ranging from 1) the 19th century’s imperial Trigonometrical Survey of India (in the course of which a Bengali named Radhanath Sikdar first calculated the tallest mountain on Earth into record in 1852), to 2) the “Darjeeling dream” that brought so many inhabitants of Khumbu to Darjeeling with the promise of employment throughout the 20th century, to 3) post-independence neocolonialism that continues to beset mountaineering in the subcontinent today. This political history of the region is well known but has seldom been so succinctly rendered. More valuably, this story has never been told with clear exposition of the colonialist-capitalist underpinnings of all the botany, anthropology, geology, commerce, medicine, and “development” in the area.

There is also a meta-critical awareness with which Purandare and Balsavar exercise their listening (for theirs is ultimately an oral history) and then transfer it to the page so readers can hear these remarkable stories. The facts sometimes change between tellers. But—and perhaps therefore—the truth remains.

Dozens of unforgettable moments emerge, including, among many others: 1934, year of desolations on Nanga Parbat, when Joan Townend, then secretary of the Himalayan Club, realizes the importance of creating meaningful records of Darjeeling’s “for hire” climbers; 1945, when Ang Lhamu agrees to marry her late cousin’s husband, Tenzing Norgay, and to look after his two young daughters; 1945, when Ani Lhakpa Diki “waits and waits” for her partner to return from a reconnaissance expedition to Kangchenjunga and is finally given $36 as compensation for her husband, then leaves her nine-month-old in the care of her three-year-old while she puts her load-carrying headstrap back on to earn subsistence for the family; and ca 1976, when Ongmu Gombu is dropped off for her first day at school by her father, Nawang Gombu, for whom this simple parental activity becomes a “big thing” because “he didn’t go to school.”

The book also tells the story of post-colonial (with the hyphen in the sense of after colonialism) Darjeeling climbing. The creation of the Himalayan Mountaineering Institute was famously facilitated by Nehru, the first prime minister of India, following the success of Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay and capitalizing on interest in mountaineering in 1954: “The Institute trains young men not only to climb Himalayan peaks, but also creates in them an urge to climb peaks of human endeavor.” With its express emphasis on “young men”—a curious emphasis in a democracy otherwise aspiring toward such equality that universal adult suffrage was enacted in 1949, a mere two years after political independence in 1947—the Institute relegated itself to being a future boys’ club. And with its first—and every subsequent—principal being a member of the military, the Institute similarly constrained itself to assault-oriented stagnations of the art of climbing.

The same despicable colonial drive that made of Chomolungma (as the mountain was known by Bhutias) or Sagarmatha (as it was known by the Nepalese) an “Everest” (so named after an imperial surveyor who never set eyes on the mountain) similarly kept the stories of some of the world’s most accomplished climbers as a footnote of sorts in mountaineering history for over a century. Purandare and Balsavar’s book goes a terrific way toward balancing the record. But a longer way yet remains for these very important stories to be told as fully or as contextually as possible. Among the things that should come next is the trove of mountaineering history that Bhutias and Sherpas themselves carry, and which, should they choose to share in their own voice, we should read with care.

Until then, this book should be required reading for all visitors to the Himalaya, just as the first action items incumbent upon everyone even thinking of climbing in the area should be to 1) somehow contribute to better maternal and infant care in the area and 2) contribute to better insurance for Himalayan climbers and support staff.

Meanwhile, the Himalayan Club will be 100 years old in 2028. The importance of this organization for historically aware Himalayan studies of any stripe cannot be overstated. It is time for a critical history of this colonially established organization that has finally begun something of its postcolonial (without the hyphen, in the sense of critical of colonialism in all its forms) evolution that may keep it relevant for the next 100 years. Perhaps these authors—one of whom is president of the Club and editor of the Himalayan Journal—might take up the work.

Meanwhile, the Himalayan Club will be 100 years old in 2028. The importance of this organization for historically aware Himalayan studies of any stripe cannot be overstated. It is time for a critical history of this colonially established organization that has finally begun something of its postcolonial (without the hyphen, in the sense of critical of colonialism in all its forms) evolution that may keep it relevant for the next 100 years. Perhaps these authors—one of whom is president of the Club and editor of the Himalayan Journal—might take up the work.

With Alpine Rising, Bernadette McDonald continues her transformative contribution to mountaineering literature in the 21st century. Rich in another set of interviews—so much so that the interviewers and translators Saqlain Muhammad and Sareena Rai arguably function as authorial collaborators for this volume—McDonald’s book does characteristically vivid and meticulous work of bringing the motivations, dreams, losses, flamboyances, and achievements of “local” climbers to light. With less cohesion but with ample detail, this book also tells the story from the beginnings of Himalayan mountaineering to this day. In McDonald’s clear writing, stories of two distinct communities of climbers—of the Nepalese/Indian/Tibetan Himalaya and the Karakoram, respectively—emerge in conversation with one another.

Valuably, this is one of the first books in English to document stories of certain Karakoram climbers from the earlier 20th century—starting with the first Nanga Parbat expedition in 1932—to the present. The author, who brought us the magnificent Freedom Climbers (2011), again brings to narrative an entire community of mountaineers whose political and socio-economic realities condition their climbing. This time, the story feels unfinished. I dare to hope this is because McDonald’s next project is a history of Pakistani climbing, especially in the Karakoram.

The book’s greatest achievement is in McDonald’s willingness and ability to demonstrate the distance between the very planets that Himalayan mountaineering’s employers and employed hailed from throughout the 20th century. One of the most stunning stories is that of the egregious (non)leadership of Fritz Wiessner, who in 1939 managed to alienate and then lose track of most of his team on K2, and then also dispatched and lost a phenomenally strong rescue team—the upper reaches of the rescue being unconscionably, if unsurprisingly, composed solely of Sherpas. Three Sherpa climbers, Pasang Kitar, Pasang Kikuli, and Phinsoo Sherpa, were lost. None of the reports resulting from the expedition had time or space for the families of the Sherpas who died. And this is not the only story of vast discrepancies in outcomes.Notwithstanding the subtitle’s promise of tales of “Triumph of Local Climbers in the Greater Ranges,” the book holds necessary space for the sufferings, non-recognitions, griefs, and continued prayers of the climbers who gave so much of themselves to the high mountains, and those of their partners and children who still hold the vast emptiness of the losses.

A remarkable high point rounds out the story of the triumphs: the winter ascent of K2 by ten Nepalese climbers in 2021. Rightly, that story has been and continues to be told mainly by its protagonists. What is ultimately at stake, McDonald reminds us, drawing on Tashi Sherpa’s words, is respect. “The mountains are about mutual respect,” Tashi Sherpa says. And “climbers from Nepal and Pakistan deserve all the respect they are finally getting,” writes McDonald. “Respect is worth celebrating.”

—Amrita Dhar