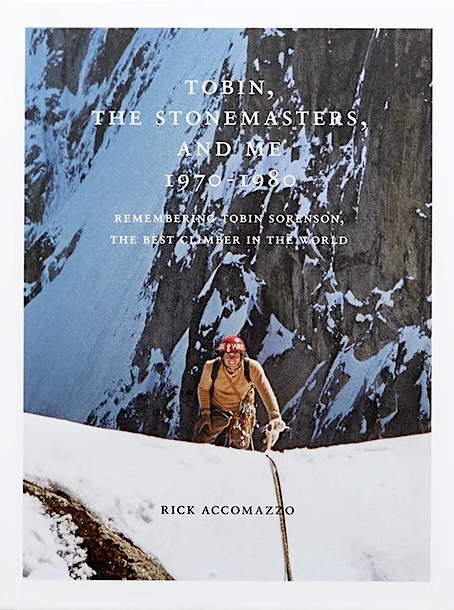

Tobin, the Stonemasters, and Me, 1970–1980: Remembering Tobin Sorenson, the Best Climber in the World

By Rick Accomazzo

Tobin, the Stonemasters, and Me, 1970–1980: Remembering Tobin Sorenson, the Best Climber in the World. By Rick Accomazzo (Stonemaster Books).

Tobin, the Stonemasters, and Me, 1970–1980: Remembering Tobin Sorenson, the Best Climber in the World. By Rick Accomazzo (Stonemaster Books).

Much the way nature abhors a vacuum, historians seem to hate unlabeled epochs. A chunk of American climbing history seems to have been left without a title. It’s the bit between the end of the “Golden Years” (roughly the mid-1950s through the late ’60s) and the time since sport climbing took over in the mid-1980s. That is, the period from about 1970 to roughly 1983–84.

Though unnamed, this was certainly an important period in climbing history, and it was characterized by some of the most impressive ascents that ever happened in the Western Hemisphere—hard free climbing, sketchy protection, and very limited use of permanent anchors. It melded with the hippie music and the dropout motif of the day—and the incredible amounts of drugs being consumed.

These guys and gals (the guys were numerous; the gals few—folks like Lynn Hill and Mari Gingery) did things their own way and pointed the way forward. Somehow, sport climbing subverted what should have been hard traditional free climbing’s brilliant adulthood—hard trad would take a hit for several decades. (Though it’s been revived, thankfully.) In the 1970s and early ’80s, the guys and gals pushing the sport called themselves the Stonemasters, and their influence was felt not just in California but all over the continent.

Now, Rick Accomazzo, a central figure of the Stonemasters (these days a retired lawyer in Boulder), has written a book describing his life with that group and the life of Tobin Sorenson.

Compared with his Southern California brethren (a band of well-meaning misfits), Tobin Sorenson was a different egg. His life was anchored to religion. He swore off drugs and alcohol (he thought beer “taste[d] like piss”), and he climbed in the name of the Lord. In the early 1970s, he blitzed through Southern California, then Yosemite, setting a high bar with nearly every climb. Then he got into alpinism and rocked the world.

Accomazzo sums up his case for labeling Sorenson “the best climber in the world” at the end of the 1970s: “In the span of one year, starting in August 1977, after a long layoff, he climbed the hardest Alpine walls in Europe, putting up four new routes (including two on the fabled great north faces), the first alpine-style ascent of the Eiger Direct, and the third winter solo of the Matterhorn north face…. He had climbed the hardest Yosemite routes in near-perfect style at a time when Yosemite Valley contained the most difficult rock climbs in the world. Finally, in the same year, he dipped his toe into high-altitude climbing and succeeded in a bold, on-sight free solo ascent of 20,981-foot Huandoy Norte. In the next two years he bounced from daunting first winter ascents in Canada, to first ascents on sunny Australian cliffs that surpassed the existing grades, to impressive technical alpine first ascents in New Zealand.”

One of the best things about Tobin, the Stonemasters, and Me is how it shows the huge influence Southern California (specifically Tahquitz) had on climbing in Yosemite Valley. After all, the “Yosemite” decimal system was invented at Tahquitz, as were many other climbing ideas and styles, and certainly many of Yosemite’s best climbers—including Sorenson—cut their teeth at Tahquitz.

The Stonemasters meticulously explored Southern California, then came to Yosemite and changed the game in free climbing and the notions of speed, style, and boldness. There’s a reason Jim Bridwell, John Long, and Billy Westbay stand so proud in the famous photo of them in front of El Cap—they earned it. Indeed, there’s a reason the Stonemasters’ logo—a lightning bolt adopted from Gerry Lopez’s line of clothing, jewelry, and surfboards—gets rescrawled on the Midnight Lightning boulder problem every year. You have to be a master of stone to do the problem.

In recounting Stonemasters lore, Accomazzo’s fine work belongs alongside a couple of other books—George Meyers’s Yosemite Climber (1979) and John Long and Dean Fidelman’s The Stonemasters: California Rock Climbers in the Seventies (2009)—and it does worthy service to anyone wanting to label that magical epoch by describing the playgrounds and, more importantly, the players.

Tobin, the Stonemasters, and Me is one of the best reads I’ve had in a long time, and it puts the shine on what it means to be a climber. And—a nod to the designer—it’s a beautiful book to hold and behold: gorgeously designed, wonderfully illustrated, sumptuously packaged. They put some ducats into this one.

Go with the flow, man, and embrace the style, the boldness, and the sheer thrill of the Stonemasters era.

—Cameron M. Burns