Pico Bolívar, West-Northwest Rib

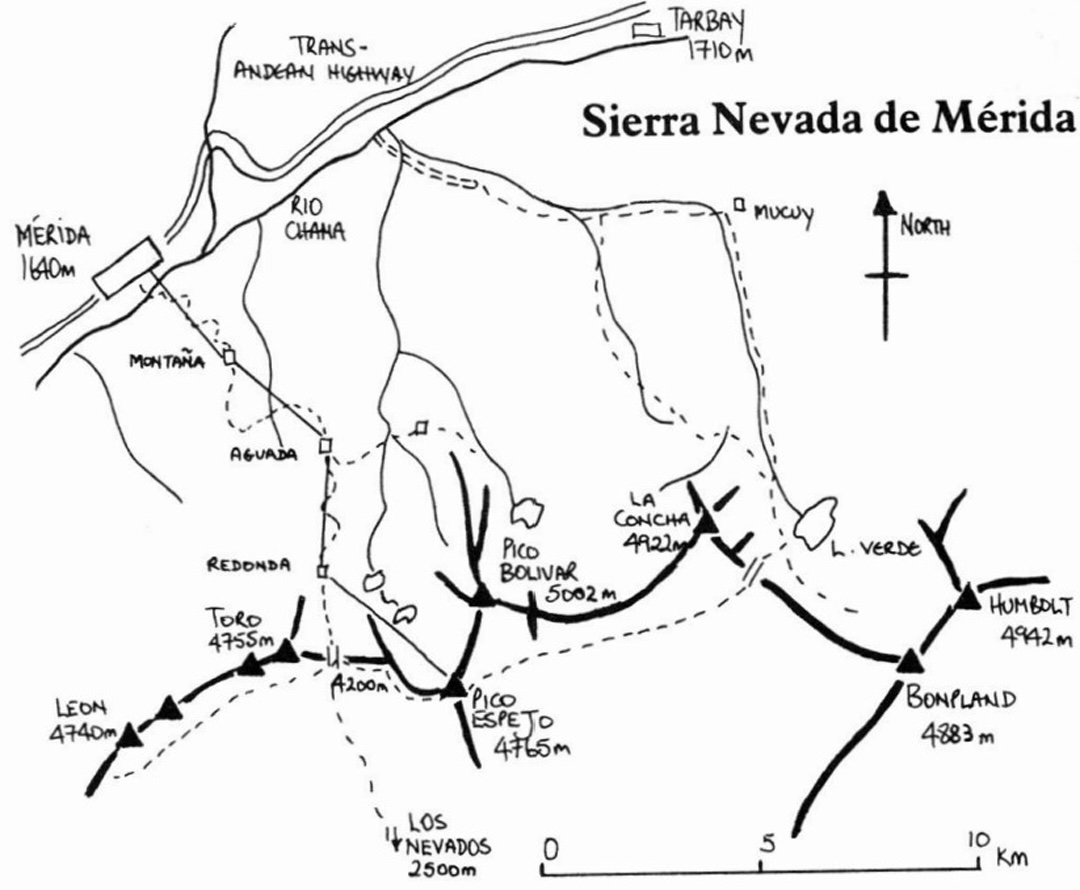

Venezuela, Sierra Nevada de Mérida

For Jan Solov and I to attempt a new route on a 5,000m South American peak in a 13-day round trip from Britain would require all the elements of easy access, predictable weather (if such a thing exists), a considerable amount of luck, and strong analgesics to combat the thumping headaches resulting from inadequate acclimatization. The Sierra Nevada de Mérida possessed the first two properties, and an adequate supply of 500mg Parahypon the last.

The town of Mérida, situated to the north of the range, had a dearth of picturesque colonial architecture. In fact, in late December 1985, there appeared little to attract even Venezuelan tourists to this reputedly chilly town surrounded by a jungle of coffee and banana plantations—little, that is, except for the teleférico.

In four consecutive stages, the world's longest and highest cable railway reaches the 4,750m summit of Pico Espejo on the main crest of the range. Bottled oxygen plus a doctor must always be present at the top station when the lift is operating. During peak holidays, 400 or more make the return journey daily to gaze at the glaciers and rock walls of the country’s highest mountains—snow being a rather unusual commodity in Venezuela.

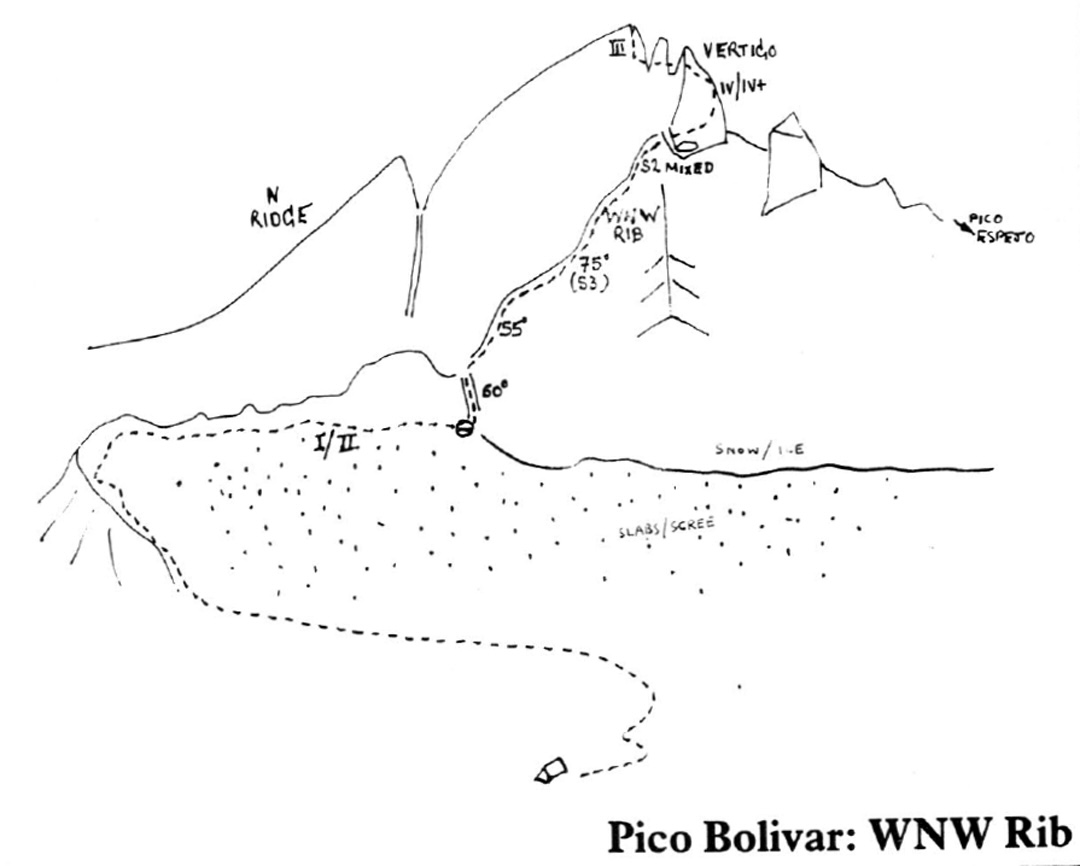

Pico Bolívar, then pegged at 5,007m but today reassessed at 4,978m, is the point of highest uplift in the Sierra Nevada de Mérida. The first confirmed ascent to the very top is credited to Fritz Weiss in 1936 via an arduous approach from the south. (However, it may have been reached by Venezuelans a year or two previously.) Our research indicated the west-northwest rib was an elegant line that had not been climbed in its entirety. A garishly painted papier mâché model of the Pico, contained in a glass cabinet at the teleférico entrance, implied we ought to disembark at Lomo Redonda (4,045m), the penultimate station, then walk south a kilometer or two to the lakes of the Pico Espejo Valley.

The upper valley marks the altitude limit for equatorial growth, and we attempted to hide our bright red tent beneath the branches of a solitary tree. On the ground there was no trace of any human visitation, yet surreally, way above our heads, people drifted noiselessly to the summit station of the cable car. The next 24 hours were spent in anguish that even the magic Parahypon was unable to subdue, but normal service was resumed after the second night and, burying our tent and remaining valuables as a safety precaution, we left with three days of food.

The lower section of the spur would have given pleasant scrambling, with a few graded pitches, for fit, unladen individuals. We were neither. The rock wasn’t bad, even if most parts appeared to be held in place by a very furry lichen. Equatorial sunsets are always “staggeringly beautiful” and ours was no exception, viewed from a bivouac before the first snow on the spur.

Dawn was cold and the initial couloir moderately steep. The spur comprised a series of crisp snowy steps, a rocky buttress, and a narrow upper section. Snow and ice conditions were as perfect as one could imagine. An unavoidable icy gully through the buttress gave the hardest pitch, though no more than Scottish 3. Final access to the upper southwest ridge was barred by a pointed gendarme, Pico Vertigo. Difficult climbing involving a little aid on rotten rock led to a shoulder some 40m or so below the top.

Steep, loose granite guarded the way to a fine knife-edge, and I wasted an hour before deciding that rock shoes rather than plastic boots, more gear than our half dozen runners, and a longer neck would be, for me at least, a necessity to climb that pitch. A diagonal abseil took us on to a small glacier shelf, where we settled in for another “staggeringly beautiful” sunset and a liberal dose of Parahypon.

The next day, December 29, we climbed two pitches to the southwest ridge, which, though easier than those on Vertigo, were probably more dangerous. It was with relief that we traversed the sharp summit ridge on commendable solidity to reach the top of the mountain, where an enormous bronze bust of Simón Bolívar looked down with disdain.

We descended south and reached the shrunken Timoncito Glacier before dark. As it was Christmas weekend, several lights winked from beneath giant boulders as we crossed moraine to the glacial river, where we bedded down for the night. Next morning, we traversed to Pico Espejo on a surprisingly easy path. On arrival, our solitude was shattered by seemingly half the population of Venezuela, and their various animals, playing on the 400 square meters of snow encircling the summit station.

Two days later, we had moved all our gear to a salubrious hut at Lomo Redonda. The following morning, Jan elected to celebrate a rather quiet New Year’s Day curled up with the station’s least bothered guard dog—his mate had bolted on our arrival—while I made a crossing of the Toro-León massif. It proved an absolute classic ridge traverse on the best granite imaginable: seven kilometers of sharp, airy, and exposed scrambling with a few more difficult pitches. The flanks appeared to offer considerable scope for short but technically demanding new routes.

On the flight back to Caracas, our pilot—ostensibly for our benefit but also, I suspect, to impress his aviation skills on the audience—made a double circuit of the Sierra Nevada at close quarters. There were obvious challenges for a future visit, not least the mega traverse of the entire range from León to Humboldt. However, there are too many enticing unfrequented gems in the corners of our planet, and for us Mérida would become a highly memorable yet one-off adventure.

—Lindsay Griffin, U.K.