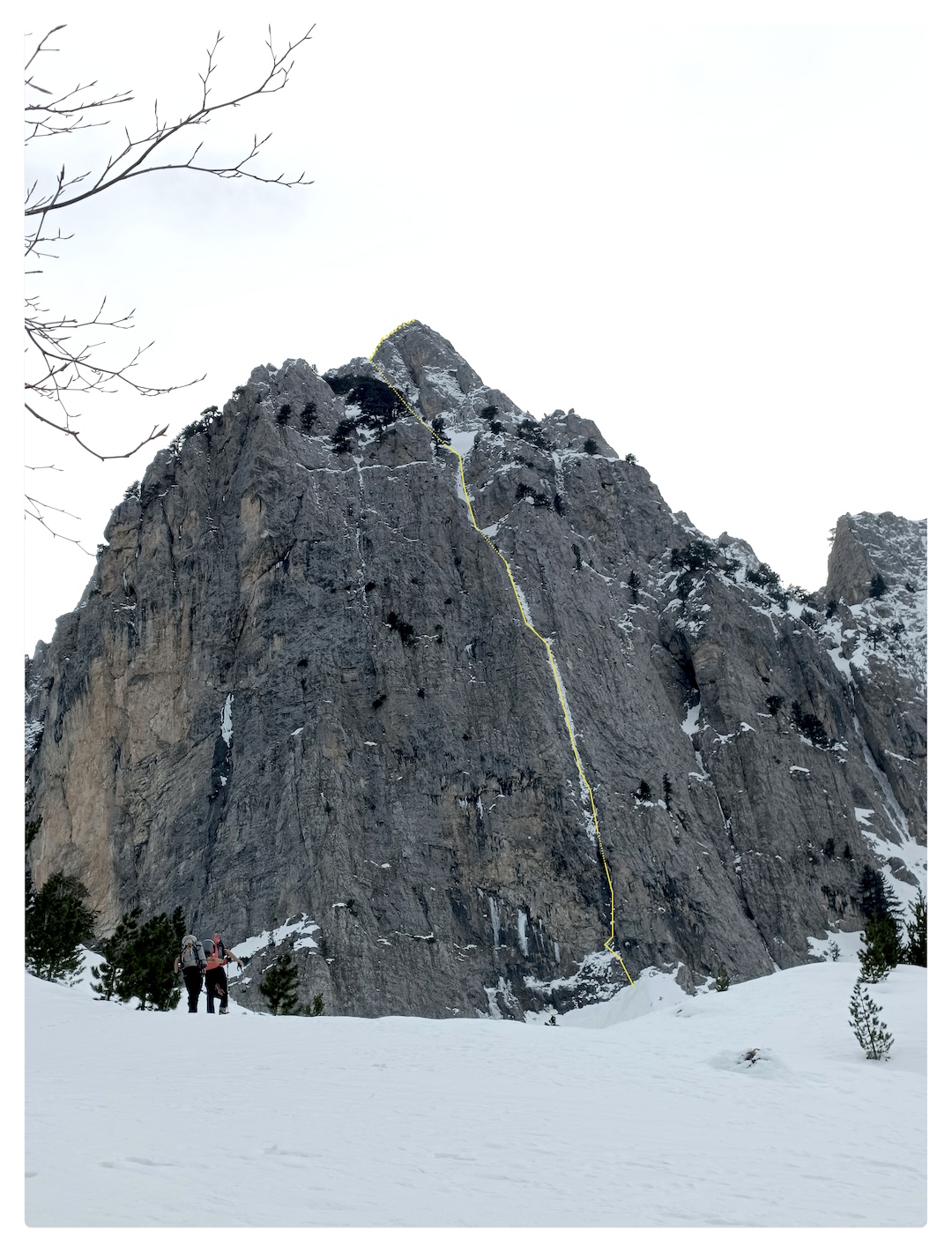

Tsouka Rossa, Scream of the Butterfly, Winter Ascent

Greece, Epirus Region, Pindus Mountains, Tymfi Massif

February 10, 2024, 6 p.m. After 12 hours of demanding climbing, nightfall and a killer wind caught us on the northeast spur of Tsouka Rossa (2,377m) in the Pindus Mountains while we searched for the easiest way through a labyrinth of mixed terrain. In the end, Dimitris Daskalakis, Christos Tsoutsias, and I would need six more hours to reach the summit and complete one of the “most wanted” alpine ascents in Greece: the first winter ascent (FWA) of the summer rock route Ourliahto tis petaloudas (Scream of the Butterfly, VII-/5.10, 300m in summer, 500m in winter with the northeast spur, Kallos-Rokas, 1993).

The Pindus are the backbone of Greece, running about 140 miles through the western part of the mainland, stretching from the Korytsa Plateau (southeast Albania) to the north side of the Peloponnesian peninsula. Tsouka Rossa is among the most imposing features in the range. Located in the Tymfi Massif, Tsouka Rossa’s limestone north walls stand 500m tall. This impressive formation is isolated, with approaches from three to five hours and tough descents, away from huts or lifts and any possibility of rapid rescue.

Greece is a warm, maritime country, and the typically unfavorable winter conditions have taught us to deal with whatever the season brings for alpine climbing. Yet, the tradition of winter alpinism dates back to the 1960s. According to G. Voutyropoulos, C. Belogiannis, and A. Asimakopoulos’s guidebook Alpine Climbing in Greece (2022), winter alpine climbing solidified in the ’70s, thanks mainly to leading climbers D. Korres and D. Boudolas, who made a push for the FWAs of summer rock routes on the big headwalls of the Greek massifs, following the most obvious lines; their “alpine” style involved using ice tools for snow-covered terrain but boots and bare hands for dry rock. Some of the most important ascents from that period include the Via Arvanitidis-Galinos-Kasimatis (900m, IV 3 M2) and Via Korres-Tsourtis-Booth (900m, IV 3 M3) on the peak of Neraidorahi Northeast (2,340m), or the FWA of Emilio Comici’s summer route on the east face of Stefani Peak on Mt. Olympus (2,918m), by D. Boudolas and E. Tosidi.

Starting in the late 1990s, Greek alpinists began exploring thin ice runnels and modern mixed faces on many of the Pindus massifs. The year 1998 saw an FWA of pivotal importance in the Vardousia Massif. There, the trio of C. Bellogianis, D. Bourazanis, and N. Hatzis followed a steep ice runnel using modern mixed techniques; their route, Paranoid Androids (200m, III+ 4 M4 A1), would radically alter the direction of Greek alpinism. After that, each year saw standards being pushed, with the high point being the adventurous FWAs of the late Y. Torelli and Y. Theoharopoulos in the Tzoumerka mountains (up to 2,429m on the summit of Kakarditsa). Icefalls form here when the weather is cold enough, with two major ice lines, White Conquest (850m, VI WI5+) and The Bow (600m, V WI6).

The Tymfi Massif remained less explored in winter compared with to the others, with its isolation, big north faces with stout routes, mediocre rock, and sparse protection, especially in winter. The earliest rock climbs on Tymfi had been established in the 1960s, but up until 2003, winter ascents here followed easy, low-angle gullies; however, that year, P. Athanasiadis and G. Voutyropoulos established the first true winter climb, on the north face (500m, TD) of Goura, a peak on the eastern part of Tymfi’s North Wall. In 2011, the same duo attempted another, seemingly more challenging line on the face’s central ramp, from which they retreated after four pitches because of bad conditions. In 2013, A. Karapetakos, G. Karnakis, and K. Karnakis made another coveted FWA, this one of the summer route Tsekouri (400m, III 4 M4) on the north face of Gamila, an impressive peak on the westernmost part of Tymfi’s North Wall. In 2018, T. Moutafis, Y. Torelli, and G. Voutyropoulos carried out another cutting-edge winter ascent, North Tsouka Rossa, this time on Tsouka Rossa’sthe eponymous formation’s north face (400m, AI5 M5).

Meanwhile, almost every winter, dead center on the north wall of Tsouka Rossa, Scream of the Butterfly froze into a thin ice runnel. This route—its poetic name taken from the Doors song “When the Music’s Over”—had captivated our alpine climbing community for the last 20 years. It had seen many failed attempts, due to bad luck and poor conditions, leading to near-mythical status as Greece’s most demanding alpine climb. Now, standing on our predecessors’ shoulders, we began to dream of our own attempt.

In February 2024, a photo of Tsouka Rossa showed it plastered with snow and ice. This was enough to lure me, along with Dimitris and Christos—two of the most talented climbers I know—for an attempt. Two days after seeing the photo, we were in the car to Tymfi. The plan was to make the three-hour approach, bivouac below the route, and, at first light, try our luck.

Dimitris undertook the first three pitches, which ended up being the driest and most difficult, with challenging dry-tooling, mediocre protection, and a wet, slick, narrow chimney on the third pitch that surely wasn’t meant to be climbed in winter. The terrain was very steep, making for slow going. For the next three pitches, up mediocre alpine ice, Christos took over, leading the heady terrain with true courage. It was now 6 p.m. and night had fallen. Even though we had completed the route’s steepest, most difficult section, we still had to climb up through the maze of Tsouka Rossa’s northeast spur.

Climbing by headlamp through strong winds, sometimes pitching out the terrain and sometimes simul-climbing, we reached the summit at midnight. After two rappels down the south face, we hugged with emotion, having completed a route that will be etched in our memories forever. Some five hours later—and after 23 hours on the go—we were back at the car, having completed the FWA of Scream of the Butterfly (500m, III AI5 M6+).

Winter climbing in Greece, even though it sounds improbable, really does exist—and right now it is enjoying some of its best days.

—Spyros Kyriakou, Greece