Rappelled Off Wrong End of Fixed Rope

Vermont, Wheeler Mountain, Practice Slab

On September 8, Alden Pellett (61) was bolting a new route on the smooth granite Practice Slab at Wheeler Mountain in northern Vermont. Pellett is a very experienced climber, with many first ascents in the Northeast.

Pellett wrote to ANAC:

“That morning, I rappelled from a tree to a flat dish, where one could easily stand. There I installed a two-bolt anchor on a route I had rehearsed on top-rope then soloed the year before. I drilled the anchor, equipped it with locking carabiners on a pre-tied quad, clipped in with a PAS, and then pulled my rope from the tree above. I was in a bit of a hurry. Weather was coming in, and I was eager to get the route installed.”

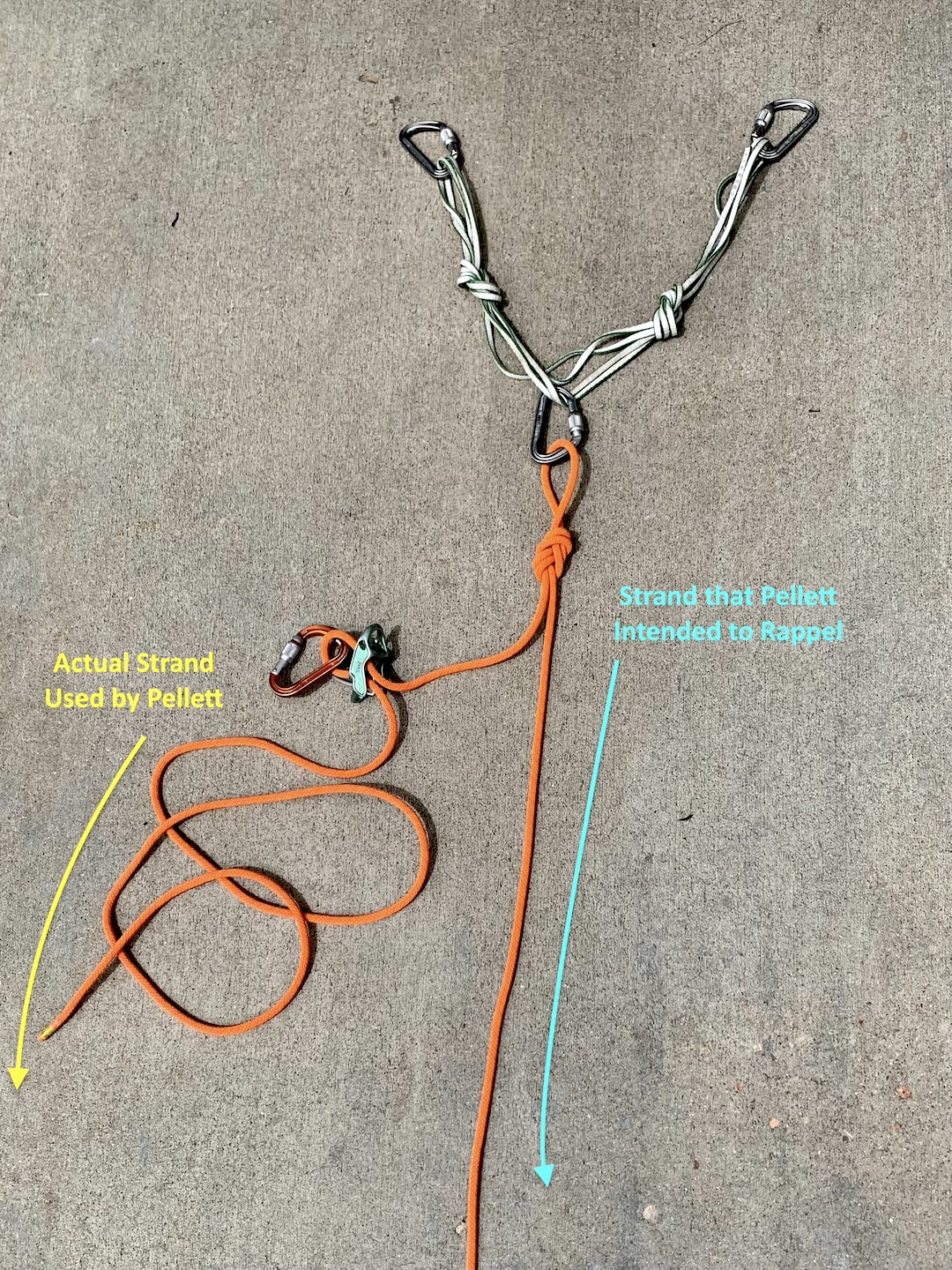

Pellett then fixed his rope to the anchor. “I took an end of the rope, tied a figure-8, and clipped it to the quad. The end that I clipped to the quad had a 15-to-20-foot-long tail, something I always try to avoid. The other end of the 60-meter 9.5mm rope lay spread out down the slab, as friction kept it from sliding fully to the ground 100 feet below.

“I put an ATC Guide on the rope and backed it up with a Klemheist knot that was clipped to my leg loop. I slipped on my rock shoes, clipped my equipment to my harness, and began rappelling. I assumed I had 150 feet of rope to work with and was not planning to rappel more than 30 feet at first (in order to assess where to place a bolt). I never double-checked anything or bothered to tie a backup knot as I was sure the rope would more than easily reach the ground.

“Unknowingly, I had clipped into the short tail of rope instead of the long strand. Two seconds after I started rappelling, I felt the end of the rope pass through my backup knot. I had just enough time to look up at my extended rappel device and watch the rope go out through it. ‘What the hell!’ I thought. I shouted, ‘NO, NO, NO!’

“I began falling down the slab. I dropped to my hands, toes, and belly in a futile effort to stop as I began sliding faster. On the way down, I caught my feet on a small, sloping dike and attempted to toss myself past it to avoid breaking a leg and /or wrecking my knees. Tumbling and sliding as the slab eased, I came to a halt five feet above the ground. Screaming from pain and fear, I butt-slid down the low-angle slab to the ground. I had bruised and bloody elbows, hands, and knees. I was wearing a helmet, and a few days later I found deep gouges in its left side. I had clearly hit my head and perhaps slid on it for a bit. I do not recall, but I’m pretty sure it saved me from a bad head injury.

“That morning, I had parked in the designated climbers’ parking lot before taking an unmarked path through the woods to the Practice Slab instead of the established climbers’ trail to the main cliff. Unfortunately, my pack with my phone and car keys was up at the anchor. Going up was impossible. I stood up and almost passed out. No one was expecting me home for several hours, and even then, they would not be worried enough to call for help right away. I was basically on my own. I waited a minute or so and stood up again. This time I was able to test my walking ability. I could hobble. I was resolved to walk or crawl out.

“As luck would have it, earlier that morning I had put in a fixed line across an insecure mossy slab that is part of the approach. It would have been impossible to cross in my condition.

“I hobbled down the overgrown trail. Maybe 20 minutes after starting, I finally made it to the dirt road. I found a bent stick to use as a crutch and continued to the nearest house. I started shouting for help. Just then, a car with two tourists drove up the road. There was no cell service in that part of the valley, but the couple was kind enough to give me a ride to a nearby town about eight miles away. Luckily, the county fair was going on and a staffed ambulance was there. Later, I had surgery to repair a torn left Achilles tendon. I also suffered a torn rotator cuff and numerous bruises and deep abrasions, which were particularly bad on my left shoulder.”

ANALYSIS

Lack of attention is at the heart of many climbing accidents. In Pellett’s case, distraction, complacency, and hurry caused him to deviate from his usual practice of properly dressing his figure-8. This misstep, along with a failure to perform his usual double-checks, led to this near-fatal accident. As Pellett recalls:

“Leaving a tail longer than three feet was something I’ve avoided in over 30 years of climbing. After several outings of installing bolts and anchors, I had become very comfortable running around on these low-angle slabs. My mother had died two weeks prior to the accident, and I was often filled with grief. Being up on a cliff was good medicine for that new hole in my heart. I guess I didn’t realize how distracted I might become.”

While Pellett couldn’t arrest his fall, he no doubt slowed his velocity, preventing more serious injury. He also showed considerable tenacity and self-reliance in performing a self-rescue. (Sources: Alden Pellett and the Editors.)