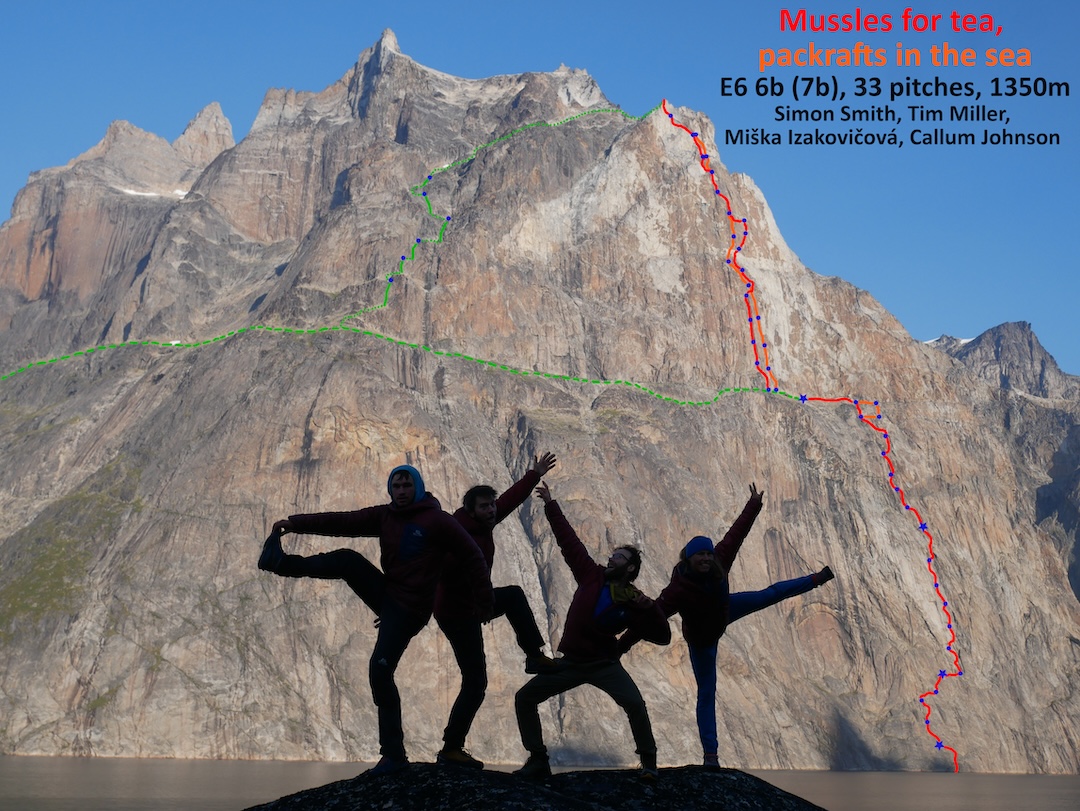

Maujit Qaqarssuasia Massif, Two New Routes, and Other Climbs

Greenland, South Greenland, Torsukattak Fjord

In August 2024, Miška Izakovičová (Slovakia), Callum Johnson, Simon Smith, and I (all from Scotland) explored the area around Torsukattak Fjord in southern Greenland. We established multiple new rock routes, including a partial new route on our primary objective, the 1,350m east face of Maujit Qaqarssuasia, a.k.a. the Thumbnail, contender for the world’s tallest seacliff. We also made the first ascent of the southern headwall of Maujit Qaqarssuasia East and established many shorter climbs on other cliffs.

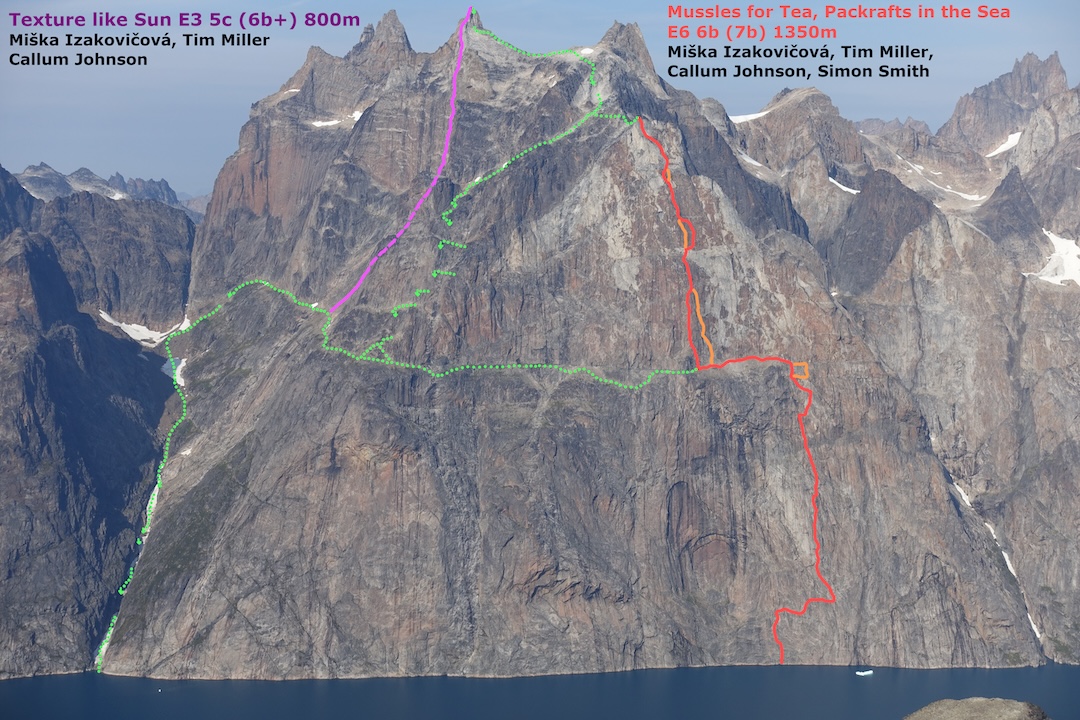

The Thumbnail was first climbed in 2000, by a 31-pitch all-free route, by a U.K. team. In the years since, four more routes or major variations were climbed, including one to the right of the original route, completed in 2016 by the French-Belgian team of Lionel Daudet, Enzo Oddo, and Siebe Vanhee. Our eyes were likewise set on the right side of this formation.

On August 1, a boat dropped us at our base camp on the west shore of Pamiagdluk Island, across Torsukattak Fjord from the Thumbnail. We were treated to wall-to-wall blue skies, and this, along with the horrendous blackflies, prompted us to head straight for the wall. We paddled both of our packrafts two kilometers across a beautifully flat turquoise sea. Miška led the first pitch onto the wall, well to the right of the 2000 and 2016 routes, and hauled the enormous bags out of our boats. Then Simon and I paddled round to the descent gully, about 1,500m to climber’s left of our line, to stash one raft, then returned to the base of our line. That evening, we set up the two portaledges and slept 40m above the sea.

We had 70 liters of water, sleeping and cooking kit for four people, and many ropes. This also meant we had exceptionally heavy haulbags. We were keen to use natural anchors, which sometimes meant using up to 12 points of gear. The next day, we climbed good rock up a series of moderate corners and soon realized the climbing was going to be the least of our worries: Ledges, long traverse pitches, chimneys, and grooves all made hauling a mammoth challenge—someone had to be with the bags constantly. We kept climbing until late in the evenings, as our horizons grew and distant pointy peaks came into view from our portaledges. After 800m of climbing and four days on the wall, we reached the halfway ledge.

We woke to gray clouds amassing on the horizon and decided to head back to base camp until the storm passed, then return to our high point. We stashed ropes, gear, portaledges, stove, and food on the ledge and then started the long traverse to the descent gully, moving slowly with our unwieldy haulbags on the steep, loose, vegetated slopes over a gaping drop straight to the sea.

Eventually we reached the snowy gully, which was much steeper than anticipated and fraught with crevasses. None of us had crampons or axes, so we each carried a spiky rock for self-arrest and abseiled over the crevasses. We finally reached the sea late in the day and under darkening skies. Miška and I set off to retrieve the stashed raft, battling choppy seas and a fierce headwind. Back at the gully, we faced a dilemma: either head out across the whitecapped fjord in the dark or sit in the miserable gully, with no food, until the storm cleared.

We took the former option, paddling ferociously in the gloom, our frayed nerves set even more ajangle when a humpback whale breached just meters away from the boats. It was a relief to be back at base camp, even if that night a storm would flood our group tent; the next day the wind ripped the big tent from our hands as we relocated it, shredding one side against some rocks, and also flattened Miška’s tent, snapping a pole.

The following day, Simon went down to the sea to fish, passing the boulder where we’d stashed the packrafts—only to find that an unexpectedly high tide and storm waves had washed the expensive rafts out to sea. It seemed we wouldn’t be able to finish our project. Worse, we looked like total idiots—though, on the upside, Simon caught a fish.

That evening, as we sat under our tarp miserably trying to turn our fish into something edible, a small boat approached our camp. It was a local fisherman. Miles down the fjord in the murky mist, he’d found one of our rafts. What a miracle: The show could go on!

After a week, the sun re-emerged. This allowed us to shuttle kit across the fjord in our single raft and then retrace our steps back up the gully and across the ledge to our previous high point. After the complexities of hauling the lower half of the wall, we had opted to attempt the top of our route in light alpine style, in a single push.

Early the next morning, we set off in two teams, climbing parallel lines. Simon and I climbed an immaculate corner up one side of a pillar, while on the other side, Callum and Miška climbed cracks and corners. We regrouped at the top of the pillar. Above, at the steepest part of the wall, Miška set off up a difficult crack in an airy position with the whole fjord far below. Callum followed with a brilliantly sustained pitch above. Meanwhile, to the right, I climbed up to a steep chimney, which Simon exited via a precarious move to reach easier climbing. These four pitches proved to be the route’s crux, ranging from British E4 to E6 (5.11b to 5.12b). We all managed to onsight and second these pitches free, bar one fall by Miška on the hardest pitch.

As we learned later, some of our headwall pitches likely shared ground with the French-Belgian route from 2016. (We found what I believe is their tat high on the face, at the time erroneously assuming it was from a failed, undocumented attempt.) But since our team climbed two different lines on much of the headwall, we undoubtedly climbed a lot of independent terrain.

The climbing above remained exposed and on quality rock right until we pulled onto the summit, late in the evening of August 15. We called our line Mussels for Tea, Packrafts in the Sea (1,350m, 33 pitches, E6 6b or 5.12b). After sharing hugs, we started down ledges behind the Thumbnail, heading generally south, until it became so steep we had to abseil. A blood-red moon emerged over the horizon; time slowed as we worked to rig abseils, pull ropes, and find the next abseil station. Soon the northern lights made a faint appearance, and a constant flow of shooting stars escorted us back along the ledge to our bivy.

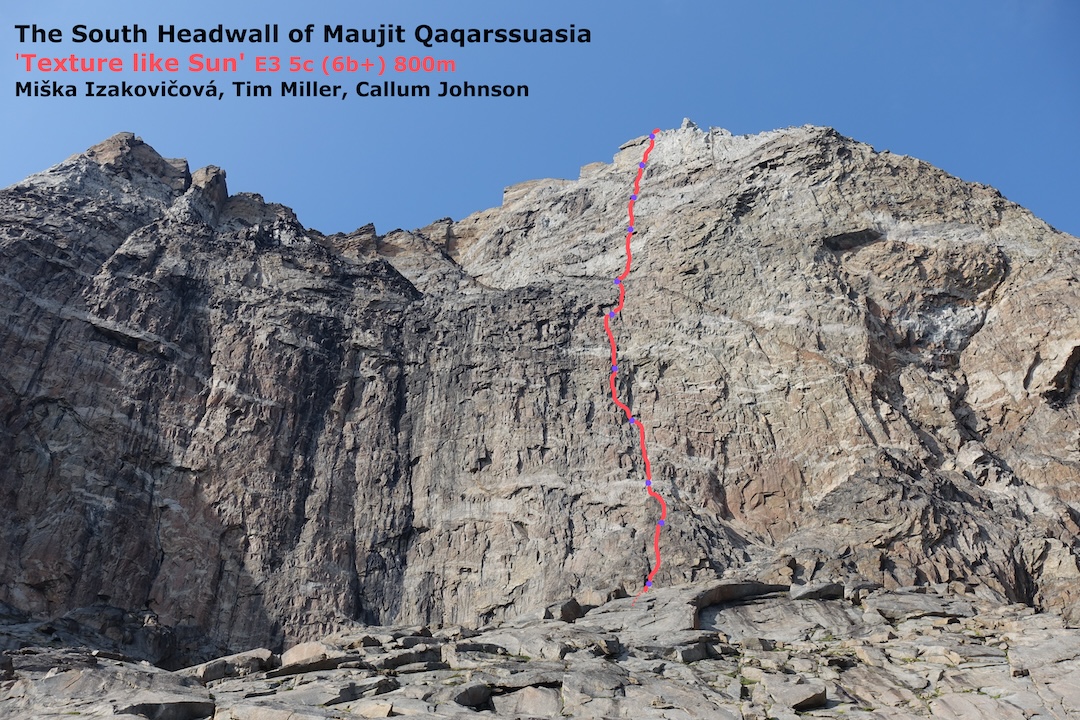

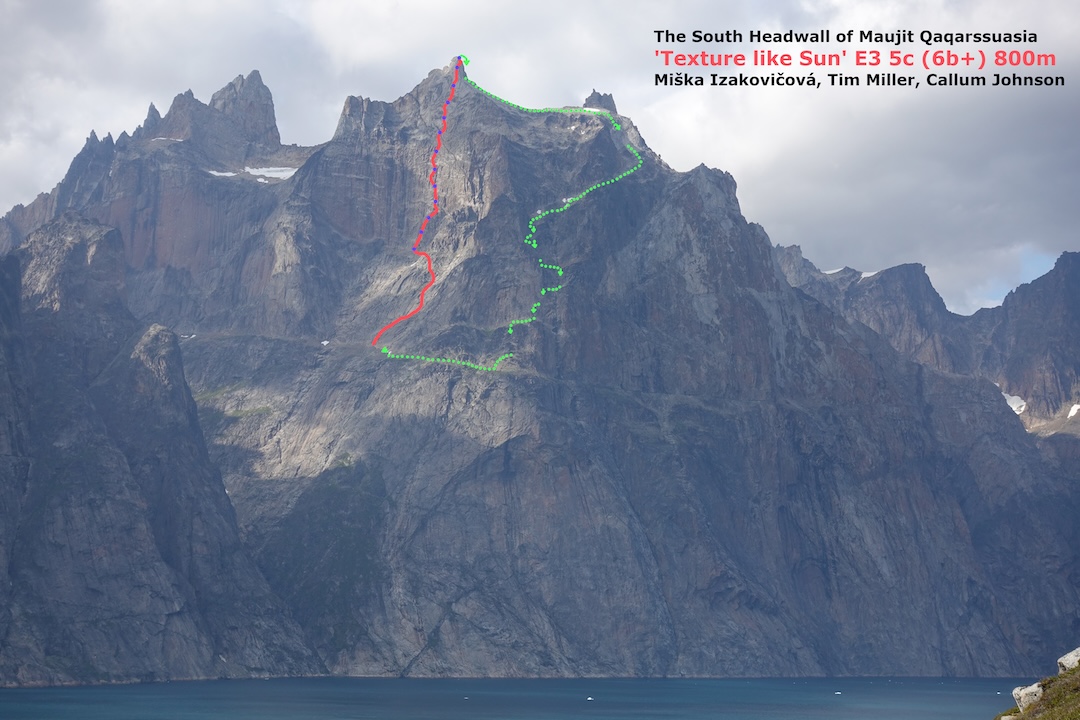

We spent a lazy morning listening to music and recovering. The forecast showed continuing top weather, and we had plenty of enthusiasm, so we relocated our camp to beneath the spectacular outhern headwall of Maujit Qaqarssuasia East, which we had set our eyes upon while walking beneath it on the ledge system. During the awkward load-carry, Simon tweaked his back, meaning he’d have to miss the climbing the next day.

On the morning of August 17, Miška, Callum, and I made quick progress up easy slabs until we stood beneath the main difficulties. We alternated leads, moving efficiently up corners and cracks we’d seen through binoculars. The climbing was constantly engaging, never desperate but sustained. We each had huge smiles after every pitch, and we could see Simon sunbathing on the ledge below.

I led a spectacular hanging corner as the sun left the wall. Then Miška climbed a final pitch up a tower, which—surprise!—led directly to the summit. Having completed the first ascent of the southern headwall of Maujit Qaqarssuasia East via Texture Like Sun (800m, E3 5c or 5.10d), we watched the sun sink behind a rugged horizon of rocky spires bathed in a deep orange glow. It was a special moment, and we would have stayed longer if not for a bitterly cold wind.

—Tim Miller, U.K.

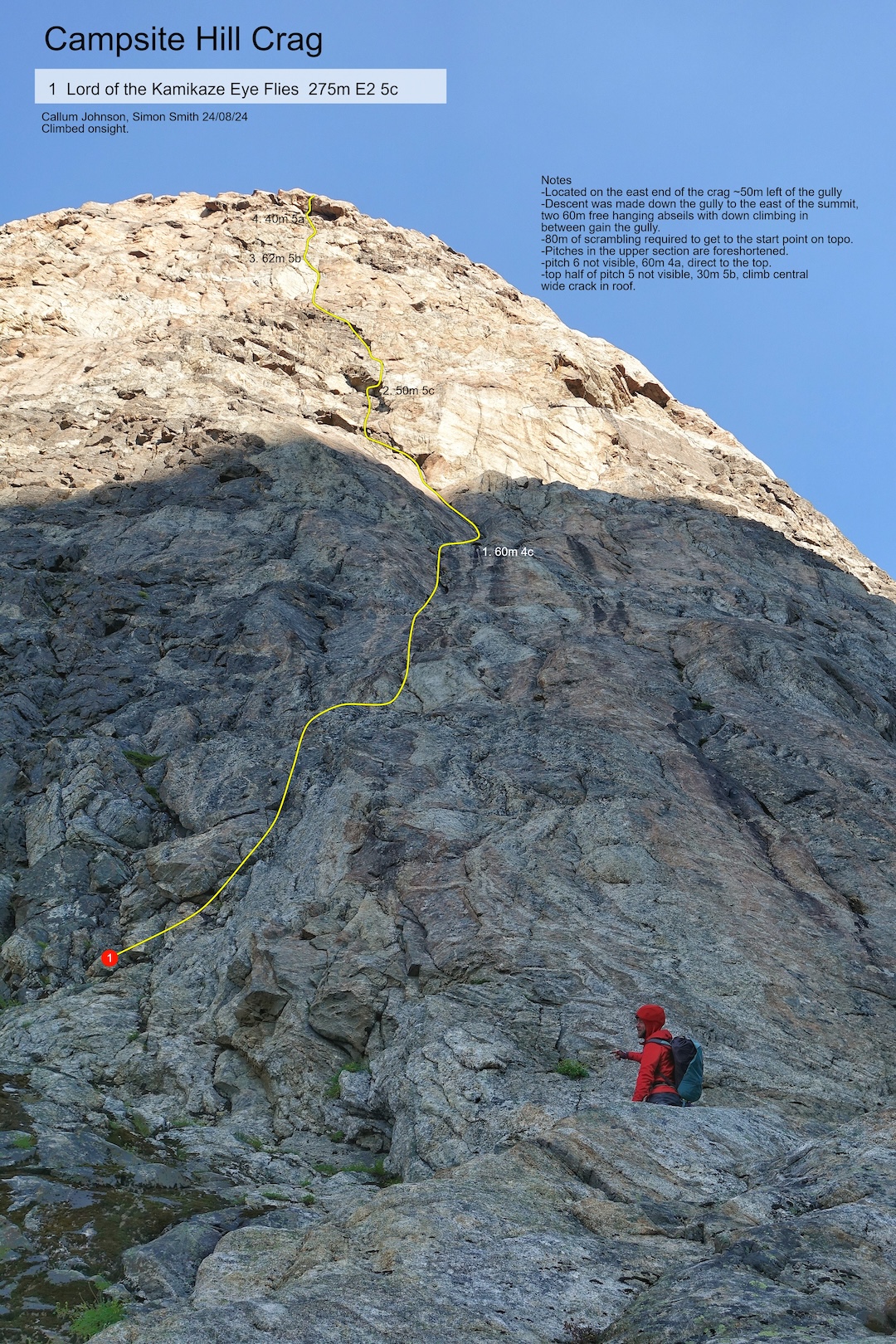

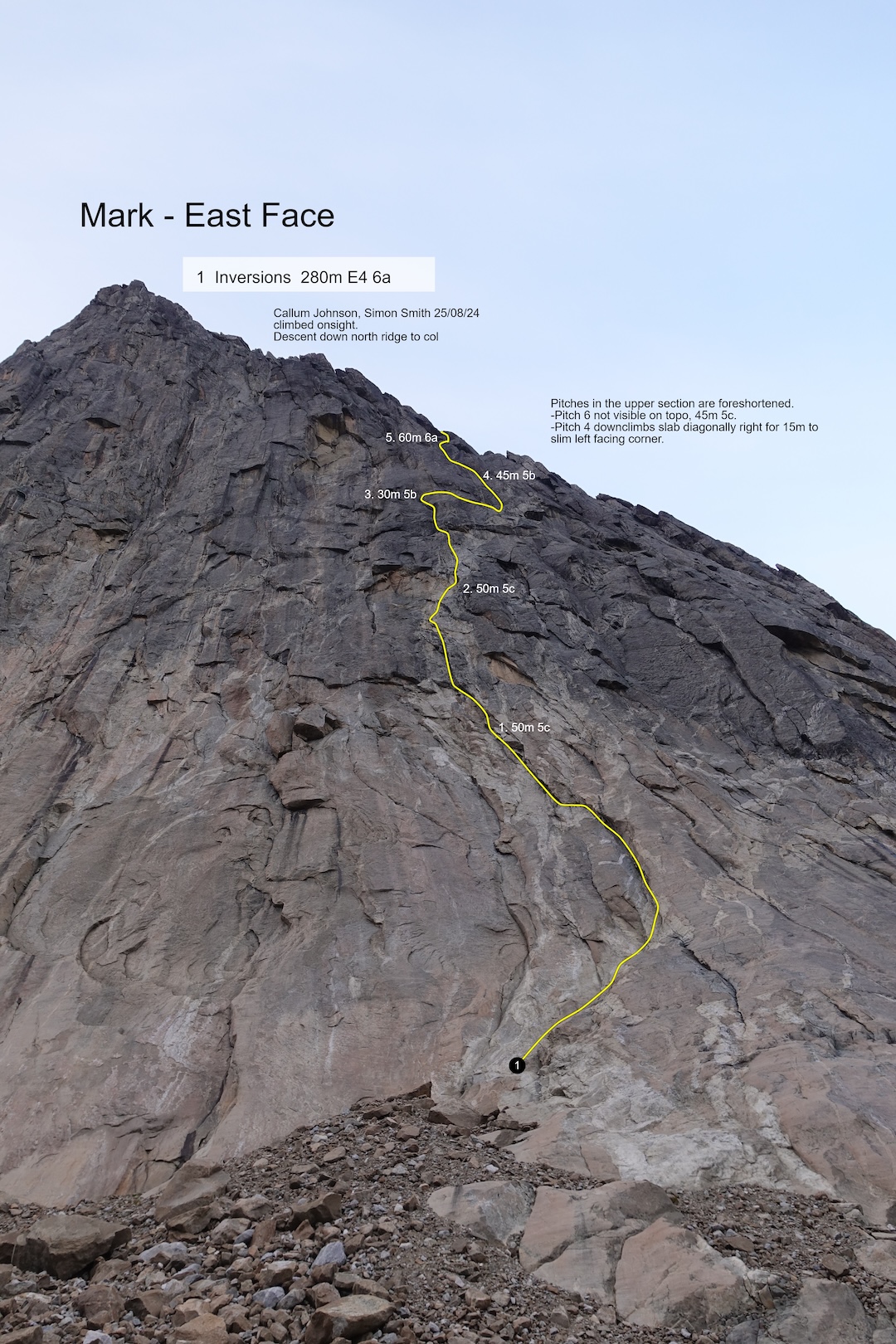

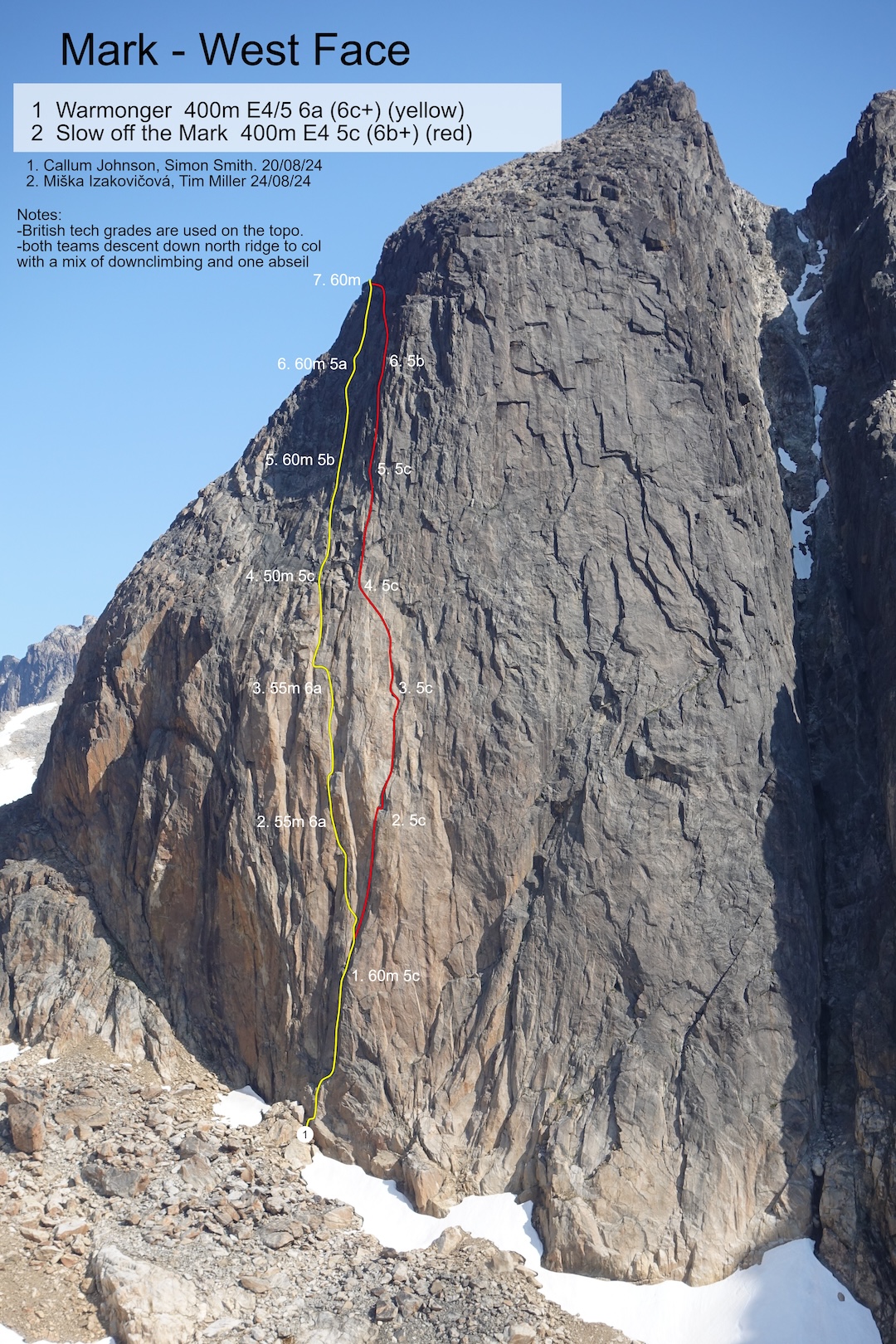

Two climbs were done on the west face of Mark, located in the same valley as the Baroness: Warmonger (Johnson-Smith, 400m, E4/5 6a or French 6c+) and Slow off the Mark (Izakovičová-Miller, 400m, E4 5c or 6b+). Warmonger may share some ground with an earlier attempt dubbed Arms Trader (300m, Mehigan-Roberts, 2002); Slow off the Mark is just left of a 2016 route and likely shares some terrain in the upper part. Johnson and Smith also climbed the east face of Mark by a six-pitch route they called Inversions (280m, E4 6a or 6c). All climbs descended to the north.

After an all-day, semi-technical approach into the mountains east of base camp, Izakovičová and Miller bivouacked for several nights and climbed three routes up the southwest face of a superb tower they called the Spire of the Northern Fire after a northern lights display above the tower. The three routes take parallel crack systems, up to five pitches long and French 7b. Descents were by rappel.

On the last day before their boat pickup, Izakovičová and Miller climbed what’s likely the first route up a formation they called Orange Wall, across the valley from Mark. Their route up the southeast face, Dream Corner (600m, E3 5c or French 6b+), involved 300m up moderate slabs followed by a steep six-pitch corner system. Descent was by a ridge to the northeast, then down a break to the southeast (two rappels), followed by a ramp to the northeast.

—Dougald MacDonald, AAJ