Sirmilik National Park, West-to-East Traverse and First Ascents

Canada, Nunavut, Baffin Island

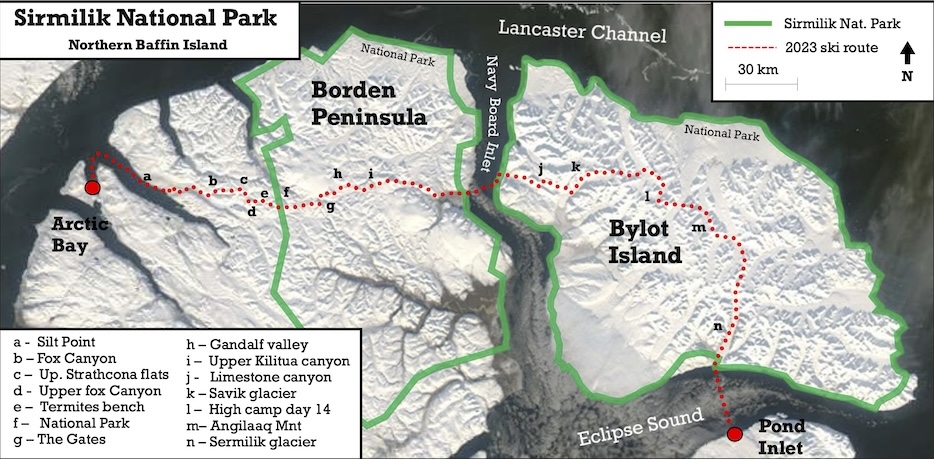

From May 3 to 29, 2023, our team of four (Philippe Gauthier and son Simon Gauthier, and Charles Gauvin and son Marc Gauvin) made the first west-to-east ski mountaineering traverse of Sirmilik National Park on northern Baffin Island. Sirmilik means "the place of glaciers" in the local Inuktitut language. The National Park was established in 1999 to preserve the unique high-arctic mountainous environment, flora, and fauna. Our goal was to explore and document a new ski route traversing Sirmilik National Park.

We skied 350km in an arctic and alpine setting consisting of valleys, glaciers, and, of course, mountains. The first portion of the route, traversed the rugged, challenging and geologically intriguing Borden Peninsula to reach the shore of Navy Board Inlet. A short crossing of the sea ice allowed us to reach Bylot Island and the Byam Martin Mountains for the second portion of the traverse. The large glacier and high plateaux of Bylot Island were unmistakably a paradise for ski mountaineering. We made several ascents on unclimbed summits, but hundreds more await the keen arctic explorer. For our traverse, we were equipped with nimble sleds and alpine touring skis. We skied in full autonomy—no cache nor resupply.

Our point of departure, Arctic Bay in Nunavut, is the northernmost permanently inhabited community in Canada after Resolute Bay, with about 800 people. After arranging a 35km drop-off by snowmobile and qamutiik (a traditional Inuit sled designed to travel on snow and ice which is built from wood and has no nails nor pins, only strings) across Victor Bay, Graveyard Point, and the Strathcona Sound, we headed on our skis near Silt Point at the mouth of the Strathcona River. Under glorious sunshine and no wind, we said goodbye to our Inuit friends (the last people we would see for the next 25 days) and started to climb a narrow, twisting drainage, feeling, for the first time, the full 120 pounds of our loaded sleds.

While the mountainous Bylot Island had been traversed by skis a few times (see AAJ 2005, for example), a key challenge for our Sirmilik traverse was to select and navigate a route across the deceptive Borden Peninsula. The northern Borden is a complex ramble of incised ravines, small glaciers, and rocky peaks—not your typical terrain for winter sled travel.

After moving up valleys of the Strathcona River drainage, we explored a series of exciting canyons—namely Upper Fox Canyon and Termites Bench—until we reached the western edge of Sirmilik National Park on day four. Once past the Gates, an intricate and obligatory passage at the base of Military Survey Mountain, the snow got more plentiful, the landscape bigger, and the overall route more gripping.

For the next two days, we stayed high, navigating perched valleys and climbing over benches, sharp cols, and minor glaciers. On day seven, the weather changed. Our primary route had us ski across the vast West Ikkarlak Glacier to exit on the shore of Navy Board Inlet—a 40km "high route" exposed to wind and crevasses. Due to the seriously deteriorating weather and whiteout conditions, we opted for an uncharted descent down the upper reaches of the Kilutea Canyon, a complex affair at first, but presumably easier to navigate thereafter.

Day seven ended up being absorbing and exhilarating and, perhaps, the crux of the route. After a few failed attempts to find suitable entry to the puzzling upper Kilutea Canyon, we managed to make good progress, descending 300m of broken glaciated slopes and ravines with our sleds to reach the main canyon below. For the next two days, under broken skies and a strong breeze, we followed the deeply incised valley of the Kilutea River east, enjoying the view of towering peaks and the 500m rock walls.

Eight days and 150km after departure, we found ourselves at sea level again, camping near the shore of Navy Board Inlet. On day nine, we crossed the 20km of solid sea ice separating us from Bylot Island, keeping a sharp eye out in this prime travel corridor for polar bears.

Once on Bylot Island, near Ikaaturiaq Point, we set camp on a bluff overlooking Navy Board Inlet. Being camped close to the shore and near a known polar bear travel corridor, this is the only night where we set up a rotating bear vigil, each enjoying a cold but magnificent three hours of "midnight" arctic sun.

On day ten, our route followed high benches above a river delta before dropping into a steep drainage to gain the main valley floor. On Day 11, we skied up the surprisingly narrow and beautiful limestone canyon to access the edge of the vast glaciated area. From here, a day of navigating complex topography of moraines, steep slopes and glacier remnants lead us to a fine position on the west side of Savik Glacier at 400m.

The 25km-long Savik Glacier became our highway to the interior. A long but gradual climb of nearly 1,000m vertical ascent offered us great views of the surrounding peaks and also a magnificent panorama of the Borden Peninsula that we had just traversed. Like most glaciers on Bylot, the Savik has vast but tamed slopes, mostly unbroken with few dangerous crevasses, a perfect carpet of untouched white snow. For the next several days, we skied in a winter wonderland while navigating high valleys and crossing a dozen passes all at the comfortable rate of 15km per day.

From a high camp on day 14, we took the opportunity of a brilliant day to make a few ski ascents and descents of unclimbed peaks, on terrain up to 45°. Skiing without the constant jerk of a sled was a welcome change, and the team was all smiles to engage in a few turns. The number of untouched, snowy peaks surrounding us was mesmerizing. [The names and coordinates of peaks climbed and skied are below.] Another break from our daily routine of “grand touring” gave us the opportunity to scale Angilaaq (1,944m) and Nukaq (1,798m) mountains.

However, we were quickly brought back down to earth. A four-day Arctic storm brought gale-force winds and deposited 30cm of snow. After a day in the tent, we decided to brave the storm and start skiing again. Navigating mainly with GPS in whiteout conditions, facing relentless strong breeze and deep snow, we reached the top of the Sermilik Glacier a couple days later. From this position at 1,500m, it was a 25km very gradual descent to reach sea level, but the storm was still raging.

By now, the snow had accumulated significantly, making travel down the Sermilik Glacier difficult. Thankfully, on the fourth day of the storm, the snow stopped falling and the sun started to break in between the clouds. We finally got our first views of Eclipse Sound and the amazing peaks bordering the Sermilik. Far in the distance, we could now guess at Pond Inlet’s location.

On the morning of the last day, after navigating crevasses at the toe of the glacier, we started skiing on the sea ice. Soon, we heard the snowmobile engine of our Inuit friends. As they got closer, we could see their great smiles beaming from their parkas. After 25 days skiing and camping out as a group of four, meeting these friendly folks was truly heartwarming.

While we were happy to end our adventure successfully, we all felt that we could have stayed longer in this amazingly beautiful arctic kingdom. The appeal of the untouched wilderness is irresistible, and nothing matches the feeling of freedom and remoteness we experienced skiing these glaciers and mountains.

—Philippe Gauthier and Charles Gauvin, Canada

FIRST ASCENTS

Peak 1,438m (Mt. Osness), 73.33627, -79.19513

E-NE ridge; ski descent by E slope, P. & S. Gauthier, M. & C. Gauvin.

5/21/2023

Peak 1,450m (Mt. Piqsiqtuq), 73.31666, -79.16897

N aspect; ski descent NW slope, P. & S. Gauthier, M. & C. Gauvin

5/21/2023

Peak 1,498m (Snow Dome), 73.33216, -79.13193

Ascent NW ridge; Ski descent NW ridge, P. & S. Gauthier

5/21/2023

Peak 1,693m, 73.24031, -78.70028

E ridge; ski descent S slope, P. & S. Gauthier, M. & C. Gauvin

5/24/2023