Tokositna Glacier Area, Begguya, Attempt on Southeast Spur, and The Water Tower, First Ascent

Alaska, Central Alaska Range

“I’m starting to wonder if this is a death mission,” Chris called down to me at the belay.

My brother Chris and I (dubbed “the Dewey brothers” in Talkeetna) were 1,000’ up the Southeast Spur of Begguya (Mt. Hunter), a route that had lurked in my mind from the moment I saw Bradford Washburn’s black and white plate a decade ago. So many things had fallen into place to put us here; I felt sure this was one of those opportunities of which you get very few of in your life. The weather over the Alaska Range had unfolded a miraculous window just as we arrived in Talkeetna on April 20. Paul Roderick agreed to drop us where no pilot had landed before, corkscrewing his Otter plane down into the cirque right below the route. Our packs were loaded with nine days of food and fuel that we figured we could stretch to 12 to get us up and over the mountain to Kahiltna Base Camp. I was surprised to be able to move upward at all after thinking my alpine climbing days were over following bilateral knee construction, but I was feeling strong. Almost everything had aligned to put us just below the crux of this lifetime dream route. The snow conditions had not.

Chris’s comment was the first time either of us had voiced aloud the fears we had both been suppressing. A few pitches earlier, as he followed me over the top of the approach couloir and onto the ridge proper, a cornice had collapsed under him, flushing down the gully we had just come up. I put the incident out of my mind, knowing there were miles of corniced ridge yet to go. As we continued up the ridge, we encountered endless facets and unsupportive snow. Much of the route would necessitate either traveling directly atop fragile cornices or passing along leeward slopes. The problem with bottling up your doubts is when you finally give them a tiny crack they come roaring out. Chris was right. I felt an enormous wash of relief as we decided to turn our back on the spur and bail back down to the cirque.

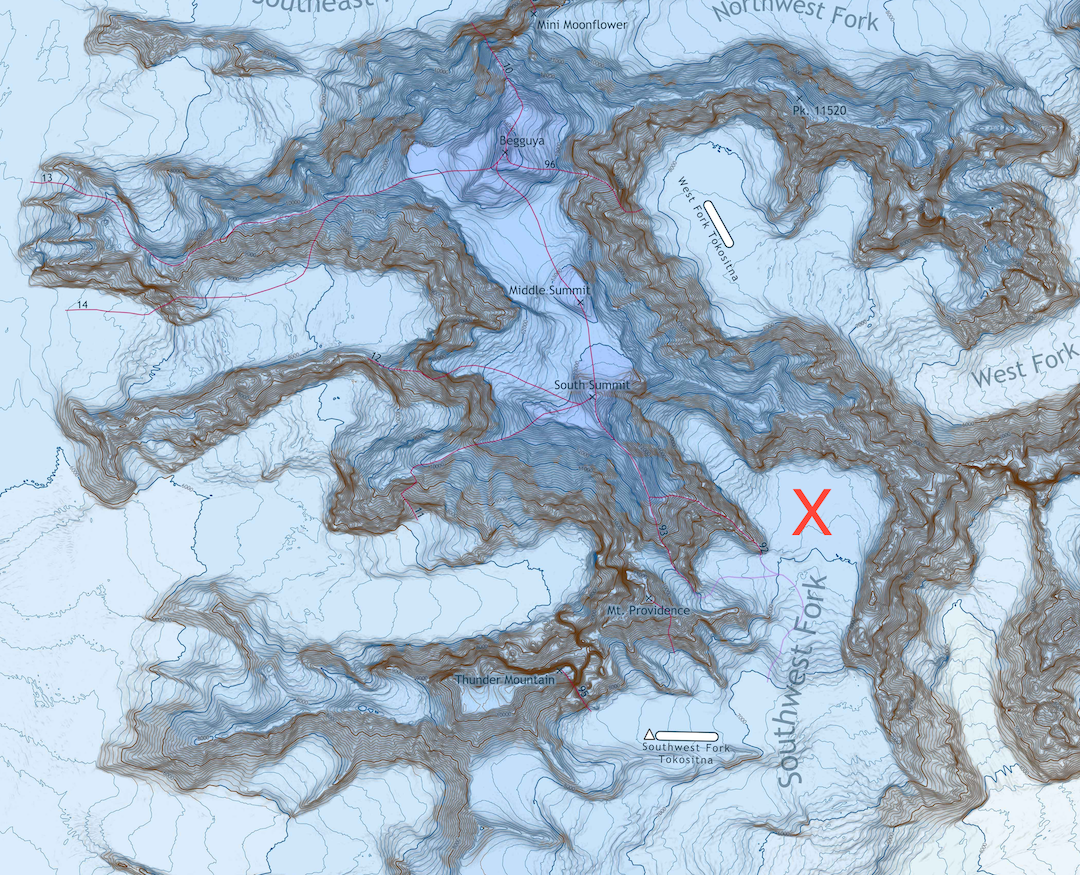

We soon found ourselves back on the glacier, a mile-wide basin northeast of the southwest fork of the Tokositna that I had begun to think of as the “Northeast Southwest Tok.” Only a few parties had been up here, and as far as I knew, they all came to climb the Southeast Spur and go over the top of Begguya. John Waterman spent 145 days establishing the route solo in 1978. Peter Metcalf made an abortive attempt in 1977 with William Nicholson, Lincoln Stoller, and David M. Sweet, before returning with Glenn Randall and Pete Athans in 1980 to make the first alpine-style ascent. In 1997, Rick Studley and Jeff Apple Benowitz battled poor snow and a chopped rope for 16 days en route to the third ascent. And in 1991, Jim Graham and Mark Kightlinger bailed down the west side of the spur after an earthquake released avalanches over the whole mountain. But I had never heard of anyone actually spending time in the Northeast Southwest Tok to climb anything else. We looked up at four rugged points along the eastern edge of the cirque. They were all probably unclimbed.

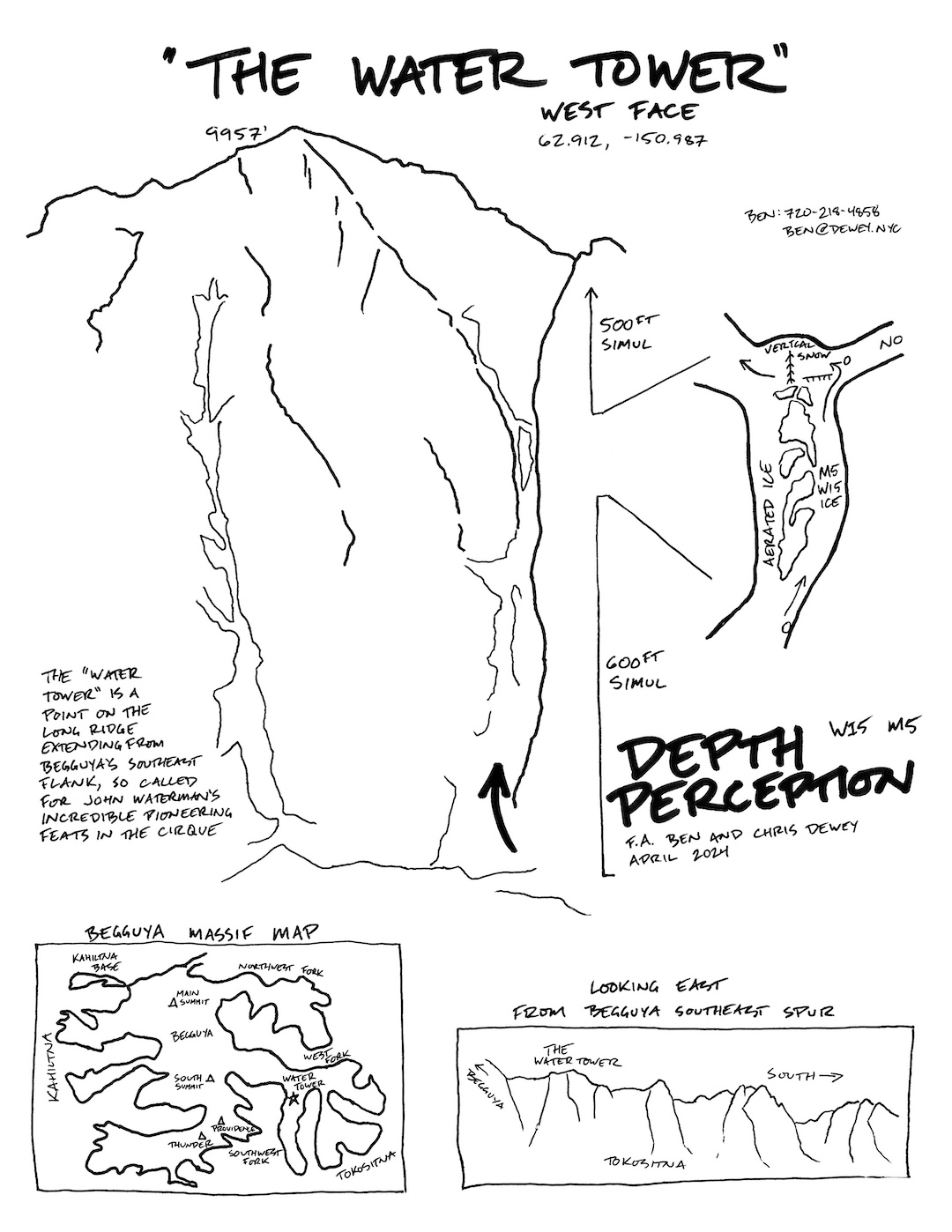

On April 24, we skinned to the base of the northernmost and highest of these points. Capped with a snow pyramid, it rises to 9,957’, according to the maps we had with us. Two steep couloirs split the west face. The right-hand one had a single constriction halfway up with what looked like promising ice; we chose that one and crossed the bergschrund.

We simuled 600’ of good snow to the base of the constriction, where the couloir forks into two side-by-side ice flows. The left (and fuller) ice leads to the summit snowfields; the right looked more mixed and went off in the wrong direction. I put Chris on belay, and he started up the ice on the left. He quickly discovered the ice was extremely aerated. It wouldn’t hold screws or even his tools. He backed down and gave the right flow a try. The first half was also aerated, so he traversed over to more mixed and protectable terrain. I hugged the wall at the belay, dodging debris as he cleared snow and ice to find even marginal gear. His pace slowed. Finally, after almost three hours, I heard a whoop as Chris reached the end of the pitch. When I joined him at the anchor, he told me that he had lost one contact lens mid-pitch. We resolved to call the route Depth Perception if we made it to the top.

We were now in the wrong gully. I led a traversing pitch left to get back to the couloir that connects to the summit snowfields. A rib of surprisingly steep snow separated the two couloirs. I chopped and chopped at the snow to try to cut a passage across, but it kept deteriorating. I tentatively reached a foot around the rib, then my knee, then just made up my mind to hop over. I was on the other side, although I had to lower down to reach the snow in the couloir. Chris followed gracefully and we were back on track.

We belayed two more pitches, then simuled again as the couloir opened into a 60° snow slope. By now, the sun was baking the mountain, and we waded upward through slushy snow. Believing the summit was a large cornice overhanging the east side of the ridge, I climbed up as high as I dared, stopping about 50’ shy of the very top. Then we downclimbed off the mountain as fast as we could, chased by visions of wet slides.

Back at camp, sorting the remains of our pitiful rack, we decided to call the mountain the Water Tower in honor of John Waterman’s incredible pioneering feat in the cirque. I am quite proud to have put in an honest attempt at the Southeast Spur and to have found our own little first ascent in the area. Depth Perception (1,300’, IV WI5 M5) was only one of what appears to be a fair number of exciting objectives in the Northeast Southwest Tokositna.

Thanks to Paul for landing us in the cirque based on an X I drew on the map, and to Talkeetna Air Taxi for giving us a $1,000 grant toward flights, which allowed us to resupply in Talkeetna, fly back to the Tok below Thunder Mountain, climb the forgotten gem Deadbeat (Cordes-DeCapio, 2001), get stuck in a storm, miss our flights home, run out of food, and starve for a few days before our Alaska season came to an end. But that’s another story.

—Ben Dewey

Editor's Note: A date in the brief history of attempts on the southeast spur of Begguya was incorrect in the print edition of AAJ 2025. It has been corrected here.