Keeler Needle, East Face, Keelhaul

California, Sierra Nevada, Eastern Sierra

For five packed seasons, from 2018 to 2022, my main mate, Chase Leary, and I established hard multipitch first ascents on some of the best climbing formations in the High Sierra. In the northern Sierra, we looted the Incredible Hulk, establishing Green Thunder (700’, 5 pitches, 5.13b) and Up in Smoke (700’, 6 pitches, 5.13a). In the central Sierra, Trapezoid Peak provided a bounty of four great routes, including Shield of Dreams (700’, 5 pitches, 5.13b), with the High Sierra’s only gear-protected 5.13 pitches (AAJ 2023). We were hungry for more, so we turned to the great Whitney Massif in the southern part of the range for more “Calpinism”—the stellar weather and epic granite form of alpinism in California’s High Sierra.

At 14,260’, Keeler Needle is the proudest spire on the Whitney Massif. Nearly perfectly symmetrical and rising 2,000’ from the glacier to the Sierra Crest, Keeler is flanked to the north by Mt. Whitney and to the south by Day Needle, both also over 14,000’. Unlike its blocky neighbors and most Sierra mountains, Keeler is a sheer face capped by an overhanging headwall, a tower that would seem more at home in wild Patagonia or Pakistan than in mellow California. Legends such as Warren Harding, Jeff Lowe, and Ammon McNeely have grabbed first ascents up this high-country prize.

In late 2022, I began to study photos and topos of Keeler’s east face. I knew about the Harding Route, established in 1960 and freed in 1976 by Galen Rowell, Chris Vandiver, and Gordon Wiltsie, and still considered one of the mega routes of the range. I wanted to learn about the more modern routes.

In the center of the east face is The Crimson Wall (2,000’, 16 pitches, 5.12 A3), put up well before its time, in 1991, by Kevin Brown, Mike Carville, and Kevin Steele (with a 5.12 direct finish added by Brown and Carville the following summer). I remember getting an issue of Climbing magazine and reading a short but eye-popping paragraph about their ascent. Sport climbing had barely been invented, and there were only a handful of 5.13 climbs in all of California. This was 5.12 at 14,000’ in the High Sierra. The Crimson Wall stands as one of the most visionary lines in the entire range.

Most recently, in 2012, the local hardcore duo of Myles Moser and Amy Ness established Blood of the Monkey, a proud and burly free line (2,000’, 16 pitches, 5.12a). This hard-fought route has seen only a handful of repeats, with reports attesting to its bold style and engaging climbing.

To me, the most promising route for a new free climb on the Needle came from the legendary aid master Ammon McNeely, a.k.a. the El Cap Pirate. In 1999, Ammon and Kevin Conti spent eight days nailing and hooking up the dead center of the wall, establishing the brilliant line Australopithecus (2,000’, 16 pitches, 5.10 A3+). The route takes a thin crack up the middle of the 300’ headwall, and Ammon named it “the Gemstone.” I was smitten.

Winter of 2023 arrived, and it was off the charts. The largest-ever recorded snowfall in the Sierra piled up over 700 inches on the East Side. For months I studied Ammon’s route in every internet photo and topo I could get my hands on. Almost every morning, coffee mug in hand, I would check out Australopithecus, feeling a strange sense of connection.

February brought a one-week break in the weather. I called Chase, a ski patroller at Mammoth Mountain, and asked if he’d be game to ski up from the desert to scope the route. We planned to go on the following Monday, but on Sunday something terrible happened: Ammon died. He had driven with his partner, Sarah Watson, to watch the sunset from a cliff near his home in Moab, Utah. Walking out onto a rocky point, Ammon lost his balance and fell. Although I had met him only once, and knew him mostly through Valley lore and films, I perceived a powerful omen.

Finally, spring arrived, and in April 2023 we got to work. Our strategy was to climb the Harding Route and then traverse the face and rappel our line to see if it would go. This mission proved exciting, with snow, ice, and sketchy anchors. Our morale was boosted when we discovered that the first eight pitches would make for great free climbing up to about 5.12+.

The next mission was to check out the daunting headwall. We slogged up Whitney’s Mountaineer’s Route and summited Keeler from the back side. We rapped 400’ off the top, to Harding Ledge, then lowered into the unknown.

The headwall was mostly a blank panel—steep and airy. The Gemstone crack split the center, much like the Salathé headwall crack, undulating between fingers and hands, with an occasional pod offering a rest. Although a few sections were discontinuous, there were intermittent face holds. We knew we were in for it.

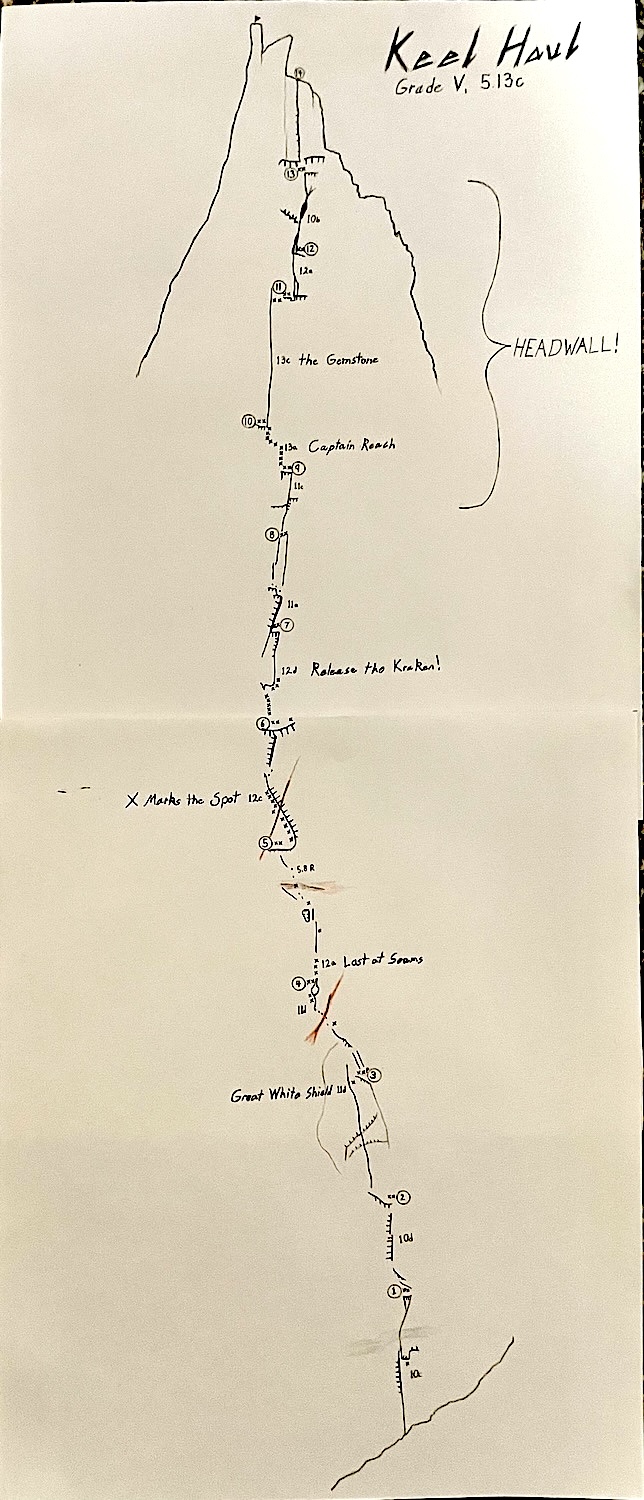

For 18 weeks straight, we made long day trips from Bishop up to the Whitney cirque to clean and buff the line, for beauty and safety. Arriving at the wall after the five-mile, 4,600’ approach, we would jumar or Mini Traxion fixed lines to work on different pitches. In the spirit of Captain Ammon, we adopted pirate attitudes and humor, filling our days with seafaring jokes. Ammon’s topo included pitches called “The Great White Shield” and “X Marks the Spot,” as well as the Gemstone. Half the pitches we established were variations to the aid line, and we added our own monikers: “Release the Kraken” is an ultra-pumpy, overhanging 5.12d flake that tends to drool a slimy black streak after a good rain; “Captain Reach” is a 13a bolted pitch with a painful pinky-lock move that tested even this six-foot-sixer’s reach; “Lost at Seams,” 5.12a, navigates a tiny off-vertical fissure through a series of intricate laybacks.

As we dialed the other pitches, it became clear the route came down to the Gemstone. At around 5.13c, the pitch was at both of our redpoint limits, and we understood why hard rock climbing at altitude was so much more intense. Climbing 1,500’ to rehearse the pitch kicked our asses every time. We adopted new breathing techniques to deal with the thinner air, going into a trance of loud, powerful exhalations for minutes at a time to hyper-oxygenate. Often the belayer would count out the minutes aloud as the climber gasped for air at rests, making sure he stayed long enough to calm his heart.

The line of Keelhaul (2,000’, 17 pitches, 5.13c). Photo by Andy Puhvel

In late September, we finally took a burn at the one-day send. Reaching the Gemstone without falls, we were both too exhausted even to have a go. The following week we tried again, this time sleeping poorly halfway up the wall in a portaledge. Chase gave it his all on the Gemstone, screaming his way up the final 20’ of first-knuckle locks, only to take a spectacular 45-footer onto a tiny purple Metolius TCU. After 21 trips and two failed send burns, our season ended.

In April of 2024 we returned, having trained like fiends all winter. We reacquainted ourselves with the route, and within four quick trips felt ready. On our first redpoint attempt, we arrived at the headwall with fatigue and nerves getting the best of us. We had one more week and one more try before other plans would divert us. As we drove up to Whitney Portal on our 26th mission, deep burnout began to show.

“I’m kinda over it,” Chase let slip. I agreed. Both of us knew we couldn’t sustain our psych for these trips all season, and if we weren’t fit enough now, we doubted we ever would be.

That evening we camped in the talus and strategized. Years of free climbing walls manifested in a barrage of ideas on how to save energy: Don’t pull the cam triggers too hard, just gently; never rack the gear on your harness when following, just let it hang on the rope so the belayer pulls it up; relax your hands in every jam; and don’t overgrip.

On June 5, we set sail up the first ten pitches, with me taking the bulk of the leads as a warm breeze blew up from the hot Owens Valley. We arrived at the hanging belay below the Gemstone, pitch 11, as the sun shifted to the west and shade chilled us. Chase bundled up in two down jackets and hunkered down for 45 minutes of rest. I insisted on massaging his forearms to get rid of any lactic acid. We pulled out all the tricks.

This time Chase floated, like nothing mattered, arriving at the belay to screams and tears of sheer mutual elation. I followed the pitch free—we each freed everything on the route, either on lead or seconding—unaware of dark thunderclouds creeping in overhead. As I stuck the final jug, the sky let out a deafening smack of thunder. The timing couldn’t have been any crazier; the universe seemed to know we had broken through, and our energy synchronized with that of the mountains. As it began to drizzle, we hustled up the final 5.12a finger crack and onto Harding Ledge, thanking Keeler for her treasure and Captain Ammon for his map.

What about the summit? The next four pitches were only 5.10, but, if it kept raining, they would be unclimbable. Chase always tells me, “If you don’t like the weather in the High Sierra, wait half an hour.” Sure enough, the skies cleared to California blue, and we climbed to the perfect tabletop summit of Keeler Needle, where we belonged.

Editor's Note: The climbers named the route Keelhaul (17 pitches, 5.13c). About half of the route follows the original line of Australopithecus; half of the pitches are new. Twenty-six protection bolts were placed, including some on previously aided pitches to enable safe free climbing.