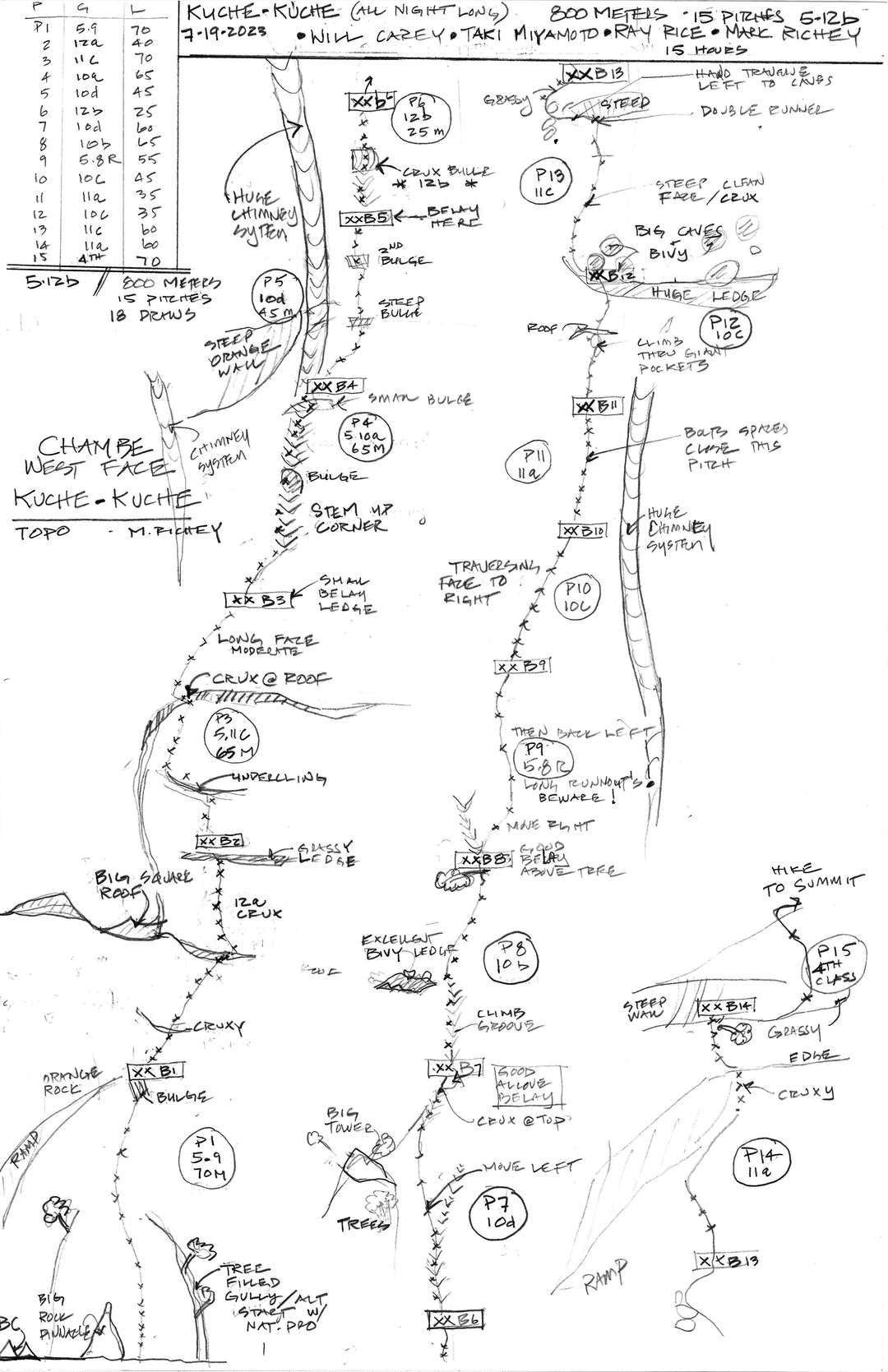

Chambe, Northwest Face, Kuche Kuche

Malawi, Mulanje Massif

Across the African plateau, rising smoke from slash-and-burn agriculture gave an orange haze to the setting Malawian sun. One by one, electric lights illuminated the towns far below us, and the rhythmic drumbeat of pop music from small bars gathered in volume. A troop of blue monkeys, rare in these parts, traversed the wall above our camp, foraging and chattering. A four-inch-long African millipede slithered along the cliff, then disappeared under our tent.

“That’s why I’m up here,” piped Will Carey, cocooned in a hammock he had suspended between boulders. He and Ray Rice—two of my three partners on this trip, along with Taki Miyamoto—had been very concerned about snakes and other critters when I convinced them to come halfway across the world to Malawi.

We’d been at the Mulanje Massif, in southern Malawi, for two weeks, equipping a new route on the dramatic, 800m upper northwest face of Chambe. One of 62 named peaks in the massif, Chambe and its two-tiered face is a sight to behold, and we were a hair’s breadth from finishing the first modern route on the upper wall. But we only had two days left before we’d fly out— and, of course, for the first time on our visit, it had just rained. Mist clung to the wall, delaying—and possibly foiling altogether— our final chance to free the route.

On my first trip to Mulanje, in 2022, James Garrett, Mark Jenkins, Geoff Tabin, and I focused on repeating routes. After climbing James’ 2018 line Passion and Pain (630m, 11 pitches, IV 5.9), a slab climb on Chambe’s lower wall, we added (but didn’t free) a 60m 12th pitch to the terrace at 5.11 A0. From there, we gaped at the bigger and much steeper wall looming above. Except for one chimney system, the West Face Direct (VI 5.10 A1), climbed by Frank Eastwood and Ian Howell in 1977, the huge wall was untouched.

With that brief up-close glimpse of Chambe’s upper face, I hatched a plan to return and establish a direct new route. The upper wall has the same highly featured, solid rock as the lower face and similarly few cracks. I imagined it would require a serious ground-up bolting effort, so I invited a crack team of close friends—Will and Ray, both from New Hampshire, and Taki from Maine—all with deep experience in exploratory rock climbing and bolting.

On June 19, we arrived in Blantyre, Malawi. We spent the first morning gathering supplies before our friend, hotelier, and local fixer, Ruth Kalonda (“Auntie Ru”), picked us up in her van for the two-hour trip to Mulanje and the Hiker’s Nest, the cozy guesthouse that would be our base. The following day, we repeated Passion and Pain to regain the terrace and inspect the upper wall. Pulling onto the roughly 3km by 0.5km terrace, where a tangle of ancient trees and massive boulders guards the upper cliff, we were met by local hiking guides George Pakha and Witness Stima, whom we had hired to help us out. They had reached the terrace by hiking up steep slabs at the north end of the lower face.

On June 19, we arrived in Blantyre, Malawi. We spent the first morning gathering supplies before our friend, hotelier, and local fixer, Ruth Kalonda (“Auntie Ru”), picked us up in her van for the two-hour trip to Mulanje and the Hiker’s Nest, the cozy guesthouse that would be our base. The following day, we repeated Passion and Pain to regain the terrace and inspect the upper wall. Pulling onto the roughly 3km by 0.5km terrace, where a tangle of ancient trees and massive boulders guards the upper cliff, we were met by local hiking guides George Pakha and Witness Stima, whom we had hired to help us out. They had reached the terrace by hiking up steep slabs at the north end of the lower face.

After a few hours and some drone inspection, we settled on a direct line up the tallest section of the face, about 500m left of the start of the Eastwood-

Howell route. A small, flat area at the base would make a perfect camp for three-to four-day missions away from the Hiker’s Nest to clean, bolt, and work the route.

Following Witness and George, we descended to the valley along 2,000 vertical feet of polished slabs and steep trails. Local woodcutters—many just young boys and girls—use these daily to access the terrace. It was humbling to see these tough people at work, gracefully descending fourth- and even fifth-class slabs with incredibly heavy loads, barefoot, often laughing and singing. Along the trails were little streams and myriad red, blue, and orange flowers, from begonias to balsams. Tiny malachite and double- collared sunbirds flitted hummingbird-like between the flowers, flashing their brilliant gorgets. Back at the trailhead, Auntie Ru was waiting to shuttle us back to the Hiker’s Nest for hot showers, home-cooked food, and plenty of Kuche Kuche—the local light beer, which translates to “all night long” in Chichewa.

Though we had already obtained a permit from the Mulanje Mountain Forest Reserve and had been in touch with Ed Nhlane, a board member of Climb Malawi, to ask advice and share our plans, we also set up a meeting with the local village chief as a sign of respect and to ask his permission to climb on the upper wall. Chief M’Pwanye, his wife, and several elders welcomed us warmly, expressed interest in our adventure, and said they would alert the woodcutters so they would not be alarmed by our activities.

Over the next few days, George and Witness began ferrying supplies up to the terrace as we set up camp and started the methodical job of establishing our climb. We quickly realized we could leave behind all of our trad gear—there simply wasn’t any opportunity to use it. We also found that the climbing was going to be fantastic. The rock was steep but not overhanging, and there was far less gardening than anticipated. Although the rock is syenite, similar to granite, it climbs more like limestone, with delicate crimps, tufa-like rails, and huge solution pockets. The climbing only got better as we pushed higher.

We worked in teams of two: one pair would lead, drilling from stances or hooks; the other team would follow up fixed ropes, cleaning, working the hard sections, and adding bolts as necessary. Rope-stretching pitches of 70m led to perfect belay ledges, including a killer bivy site on pitch eight. It was cool in the morning and at night, but warm enough to climb with just a long-sleeve shirt during the day.

After four missions on the wall, with rests in between at the Hiker’s Nest, we had reached the summit slabs. On the afternoon of July 3, we all scrambled to the top of Chambe. The view was magnificent: The steep mountains and cliffs of Mulanje gave way to ancient erosional plains stretching as far as we could see. After making 15 rappels and removing all of our fixed ropes and gear, we were back at our tents—tired, dirty, but ecstatic. All that remained was a bit of rest and a one-day free ascent.

Back at the Hiker’s Next, as we prepped our gear for a final free attempt, the lights flickered twice. The 230-volt Malawian outlets had fried the 110-volt-compatible chargers for our drill batteries. Thankfully, Auntie Ru knew just the repair shop for the job, and four hours later our chargers were fixed and all 12 batteries juiced up. (Note to self and any future visitors: Bring a step-down voltage transformer.)

Then something else unusual happened—it started raining. The wet approach slabs were too dangerous to ascend; we had to wait for the weather to clear. Finally, with only a day to spare before flying out, we made it back to our terrace camp. That night, as the sun set and we listened to the now familiar bar music, it rained again.

Fortunately, July 19 dawned clear with a chilly wind. We struggled to heat coffee over a tiny fire of sticks, since our petrol stove had died. I worried whether we could keep our fingers warm for the sustained crimping of the 5.12a second pitch. But as we got moving, our bodies warmed and the familiar pitches flowed by. As Taki sent the powerful 5.12b crux on the sixth pitch, I could hear Will and Ray whooping and hollering as they cruised the sunbaked pitches above.

By midday, we’d climbed eight of the route’s 15 pitches. But halfway up pitch nine, I couldn’t find our bolts! It was the route’s easiest pitch (5.8), so we hadn’t added any bolts after the initial lead. For a few scary moments, I traversed aimlessly around, 12m out from the last runner. At last, the anchor came into view. (Subsequent parties should feel free to add a few more bolts to this pitch.)

By midday, we’d climbed eight of the route’s 15 pitches. But halfway up pitch nine, I couldn’t find our bolts! It was the route’s easiest pitch (5.8), so we hadn’t added any bolts after the initial lead. For a few scary moments, I traversed aimlessly around, 12m out from the last runner. At last, the anchor came into view. (Subsequent parties should feel free to add a few more bolts to this pitch.)

Come late afternoon, we had passed the Caves, a series of massive solution holes big enough for all of us to lie down—this section held some of the best climbing of the route. My fingers were sore and my hands had started to cramp, but two pitches later we all stood on top. At least one person had led every pitch free, and all four of us had freed each pitch either while leading or seconding. Later that night, after a four-hour headlamp descent, we settled into our tents and hammocks on the terrace and cracked a round of delicious Kuche Kuches. The appropriate name for our new route seemed obvious.

In establishing our new route Kuche Kuche (800m, 15 pitches, 5.12b), our goal was not just to get up the wall but also to create a fun climb that other people, including the growing local climbing community, could repeat and enjoy safely. And, for the record, there is no concern of venomous snakes in Mulanje.

—Mark Richey, USA