Pik Trud, West Face

Kazakhstan, Tien Shan, Zayliyskiy Alatau

Starting in the 1930s, a large Soviet climbing camp operated in the Middle Talgar Gorge. In summer it hosted hundreds of alpinists from all over the USSR. A 1979 mudflow devastated the camp, with most of the buildings destroyed or buried under massive boulders. Since then, the number of visiting climbers has greatly reduced, and in the early 1990s Talgar became part of the Almaty Nature Reserve and no one was allowed to enter the gorge. Later, it was reopened, but the lack of good trails, the considerable bureaucracy involved in acquiring a permit, and a little bit of corruption all combined to keep most climbers away.

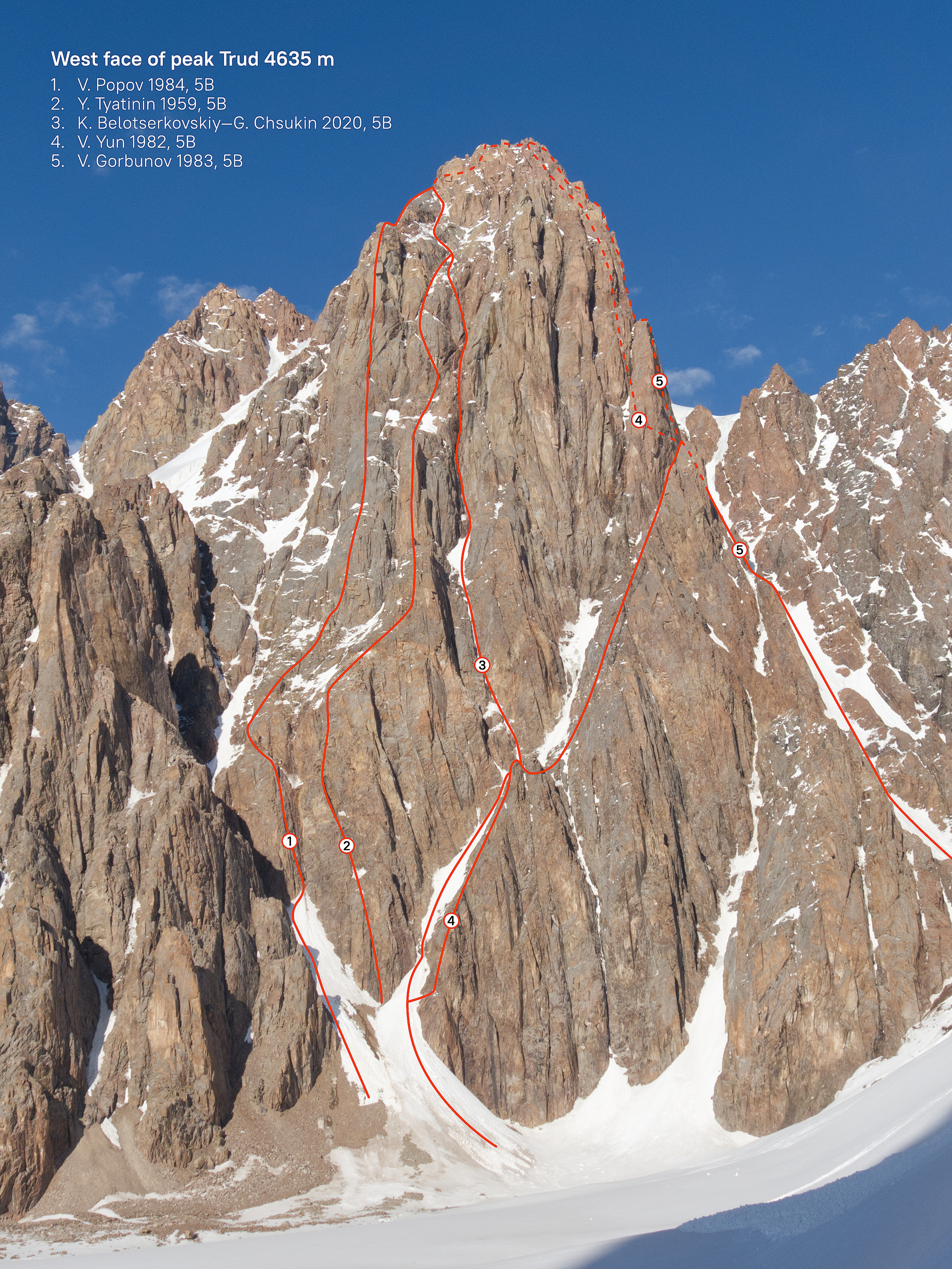

Though hard to reach, the highest summit in the area, Pik Talgar (4,973m), and nearby Pik Trud (4,636m) are less than 35km as the crow flies from Almaty, the largest city in the country. Routes on the west face of Trud were mostly put up from the late 1950s to 1980s. The rock is a type of granite, mostly solid. The only attempt to climb a new route on the west face in recent years took place in 2015, when Tursunali Aubakirov and I tried a line to the right of the Tyatinin Route (1959). We ran out of steam and bailed less than half a pitch from easy ground.

I decided to finish the route in May with Grigoriy (Grisha) Chshukin. The approach took two days, crossing two passes and traversing about 30km of forest, glacier, and moraine. At noon on our second day, we camped on the moraine of the Kroshka Glacier. We decided to take a rest day, and that evening I scrambled up to a col from which I could see our prospective descent route. It looked like a gentle snow ridge. Hah!

We started at 2:30 a.m. on May 28. In 30 minutes we had reached the base of the snow couloir leading up to our chimney system on the face. Above the snow, we climbed two steep but straightforward ice/mixed pitches to reach a section of rotten ice covering a vertical wall. Five years earlier, this had been a pure water ice pitch. Now I had to torque my tools into a shallow crack and gently tap into the thin ice above.

A couple of pitches higher, I found myself stemming, pushing, and puffing in a gently leftward-leaning chimney. There was climbable ice inside, but the walls held a thin layer of verglas, beautiful as candy. It was hard but fun climbing until I reached a sort of ice chockstone, where it simply became hard—but, hey, it doesn’t have to be fun to be fun! I scraped holes with my picks, as hitting the chockstone feature was just too scary, and slowly scratched up to a belay.

Above this, a loose, overhanging chimney led to the 2015 high point. Back then, I'd had a frightening time trying to aid past loose blocks, trying two different lines before thankfully dropping part of my aid kit and having to bail. This time I was wiser and had brought rock shoes.

The corner had a blank vertical wall on one side and an infestation of loose blocks on the other. I had to place my feet on the tiny features of the vertical wall and press those loose things with my palms. The climbing was 6b, but a totally different pitch from a 6b at the crag. Fortunately, it was the last hard pitch. Seven easier pitches got us to the summit, during which time a stone hit me on the eyebrow. There was blood over my face and my sunglasses were broken. Never mind—keep climbing!

We arrived on top at 7:30 p.m., spent only a few minutes, and then rushed off down the northeast ridge. First we downclimbed to a notch between gendarmes, then made seven rappels to the northwest from Abalakov anchors to reach the ridge I had seen from the col. It was already dark. There was no moon, and the pale stars gave us no light. The snow on this ridge, which connects Pik Trud and Pik Extra, became wet and unsupportive, the crust collapsing under one’s weight. This went on for two dreary hours until we reached a notch where a couloir leads southwest down to the glacier. During my inspection two days earlier, the mid-size scree slope had looked better than it now felt, but it wasn’t as rough as trail breaking through deep, wet, crusted snow.

We reached the tent 23 hours after leaving. I drank a little water and crawled into my sleeping bag. Grisha—younger, stronger, and hungrier than me—was already rattling pans and cooking something to eat. We felt the 1,200m route to be Russian 5B, M6 WI5 6b.

– Kirill Belotserkovskiy, Kazakhstan