Jim Bridwell, 1944 – 2018

THE WORLD has lost a great climber, friend, and mentor.

Jim Bridwell made huge contributions to the world of climbing. He was adept in free climbing, big wall, and alpine climbing, establishing over 100 first ascents in Yosemite Valley and multiple alpine routes in places like Alaska and Patagonia. He, along with John Long and Billy Westbay, was the first to climb the Nose of El Cap in a day. He helped to create the famed YOSAR rescue team, with a core of skilled climbers. In 1979, Jim and Steven Brewer did the first alpine-style ascent of the infamous southeast ridge of Cerro Torre (and first ascent to the true summit by this route). Two years later, he teamed up with Mugs Stump and climbed Dance of the Woo Li Masters, the first route up the massive east face of the Mooses Tooth in Alaska. Jim was a visionary, always pushing the limits of the sport and upping the ante.

I was able to visit “The Bird” a few weeks prior to his passing at the Loma Linda hospital, an hour from his home in Palm Springs. As I was pulling up to the parking garage, Jim’s wife, Peggy, called and told me that Jim had just gotten the news that he was no longer a viable candidate for a kidney transplant. Cancer riddled his kidney.

Silently I pondered. Silently I protested. I walked in to visit with my friend of 43 years, apprehensive of the antiseptic smell in the otherwise pleasant hospital. I glanced at posters of encouragement that lined the hallways and contemplated how I could possibly greet him after such atrocious news. I reflected back on the time I first met this giant of the climbing world.

As a teenage climber who was obsessed with the sport and its host of mythical characters, Jim was to me and to the climbing world what Michael Jordan was to basketball. I had just tied in and racked up to lead the first pitch of New Dimensions in Yosemite Valley, my first 5.10 crack climb, when Jim appeared out of the bushes and struck up a friendly conversation. I would have been star-struck had the task at hand not been so forbidding. With my eye on the prize, I hastened my departure.

Lacking the fitness to hang out and place lots of gear, I opted to go fast and not fuss with unnecessary protection in the relatively secure hand crack. At the transition to the second crack, just short of the belay, I made the rookie mistake of stepping on my rope and then careened 40 feet through space. Discouraged and humiliated, I pulled back into the crack and finished the lead.

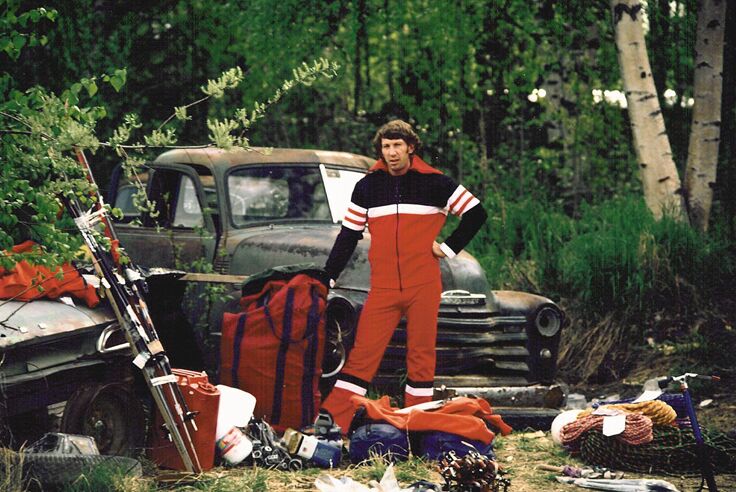

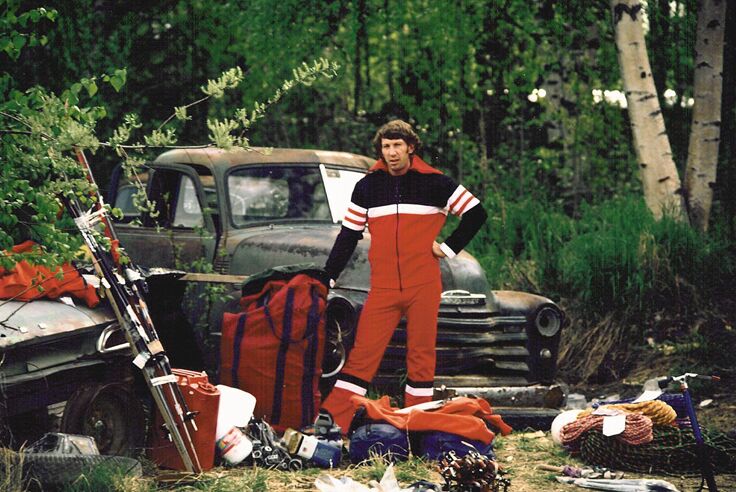

Jim had asked if he could have a tow, and he followed my lead in his Converse high tops, waltzing up the route like it was a Sunday afternoon stroll in the park. When he reached the belay, he looked me sternly in the eye and said, “You know kid, you’ll do alright if you just remember not to step on the rope.” We both broke out in laughter, high-fived, and from that day on we were friends. I never could have imagined the adventures we would share: the first ascent of one of El Cap’s most famous aid routes, an attempt on the east face of Mooses Tooth, fruitless bushwacks to find climbable ice in the Tahoe basin, being involved in a startup clothing company, and of course just the daily perils of living in Tahoe in the early 1980s, a time of big hair and immense indulgences.

It was a long walk through the hospital and my mind wandered back to the spring of 1978, when Augie Klein, Bill Price and I were fixing pitches on the Pacific Ocean Wall to begin the third ascent. This was Jim’s testpeice and reputed to be the hardest big wall climb in the world. We were all under 20, so this caused a stir in Yosemite’s Camp 4.

Jim borrowed the park service’s telescope and hung out in the meadows the day I led the fourth pitch, which previously had almost claimed the life of Rik Riederon the first-ascent attempt. (Jim had gone through several partners before he finished the route in 1975 with Fred East, Jay Fiske, and Billy Westbay.) Jim would check in with our progress each day after we fixed another pitch, asking our opinions and giving us some gear beta. One day before we were ready to commit to the wall, he asked me to take a look at a potential new route to the right of the P.O. Wall. Even from our close vantage point, finding climbable features was like spotting a gnat on a football field from the nosebleed section.

Jim’s personality and grit permeated the entire Pacific Ocean Wall, with stretches of gear barely able to sustain one’s body weight for unfathomable distances. Potential 100-foot falls were present on most of the crux pitches. On the Nothing Atolls pitch, I cleaned after Price led a very long seam of tied-off knifeblades. The final one was rusty, bent, and partially ripped out of the placement. This was the fixed piece that the leader pendulumed off to reach another thin crack 50 feet to the left. Normally, a better anchor (like a bolt) was used for such shenanigans, but the Bird had decided during the first ascent to make it spicy not only for the leader but also the follower, who was staring at a 100-foot swing in space should the piton fail during the lower-out.

After seven days we topped out, and as we returned to the valley floor, Jim met us on the trail, looked straight at me, and asked, “What’d you think?” Instinctively I knew he was talking about the potential new line, not the route we had just climbed, and without hesitation I said, “Let’s go.” Two days later we were fixing pitches on what became Sea of Dreams.

Dale Bard was brought into the mix a few days later while we were unwinding at a party at the employee annex. I really wanted a third person so the belays wouldn’t be so boring. Dale and I had spent most of the prior summer climbing together in Tuolumne, and he was the most qualified partner around for gnarly aid climbing. Besides, he promised he could get Ray Jardine to lend us some of his prototype Friends for the route. Jim was hesitant when I first brought up the idea, saying, “Three can be awkward, especially if tempers flare.” He eventually relented and stipulated that Dale could come if he brought sufficient water and food to supplement what we already had cached on the lower pitches.

Our goal was to put up the hardest route we could, period. Each successive pitch became one in a string of crux pitches. Rarely did the route let up. Just before reaching the Continental Shelf, Jim asked if we could switch pitches so that he could lead the large blank stretch that traversed off the ledge—a 100-foot section that was just blank rock textured like a pimpled-face teenager. His hunch was that it might be spectacular. Knowing full well that he could easily pull rank on me, I firmly protested that we had agreed to swing leads and this one was mine. He thought about it for a few seconds, smiled, and said, “Ok, you’ve got it.” That was so Jim. His respect for his partners, even when they were brash teenagers like myself, empowered greatness. The pitch became known as the Hook or Book. About halfway across the pitch, Jim yelled out, “It’s OK to put a bolt in, you know!” I was in such a trance that I barely paid attention and continued to make the best use of what was available with the 16 hooks on our rack, enhancing rather than bolting. That was also a Bridwell trait. Why blast in a bolt when you can proceed with a little bit of chipping? Although this tactic came under scrutiny on future ascents, we all maintained that orchestrating a pitch to the best of your abilities was better than drilling a bolt ladder.

Throughout the climb, Jim had an uncanny ability to recall the details of where we should go from his study of the potential line through a telescope, even when the next section wasn’t visible to him. In the lead, Dale or I would explain the terrain we were seeing, and Jim would shout up that we needed to head over to a certain flake that led to a seam or some such thing. It was like he was reading a topo etched in his mind.

Jim’s humor also eased the tension of situations that were otherwise dire. On the morning of the Hook or Book pitch, swarms of ladybugs floated up the face. After being bitten a few times, he promptly renamed them “bitch bugs, ’cause ladies don’t bite.” His brand of humor also came out in his professional movie rigging jobs. He once recounted a story about working with Dale Bard to rig a helicopter hull up on a Canadian cliff, from which it was supposed to drop and explode for a scene. Somehow, the pyrotechnics team didn’t catch the cue and the copter didn’t explode but instead plummeted to the ground uneventfully. As the story goes, Mike Hoover, the director, went nose to nose with Bridwell, yelling about how expensive the blunder was. In fact, it wasn’t Jim and Dale’s fault, but rather than defending themselves, Jim simply said, “We may not be much, but we’re the best you’ve got.” These one-liners would just roll out of the Bird’s mouth, with no premeditation. He never caved into subservience. Unfortunately, this also was the reason he didn’t last too long with sponsors.

Although I had spoken with Jim regularly, I hadn’t seen him face to face for at least 20 years. When I entered his hospital room, the beaming smile and glint in his eye brought back a flood of love and memories. His body resembled little more than a scarecrow. He wore a very hip, cool-blue wool hat that matched his blue hospital gown. Jim was always styling.

Immediately we started reminiscing. Rolling in the memories of near misses and telling lies that were truths. He was heartened with all the love from friends that had poured out through visits and phone calls. These really meant a lot to him. We talked about life, family, and love. We exchanged photos of our kids. Jim shared with me that he had accepted Jesus as his Lord and savior when he was 18 and had been ordained, which also legally kept him from participating in the Vietnam War.

We shared two small containers of Häagen-Dazs strawberry ice cream, contraband that I had smuggled in at his request. He was never much for being told what he could and couldn’t do. Delight radiated throughout all 125 pounds of his frail body.

I came back a couple of days later, and Jim was feeling much better. He was totally at peace with leaving the world if the cards played out that way but stubbornly wanting to finish up some writing, chiefly an autobiography. I had worn one of my Bridwell-inspired paisley shirts, which he pawed with an eye of approval. Wanting to encourage his optimism, I offered to send it to him when he was out of the hospital. Although he did get out for a short spell, things went from bad to worse and he was shortly on life support. Jim left us on February 16, 2018.

Jim’s life exemplified pushing the boundaries of his God-given gifts and helping others pursue their limits. He was always focused upon the horizon of what could be and never considered his status quo. For this I am grateful. I miss my friend—even his half-hour political rants and off-the-wall commentaries on humanity. “Those who fail to plan, plan to fail” was one of his favorite Benjamin Franklin quotes. Even in his last days, Jim was certain of the plan.

– Dave Diegelman