Tsaranoro Be, Lalan'i Mpanjaka

Madagascar, Andringitra Mountains, Tsaranoro Massif

More than two decades ago, Bernd Arnold and friends traveled to Madagascar in search of big cliffs. They had hardly any information, only an illusory description of rocks from a missionary. In the Tsaranoro Valley, the party found impressive walls and convinced a local leader to grant them permission to climb. They were late in the year—November 1995—and the daily rain and heat made climbing harder. Still they succeeded, and they named their route after the missionary’s nickname in town: Rain Boto (Father of Franticness). Now there are several campgrounds and over 50 routes at Tsaranoro.

Considering that climbers have been visiting Tsaranoro for decades and the dry season lasts four months, from July to October, one might think that all the good lines have been done. That might be true for most of the less-than-vertical climbs, since the quality and friction of the rock is stunning. However, the overhanging walls are rare and often seep with water.

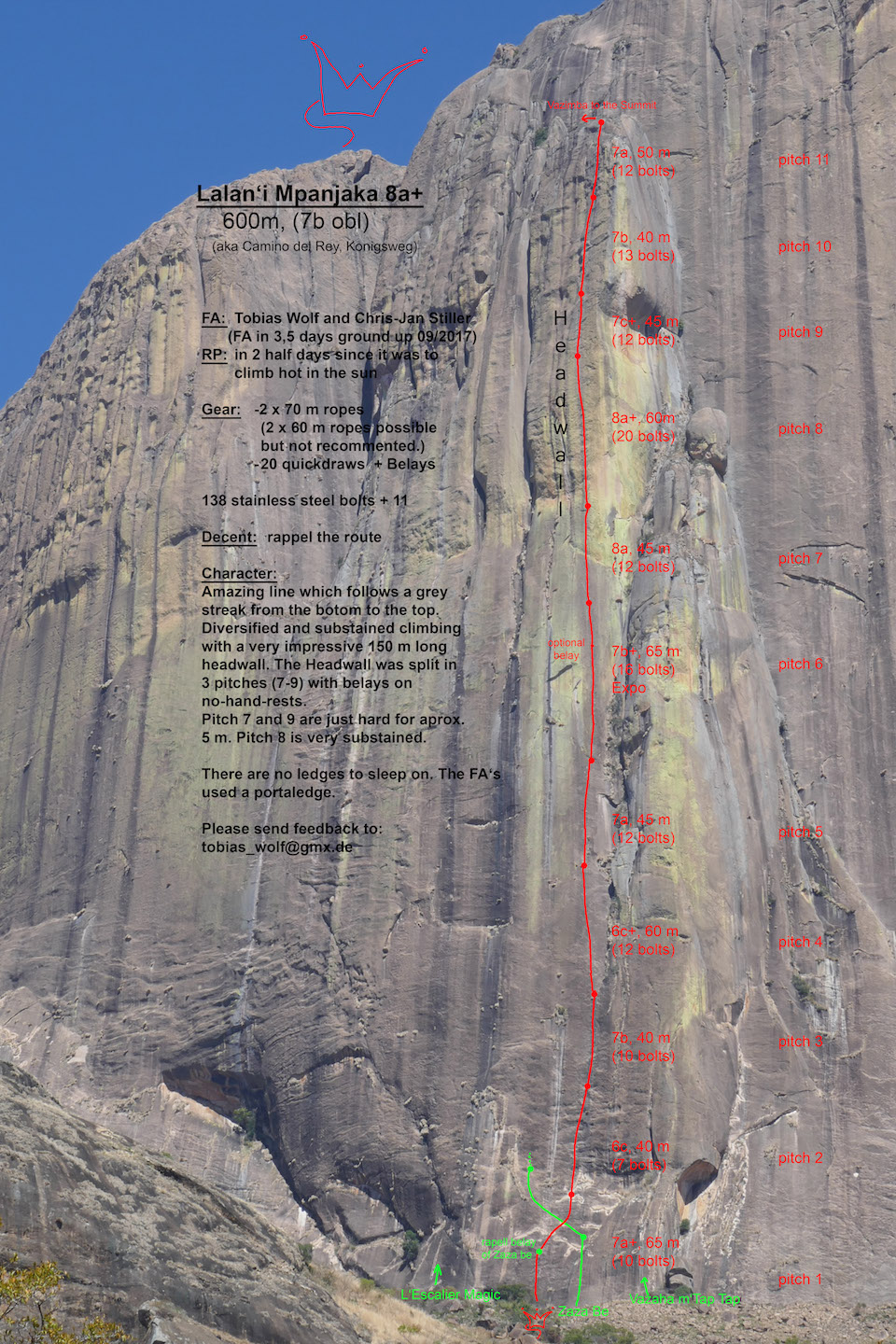

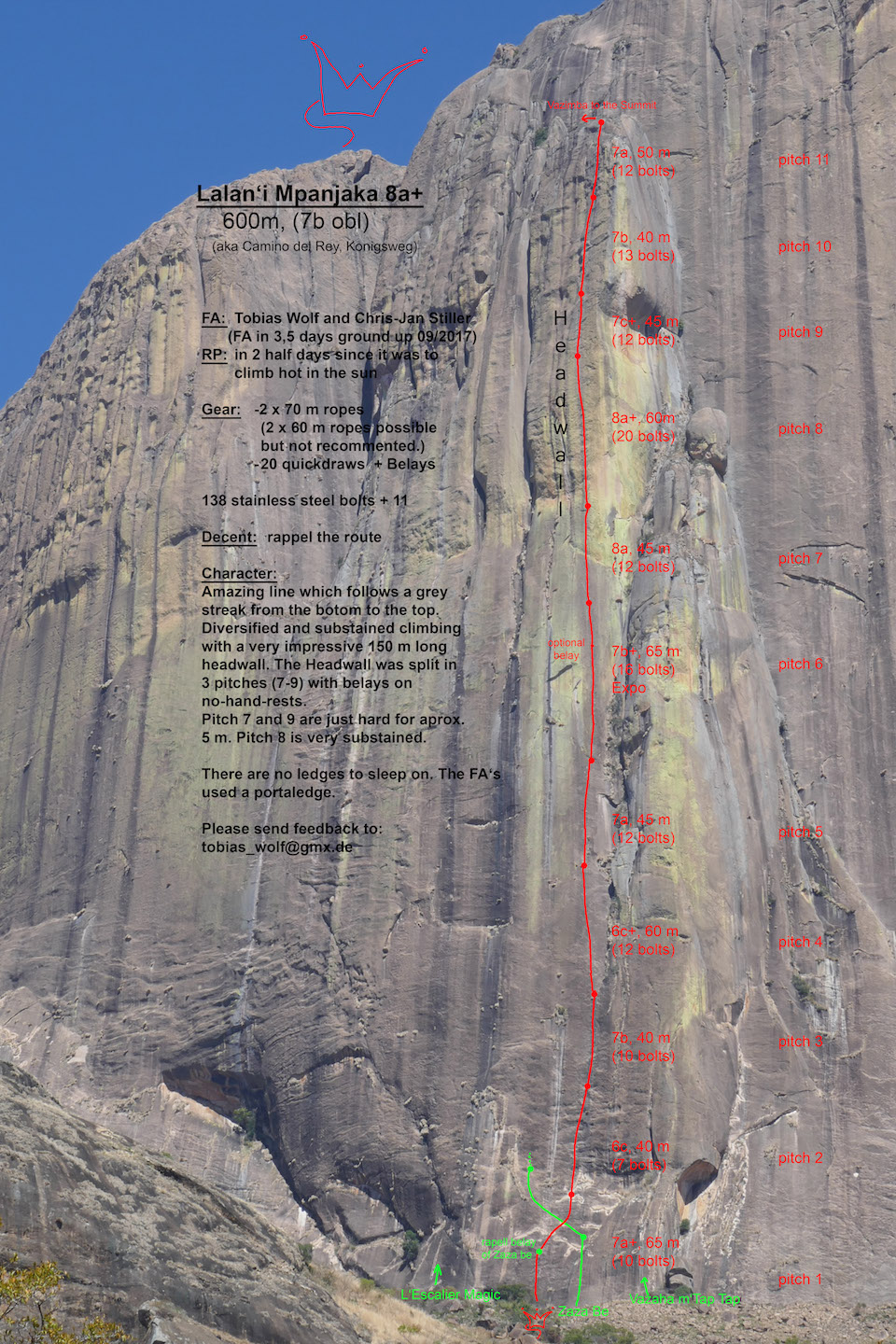

In 2016 I made an attempt to free climb Fantasia (Pellizzari-Piola, 1998) on Karambony, but a blank section stopped that effort. However, while repeating Manara-Potsiny and Zaza Be on Tsaranoro Be, I observed that these routes crossed an overhanging zone at the same height. These routes have just 20m to 30m of overhanging rock, but farther right was a brown streak with a 150m overhanging headwall. Might this line be climbable?

In 2016 I made an attempt to free climb Fantasia (Pellizzari-Piola, 1998) on Karambony, but a blank section stopped that effort. However, while repeating Manara-Potsiny and Zaza Be on Tsaranoro Be, I observed that these routes crossed an overhanging zone at the same height. These routes have just 20m to 30m of overhanging rock, but farther right was a brown streak with a 150m overhanging headwall. Might this line be climbable?

In September 2017 I returned with Chris-Jan Stiller to take a closer look. We both climb in the sandstone towers of the Elbsandstein in East Germany, so we’re used to ground-up bolting. But we were not used to climbing with just one harness, one belay device, and an old 40m half-rope—when one of our haulbags did not arrive in Madagascar, we had to improvise. Luckily, we had prepared for a luggage mishap by spreading our gear across four bags, so at least we could still rig a harness from slings. Our lead rope was missing, but we had a static rope and a 6 mm tagline, which supposedly could hold two falls. To avoid testing this, I asked around in the village for another rope and found an old 8 mm, albeit just 40m long. The first fall on that old rope was scary. Luckily, the rope held, but I fell 10m due to unexpected stretch.

Despite the gear problems, we made quick progress on the first day, climbing 250m and placing 55 bolts for protection and anchors. We fixed our two ropes on the wall and hoped the missing bag would arrive soon. Thanks to Air France, the next day we were able to return to our original strategy: not returning to the ground until the route was completely bolted.

We were now armed with a portaledge and supplies for four or five days. The wall got steeper the closer we came to the headwall, and the more it hung over us the more we doubted that it could go free. The first overhanging meters had just enough holds to be climbable. At home on our sandstone towers we think carefully before placing a bolt, and here we had the same intention. We made sure to place bolts so you can clip them before the hard moves (which at times required placing them a meter lower than the skyhook from which we were hanging). We also eschewed the use of removable bolts—unfortunately, several existing routes in Madagascar have empty holes and don’t mention removable bolts as essential gear.

We needed a full day to finish the headwall. There were three 5.13 pitches in a row, and one stretched to 60m to reach a no-hands belay stance. In several spots one missing hold would have made the line impossible. We spent five days bolting the route and two days redpointing all the pitches.

The route was stunning—we never imagined finding such a perfect line. Our opinion can’t be objective, but we’ve made several hundred first ascents around the world and have not seen another line with such sustained and diverse climbing. Thus we named it Lalan'i Mpanjaka (600m, 11 pitches, 8a+, 7b obl), which means “king line” in the local language. [Editor’s note: This route starts left of Zaza Be (Gamio-Thomas, 2014) and crosses it on the second pitch. Although various published topos suggest otherwise, the German route stays left of Vazaha M’Tapitapy all the way to the top.]

–Tobias Wolf, Germany