Two Solo New Routes on the Ship’s Prow

Canada, Nunavut, Baffin Island, Scott Island

THE VISION for an expedition to Baffin Island had crystalized in April 2016, during a solitary walk near the base of Mt. Dickey in Alaska. Severe conditions had forced Marcin “Yeti” Tomaszewski and me to retreat from the east face. Waiting for the air taxi back to Talkeetna, I ventured out for a walk on the Ruth Glacier, steering a middle path away from the crevasses. My thoughts went back to my 2012 expedition to Baffin Island with Yeti, to the state of mind and evolving harmony that allowed us to achieve the first ascent of Superbalance (VII A4 M7+) on Polar Sun Spire (AAJ 2013). Walking back to camp, I perceived the need to return to the lonesome granite of Baffin Island. An ancient primal nature was calling me.

In February, Yeti and I flew to Ottawa, then far north to Clyde River, on the east coast of Baffin Island. Here we met up with our Inuit friend, the trusted outfitter Levi Palituq. We packed the cargo sled and snowmobiled five hours to the base of the huge, unclimbed Chinese Wall, at the mouth of Sam Ford Fjord, and established camp on the landfast sea ice. We were prepared for typical winter temps of -30°C, but instead encountered -50°C (-58°F) and ferocious winds that made walking almost impossible. After ten days with no improvement in the weather, we knew there was no chance for an ascent within the winter season. Yeti’s portion of the expedition had come to an end, but I planned to stay. He was reluctant to leave me in these hazardous conditions, but I told him not to worry. I had planned the second part of the expedition to be solo, and I was already centered on being alone.

We called the outfitter for a snowmobile pickup, and Yeti returned to Clyde River with our sat phone and broken photovoltaic charging system. I realized, OK, now I am really alone, no chance to communicate with anyone. No imagining that I could call for help if attacked by a hungry polar bear. I became very calm, it was simple. I felt a wave of freedom.

Levi returned to meet me at the base of Chinese Wall three days later, on March 14, with a new sat phone. We snowmobiled another 40 miles to the north and west to Scott Island, deep into polar bear territory. Levi explained a few techniques on how to avoid becoming lunch. “If you try to run from a bear, he will catch you in a second, you would have no chance,” he said. “You need to show him you are brave and ready to fight.” It was scary, but I was calm because there was no choice.

Levi motored the snowmobile eight hours back to Clyde River, and I was left to make camp on the frozen sea at the base of the north face of Ship’s Prow. Temperatures had warmed to -35°C (-31°F). Stillness permeated everything. This is the place, I thought. I don’t need to meditate, I am in the meditation, just being here.

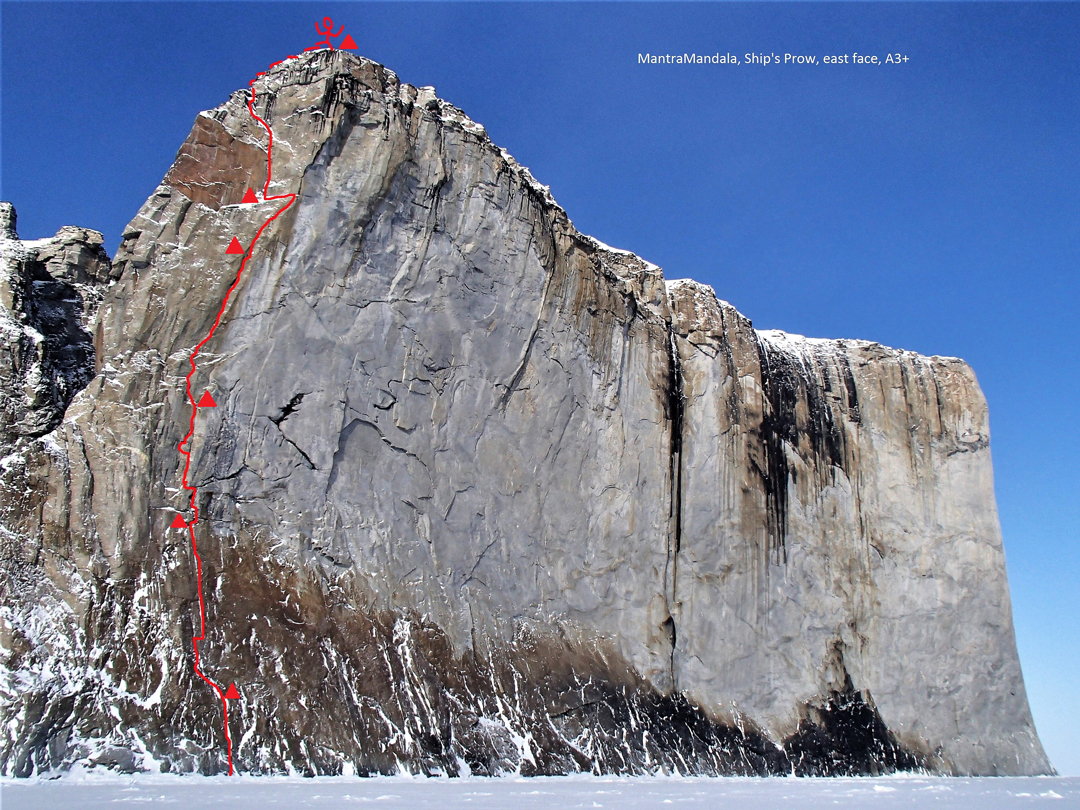

For days I examined the north face of Ship’s Prow. I visualized a new line, but the severe low temperature prevented climbing. I didn’t want to wait, but nature asked me. So I ventured out on walks, studied the east face of Ship’s Prow, and found it was warmed by some direct sunlight. Temps of -20°C would allow me to climb there for three or four hours per day.

While searching the east face, I discovered a possible break in the wall’s defenses, saw my chance for an attack. I realized I was still thinking like a man from civilization, mistakenly seeing the wall as something to be conquered. As my vision opened, the big wall became an association of intriguing granite, concise sunshine, steady gravity. Nature offered an ancient earthly rhythm, allowing me a chance to play my improvisation.

I made a plan to climb with no fixing to the ground, no returning to camp. Only the essentials, the nature of the wall, a couple of haul bags, me and my mind.

After 17 days I’d finished the route MantraMandala (450m, VI A3+), the first line up the east side of the Ship’s Prow. I climbed in capsule style, without fixed lines to the ground or bolts, rivets, or copperheads. I needed to drill six holes for bat-hook placements. Just before this Baffin Island expedition, I had completed a seven-year writing project, and this route name, MantraMandala, is from a chapter in my new book, Written in the Rings (Zapisany w kregach in the Polish language).

Standing atop the Ship’s Prow, my thoughts were already fastened on the north face route. I returned to the snow and sea ice at the base of the east wall and found polar bear prints all around my sled. I walked back to camp at the base of the north wall. Paw prints again, all around my tent, but nothing was disturbed. Not even the food. Winds were building, snow was falling—it was a good time to rest. The next day, I carried the second bag from the wall back to camp. Two days for sorting food and gear and repacking.

|

|

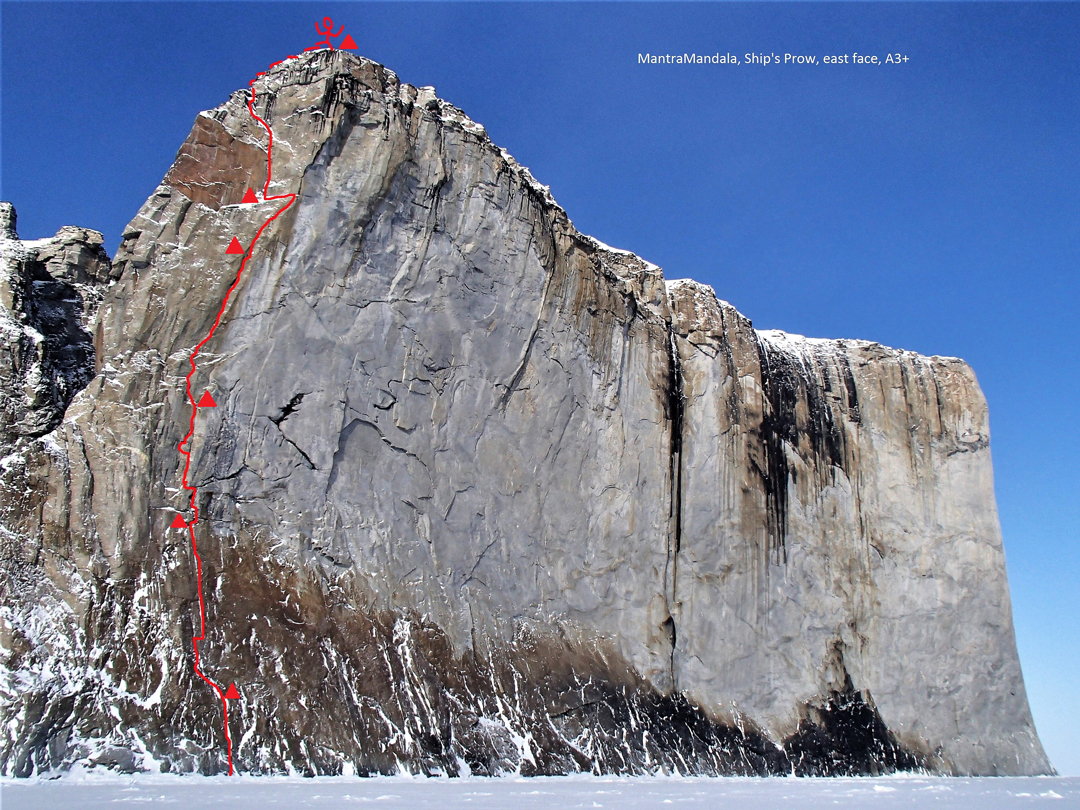

| The north face of the Ship's Prow on Scott Island. Red line: Marek Raganowicz’ new route Secret of Silence (600m, VI A4). Green line: The Hinayana (600m, VI 5.8 A3+, Mike Libecki solo, 1999). |

Still snowy, windy, temps of -35° C. I decided I needed to fix the first few pitches for the longer, more technical route on the north face. Bears investigated my camp again. I scared them away, but they were back in a few hours. The bears carried off a bag and a rope that night; the next day they played with the fixed line hanging down from the wall. Levi had advised me to pack a rifle for emergency self-defense. I kept it next to me in the tent and tied it to the end of the rope when jugging the fixed line.

I spent nine days on the north face route. I used a full assortment of beaks, cams, and nuts. No copperheads, no drilling. Secret of Silence (600m, VI A4) is my cleanest line. [This route rises to the right of the line climbed by Mike Libecki during his solo first ascent of the north face of Ship’s Prow. Libecki established The Hinayana (600m, VI 5.8 A3+) in the spring of 1999.]

The experience of silence in Baffin Island was deeper than anything I’d experienced before in my life. Beyond normal understanding or description, beneath the stillness I sensed a secret. Seven weeks of immense solitude—I had become a bit of the wild of Baffin Island.

On May 3, Levi arrived along with a group of trekkers and a friend of mine. I heard names, shook hands, smiled for photos. Culture shock on the sea ice. Two weeks later, I was sitting by the warm fireplace at home in Inverness, Scotland, attempting to assimilate.

– Marek “Regan” Raganowicz, Poland, as told to Earl Bates, USA