Avalanche

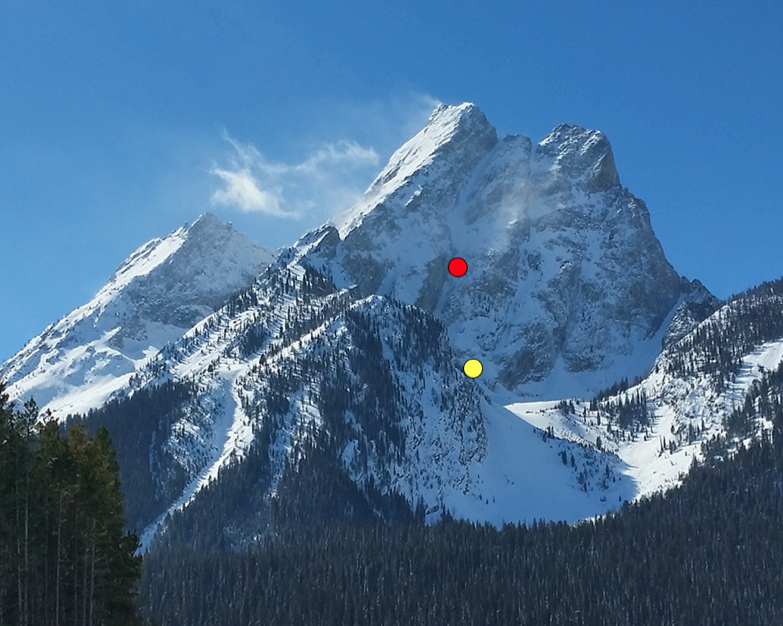

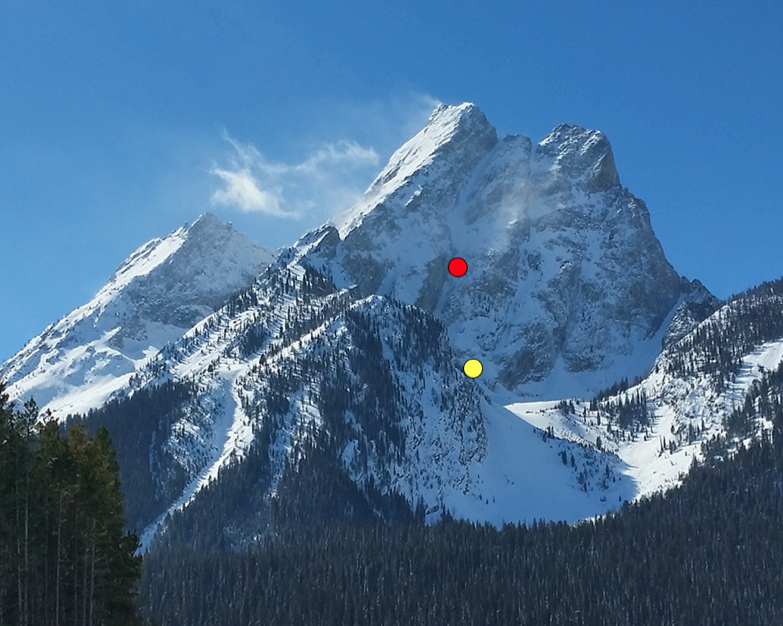

Wyoming, Grand Teton National Park, Mt. Moran, Sickle Couloir

On May 17, four ski mountaineers were involved in an avalanche in the Sickle Couloir on the northeast face of Mt. Moran (12,605 feet). Three of the men were carried 500 to 600 vertical feet in the slide. They came to a stop on the surface, but one died at the scene as a result of injuries and a second died after being flown from the site by rescue helicopter. A third had lesser injuries.

The Sickle Couloir gains about 3,000 vertical feet and is given a mountaineering rating of Grade III 5.4. The four men in this incident were all very experienced ski mountaineers and were well equipped.

At 6:15 a.m., after crossing Jackson Lake by boat, the four men began their ascent to the Sickle Couloir Basin on foot. They did not encounter any snow until they arrived in the basin at approximately 7,500 feet. Here, they noted evidence of widespread wet avalanche debris that had been deposited sometime in the previous 24 hours. They discussed this observation and concluded that most of the significant recent snowfall would have been flushed from the SickleCouloir, thus reducing the avalanche hazard. However, due to cloud cover, they were not able to see the conditions above 10,000 feet.

They continued upslope on skis until they switched to crampons at the base of the couloir and began the actual climb unroped. The bed surface of the snow was very hard, with a thin, one-to two-centimeter layer of new snow lying on top. All four were climbing with a Whippet (self-arresting ski pole grip) in one hand and a normal ski pole in the other. After climbing approximately 600 feet, the group stopped for a short food and water break at an elevation near 9,900 feet. All four climbers were within five to six feet of each other.

The party heard potential avalanche activity above them. Seeing the oncoming snow, one of the surviving skiers moved slightly left and gripped the Whippet that he had forced into the firm snow. As the snow was hitting his right foot, he recalled the snow as being fairly slow-moving and relatively shallow (less than boot-top deep). He also felt that it took approximately two to three seconds for the snow to pass. After the snow had passed, he looked up to see that the others were gone.

The slide carried the other three through some narrow, very steep terrain where they most likely sustained their traumatic injuries while bouncing off the rock and firm snow. None of the three was buried for significant time during the event. The remaining skier descended immediately and began first aid. A call was made to 911 at 9:33 a.m. Continued snow sloughs forced him to move the most seriously injured skier to a safer location before help arrived. A large rescue effort ensued. Despite difficult flying conditions, all members of the party had been air- lifted from the scene by 2:30 p.m.

ANALYSIS

The Sickle Couloir is a committing climb and ski descent in the best of conditions. An unroped fall in the steep section of the couloir, either climbing or skiing, would likely be unstoppable.

In the preceding weeks, multiple storm systems had deposited new snow at the higher elevations in the Teton Range, with rain at the lower elevations. According to the Bridger Teton Avalanche Center’s weekly snowpack summary, the most recent storm (May 7 to 9) had deposited a total of 21 inches of new snow, with over two inches of moisture, to higher elevations. Another storm system deposited 10 inches of new snow and an inch of water at the Rendezvous Bowl weather station during the period from May 15 to 16. While the party did experience light snowfall during their ascent of the couloir on May 17, the firm conditions in the couloir served to confirm their assumption that some snow had already slid and that the hazard was reduced.

The Sickle Couloir, and the terrain that feeds it, would concentrate any old or fresh snow that avalanched. While the avalanche that occurred was not large, it did entrain enough snow in the steep couloir to cause three of the four to fall.

A party’s decision to go into the mountains is personal. Factors to be considered are the team’s experience, abilities, fitness level, environmental conditions, and the acceptable level of risk exposure. Reports and evidence indicate the members of this team had the experience, ability, and fitness for the objective.

Fatal avalanche and/or ski mountaineering accidents seem to be on the rise in Grand Teton National Park. One to two of these events have been experienced each year for at least the past five years. Not only are these events traumatic for the parties and families involved, they can also expose rescuers to significant, if not extremely, hazardous conditions. While some amount of exposure is ever present in the mountains, mountaineers and rescuers alike must employ objective, prudent, and conservative judgment to minimize that exposure where possible. (Source: National Park Service Search and Rescue Report