The Dawn Wall

The Long Struggle For The World's Hardest Big-Wall Free Climb

Standing at the base of the Dawn Wall on December 27, 2014, I attempt to break the nervous tension. “It’s the low-pressure push,” I say with a grin. I know it’s bullshit. Once we start, we’re going to the top. “One pitch at a time,” Tommy responds. I nod and start climbing.

Standing at the base of the Dawn Wall on December 27, 2014, I attempt to break the nervous tension. “It’s the low-pressure push,” I say with a grin. I know it’s bullshit. Once we start, we’re going to the top. “One pitch at a time,” Tommy responds. I nod and start climbing.

Six years earlier, I was sitting on top of a 55-foot boulder at the Buttermilks in Bishop, California. Just a few moments before, I’d been 45 feet off the deck, ropeless, on my most ambitious highball first ascent to date. For the past two years, I’d constantly put myself in positions like this. I was obsessed with pushing the standards of highball bouldering, rolling the dice with each sketchy first ascent. Ambrosia pushed the bar even higher, not just blurring the lines between highball and solo but crossing it. To continue meant becoming a free soloist, and I was unwilling. Not only did I need a new project, I needed a new discipline of the sport.

The climbing film Progression, released in late summer of 2009, featured both Ambrosia and Tommy Caldwell’s new big-wall free climbing project. When I saw the closing scene of Tommy’s segment, I heard an invitation: “I look at this next generation of climbers doing things on the boulders and sport climbs that I can’t conceive of. If they could apply that kind of talent to the big walls, that’s what it would take to free climb this project. Even if I can’t climb this, I want to plant the seed for someone in the future to come and inspire us all.”

Was this the opportunity I was looking for? I was completely unqualified. Tommy and I had only climbed together one day. I had never climbed El Cap. I wrote Tommy an email out of the blue, asking him if he needed a partner for the fall season. To my utter shock, he said yes.

A few months later, in October 2009, I met Tommy in El Cap Meadow for the first time. Little did I know this was the first of hundreds of such rendezvous. I was nervous but ready for anything. I had to ask Tommy where the line went—when I looked to the right of the Nose I couldn’t see any features to climb. Our plan was to hike heavy haulbags to the top of the wall. For the next five hours, my face was only a few feet from the ground, bent under the load. On top of the labor of the hike, Tommy’s dad was crop-dusting me the entire time. When we got to the top, well after dark, I dropped the pig on the ground and felt endorphins rush to my head. “That felt good!” I exclaimed, stretching my arms overhead and looking up at the stars. I would later learn how much these three words influenced Tommy’s perception of my grit and durability.

A few months later, in October 2009, I met Tommy in El Cap Meadow for the first time. Little did I know this was the first of hundreds of such rendezvous. I was nervous but ready for anything. I had to ask Tommy where the line went—when I looked to the right of the Nose I couldn’t see any features to climb. Our plan was to hike heavy haulbags to the top of the wall. For the next five hours, my face was only a few feet from the ground, bent under the load. On top of the labor of the hike, Tommy’s dad was crop-dusting me the entire time. When we got to the top, well after dark, I dropped the pig on the ground and felt endorphins rush to my head. “That felt good!” I exclaimed, stretching my arms overhead and looking up at the stars. I would later learn how much these three words influenced Tommy’s perception of my grit and durability.

The next morning was my initiation to pioneering a big-wall free climb. My job was to rappel off the top, do 100-foot rope swings from side to side, and figure out how the last four pitches of the climb would reach the summit. I hand-drilled my first bolt. I hollered into the wind with 3,000 feet of air beneath my toes. I showered dirt onto my face as I cleaned mossy finger cracks. As I Mini-Traxioned what would become the last pitch of the climb, I thought about what it would feel like to grab the top of the wall and have it matter. It was only day one, but I was already imagining how amazing the last day would be. I was in heaven. That is, until I tried to lead a pitch.

I was gripped. I quickly found that this style of climbing was different from anything I was used to. I was appalled by the protection. We were in aid climbing territory. No man’s land. We had to adapt our style to the canvas, which meant making use of every scrappy piece of aid protection already in the wall and adding no bolts unless absolutely necessary. Tommy tried to assure me that “beaks are like bolts,” until I zippered some out of the wall when I fell.

Over the next six years, every one of my 350-plus days on the wall was an education. Tommy had spent the past 18 years climbing on El Cap, and I needed every day I could get in order to catch up to his level of mastery. I was a kindergartener in a Ph.D. class. My education never stopped, right up until the day we started our final push.

Technically, day one of the route is the easiest. Every day after this, we will have to climb at least one pitch of 5.14 until we get through pitch 16. The first four pitches pass smoothly, but pitch five makes me fight. California has just experienced two solid weeks of rain, which means the entire crux of this 5.12d pitch is wet. Pulling onto Anchorage Ledge, pumped and drenched, I’m satisfied with my aggression. I know I want it.

With the positive momentum from day one, we roll through our first week on the wall. Another day, another pitch of 5.14. Our mood is light and energy is high. Day four brings a frigid windstorm and our first rest day. These days are as much about giving our mind a break as healing our bodies. It’s a marathon, so it’s important to stay as fresh as possible. To pass the time, Tommy and I pile into a portaledge with videographer Brett Lowell, sip bourbon, eat chocolate, and watch The Wolf of Wall Street. We laugh awkwardly at the crude humor and nudity. “I feel like I need a shower after watching that,” Tommy jokes. In stitches, we forget all about the frigid wind outside and the intensity of the effort we face.

On day six we reach pitch 14, the hardest on the route. Slicing horizontally across the wall from right to left, the pitch is characterized by three vicious boulder problems with rests between each. Six weeks earlier, I fell off the last move of the pitch, so I know I can do it. But I still haven’t. Tommy sent this pitch on the same day I fell off the last move, and he’s climbing stronger than I’ve ever seen him. It feels like there’s an inevitability to his success. For me, there’s the inevitability of the battle, the pressure, the very real fact that now is the moment I have to do what I’ve never done before.

Honestly, I wasn’t that close to climbing the Dawn Wall when we began. Of the six 5.14 pitches, I had only done the two easiest ones. Not only that, but the myriad 5.13+ pitches above the crux were a big question mark for me. Four years earlier, it had been the 5.14b stemming corner and face traverse of pitch 12, the Molar Traverse, that shut me down. But on the last day of 2014 I clipped the anchors within a few attempts, shattering doubts that had defined my reality since 2010. “I never have to do pitch 12 again!” I exclaimed with shock and relief. This breakthrough was critical for my confidence.

Now, January 1, we face pitch 14. Of all the pitches on the Dawn Wall, I have spent the most time working on this one. I know how it should feel. But on my first three attempts, I’m plagued by the finicky first crux, with a microscopic hold on which my left foot stubbornly refuses to stick. It’s dark out. We climb after the wall goes into shade and well into the night, in midwinter, because the holds on these crux traverse pitches are too small to use when the temperature is above 45°F. The ironic thing about climbing at night is that the headlamp casts a shadow below even the smallest dimple on the wall, making our footholds appear more positive than they are. In the flat daylight, they look like porcelain. On my fourth attempt the left foot sticks, and after a few breathless moves I’m through the first crux and staring at the final move. Last time I managed the crux I rushed the move to the belay. I won’t make the same mistake twice. I force myself to hesitate and focus on the final edge guarding the anchor before committing.

Now, January 1, we face pitch 14. Of all the pitches on the Dawn Wall, I have spent the most time working on this one. I know how it should feel. But on my first three attempts, I’m plagued by the finicky first crux, with a microscopic hold on which my left foot stubbornly refuses to stick. It’s dark out. We climb after the wall goes into shade and well into the night, in midwinter, because the holds on these crux traverse pitches are too small to use when the temperature is above 45°F. The ironic thing about climbing at night is that the headlamp casts a shadow below even the smallest dimple on the wall, making our footholds appear more positive than they are. In the flat daylight, they look like porcelain. On my fourth attempt the left foot sticks, and after a few breathless moves I’m through the first crux and staring at the final move. Last time I managed the crux I rushed the move to the belay. I won’t make the same mistake twice. I force myself to hesitate and focus on the final edge guarding the anchor before committing.

Back at the portaledge 45 minutes later, I send my girlfriend, Jacqueline, a text: “Babe. It’s done.” It’s not even 8 p.m. and the hardest pitch on the Dawn Wall is in the bag for both of us. The mood is light and celebratory as we go about our evening ritual of washing our hands, making tea, taking a nip of bourbon, and cooking dinner.

Whereas I had been obsessed with learning the nuances of pitch 14 over the years, I had largely avoided pitch 15, the second hardest on the route. Something about the nature of the climbing always put tension in my chest. I could never find a rhythm on it. When Tommy sent pitch 15, two years earlier, it had dropped down our priority list. I would always justify spending time on some other pitch. Well, there was no avoiding it now. This second traversing pitch is broken into two distinct sections: a 60-foot 5.13c to a big rest, followed by a vicious iron-cross boulder problem on razor blades. Prior to the push, I had never even linked from the start of the pitch to the rest. But I had done the boulder problem on many occasions.

The week that follows is the most intense of my life. Tommy swiftly dispatches pitch 15 after one warm-up burn. With the index and middle fingers on my right hand taped to protect the worn-out skin from splitting open even more, I give four all-out efforts before my power and precision deteriorate. Back at camp, I dismiss the failure. “It’s only natural that this route puts up a fight,” I shrug. The key takeaway from first round is how much harder the crux feels with taped fingers.

Round two the very next morning confirms this. After one attempt, it’s clear that I have no chance at the pitch as long as two fingers are taped. I force myself to rest the remainder of the day, and the following one as well, while my skin heals. Meanwhile, Tommy has gone on to climb the Loop Pitch, which circumnavigates an 8.5-foot dyno on pitch 16 that has given him a lot of trouble. The Loop partially reverses pitch 15, downclimbs 50 feet, and then climbs 60 feet up an adjacent corner on the left to where the dyno ends. With the Loop Pitch complete, Tommy only has one more pitch of 5.14 left on the entire route.

On day four on pitch 15 I am full of hope and determination. If I can just send tonight, I’ll be caught up with Tommy, causing no delay. The skin on my right index finger has healed just enough to climb without tape. I probably have two or three attempts before it splits again. Every go has to count. After four demoralizing close attempts, the tip of my right index finger ruptures. “Fuck!!!” I scream into the night, hanging at the end of the rope. Tommy, Brett, and photographer Corey Rich are all silent.

Back at the belay, my fat, frustrated thumbs tap out a single-word text to my girlfriend. “Devastated.” I press send and stuff my phone back into my pocket. Blood seeps through the tape on my fingers as I pull on my gloves. I rappel back to camp, 200 feet below. My eyes, once laser focused on every detail of the granite, take on a thousand-yard stare as we prepare dinner. Pasta. Again. Two more rest days needed. Again.

Inside the sleeping bag, my thoughts churn. Maybe I should just throw in the towel and support Tommy to the top. I don’t want to be the guy that almost climbed the Dawn Wall. What’s a few more rest days if it means success? I will rest. I will try again. I will succeed.

The sound of falling ice hitting my portaledge wakes me around 6:30 a.m. The ice isn’t too big; it sounds like hail, but more sporadic. Nearly all the risk on the wall is in our control, but ice falling from the rim is more like roulette. It will be another hour before the sun reaches us, so I try to fall back asleep. The hardest part of this project isn’t the climbing, it’s the time between the climbing. The waiting game. We’ve already been up here for more than 10 days: plenty of time for focus, confidence, and determination to crumble.

The sound of falling ice hitting my portaledge wakes me around 6:30 a.m. The ice isn’t too big; it sounds like hail, but more sporadic. Nearly all the risk on the wall is in our control, but ice falling from the rim is more like roulette. It will be another hour before the sun reaches us, so I try to fall back asleep. The hardest part of this project isn’t the climbing, it’s the time between the climbing. The waiting game. We’ve already been up here for more than 10 days: plenty of time for focus, confidence, and determination to crumble.

After breakfast, we check in with our loved ones. Tommy calls his wife, Rebecca, in Colorado and shares the news, both good and bad. He sent the pitches he wanted to the previous night. I didn’t. I can feel the nervous energy coming through the phone. Rebecca is wondering if Tommy will push on without me. She’s wondering how long he will wait. Have we had “the conversation” yet?

The conversation comes up after breakfast. Tommy keeps it simple: “Hey, man, the weather forecast is amazing. I’m going to keep going until Wino Tower but stop there. I’ll go into full support mode at that point for as long as it takes for you to catch up. There’s nothing worse I could imagine than finishing this climb without you.” Right away, I feel some of the pressure dissolve.

Tommy will climb and I will head up our network of fixed ropes to belay him as he pushes higher. It’s hard for me to feel excited for his progress. Likewise, he’s probably holding back some excitement after each pitch so as not to discount the battle I’m still waging. It’s an unspoken, delicate balance of support, but also distance. We don’t talk about it.

Like a machine, Tommy reaches Wino Tower. He will certainly send the Dawn Wall. One hundred and eighty feet below, I’m happy for him, truly. But I’m also hollow. Tommy is only two days from the top—he could probably do it in one. I have a pitch of 5.14d, a 5.14c dyno, a 5.14a corner, and three pitches of 5.13+ before I catch up. Jesus.

Two days later, January 9, I wake feeling calm. Today is my day. The portaledge fly flaps in a cold updraft. A soft, gray light sits in the Valley—it’s the one overcast day we’ve seen in the forecast. One way or another, a conclusion is coming and I’m at peace with it. Today is our 14th day on the wall. Today, I will either send this pitch or sacrifice my dream to make sure Tommy realizes his.

I start my preclimb routine, sanding any abrasions off the soles of my climbing shoes. Then I do the same for my fingers. Next I coat my split finger in superglue and begin an elaborate, weaving tape job with a special brand of Australian tape donated by Beth Rodden. I tie in with the perfect figure-eight, with the tail passed back down into the knot. I lace my shoes carefully. A jumar goes on the right gear loop of my harness. Gri-gri on the left. I’ll need them both to get back to the portaledge if I fall. Last, I strip my top layers down to the same green T-shirt I’ve been wearing from day one.

This isn’t any shirt. It’s Brad’s shirt. Really, it’s the reason I’m even on this wall. Since I was 16, Yosemite has been a place of inspiration and wonder. But this year the Valley held two very real ghosts, neither of which I had wanted to confront.

This isn’t any shirt. It’s Brad’s shirt. Really, it’s the reason I’m even on this wall. Since I was 16, Yosemite has been a place of inspiration and wonder. But this year the Valley held two very real ghosts, neither of which I had wanted to confront.

The first was the ghost of some rough times in my relationship with Jacqui. Last October, for reasons I still don’t fully understand, she pressed pause on the relationship. We’d since come back together, stronger, but the Valley held an emotional residue from that experience. It represented the feeling of losing a person and a future that had seemed perfectly, joyously inevitable. Second, the Valley held the ghost of my dear friend Brad Parker, who fell to his death on the Matthes Crest in Tuolumne on August 16, 2014. His passing was the first time I’ve experienced true grief. True loss. I wasn’t alone either. Our whole tribe was crushed—every person he inspired with his bright, daily, “epic” approach to life.

In September, mere weeks before I was to meet Tommy to begin the Dawn Wall season, my heart had been fragile and uncommitted to the impending battle. I trained halfheartedly by bouldering and hangboarding in the gym a few times per week. Before I could feel the uplifting burn of inspiration, I would have to turn my two ghosts into allies.

One night in mid-October, while I was up on the wall attempting to prepare for our push, Brad’s girlfriend Jainee texted me that she too needed to confront the emotional trauma of Yosemite. The last time she’d been here, she drove in with the love of her life and drove home alone. I had felt utterly helpless in the wake of Brad’s passing. But surely I could help Jainee by taking her climbing. Over the next two days, Jainee and I climbed nothing but easy Valley classics. For years, training and the cloud of pressure around the Dawn Wall had defined my experience with climbing. But for these two days it was pure joy. The experience washed away the memory of emotional trauma and turned grief into celebration. It’s exactly what I needed.

Around this time, we started the B-Rad Foundation in Brad’s name and designed T-shirts with original art based on a drawing Brad had done on the dirty window of his truck’s camper shell. Since beginning the final push on the Dawn Wall, I’ve been wearing one of those shirts every day. It’s the reason I’m even on the wall again. If I’m lucky it will be the reason I stand on top as well.

Around this time, we started the B-Rad Foundation in Brad’s name and designed T-shirts with original art based on a drawing Brad had done on the dirty window of his truck’s camper shell. Since beginning the final push on the Dawn Wall, I’ve been wearing one of those shirts every day. It’s the reason I’m even on the wall again. If I’m lucky it will be the reason I stand on top as well.

The moves between the belay ledge and the midpoint rest on pitch 15 are nearly automatic at this point. Despite the highly technical climbing I find a flow. Shaking out on the jug, I alternate holding my hands to the wind, using the icy updraft to harden the calluses on my fingertips. When my heart rate falls to near resting rate, I turn my mind from relaxation to razor focus. A few sharp exhales prep my body for what I’m about to make it do.

The last ten times I’ve been at this spot the result has been the same. Something has to change. I’ve decided to revert to a foot sequence from earlier in the season. The difference is subtle, but while holding the crux iron cross, from fingertip to fingertip, I feel the difference I’ve been seeking. My right foot is secure. Anxiety is replaced by confidence. Trembling is replaced by control. I’m through the crux, with one more bolt of insecure climbing to negotiate. As I grab one of the final crimps, I see the tape on my index finger saturated with blood. Doubt lasts only an instant. Moments later, everything is silent except the strong wind in my ears.

For a few moments there’s no celebration, just breathing. Did that just happen? I do a last few moves and clip the anchors at the no-hands stance. My scream reverberates down to the meadow, and cheers echo back up to the wall. Yes, that just happened.

A collective breath is released. Not just by me and by Tommy, but at this point by millions of followers. Momentum is a powerful force, and when nervous anticipation turns into universal celebration, everything shifts. The tide is coming in and I ride it upstream.

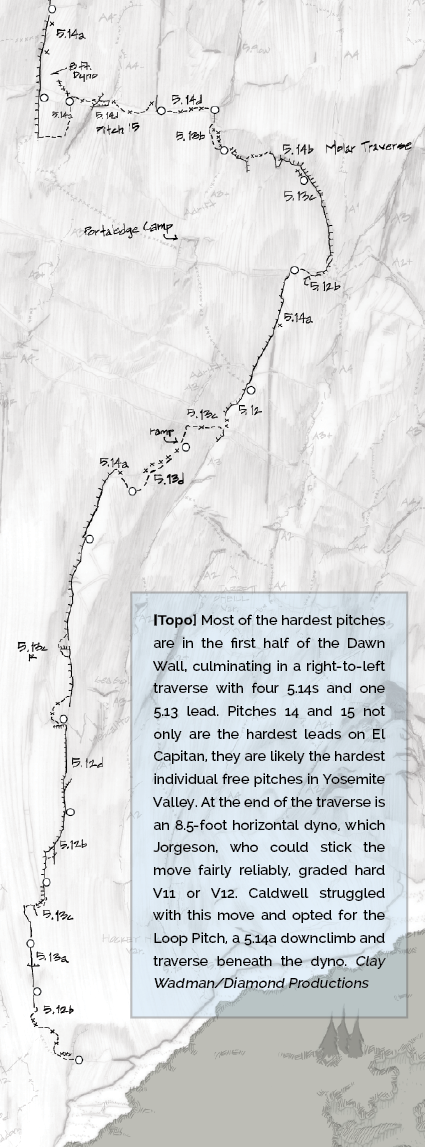

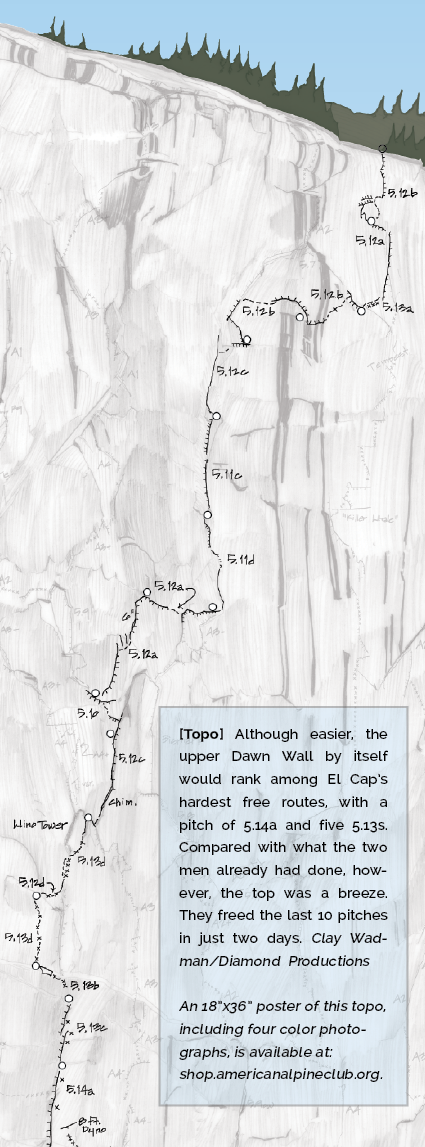

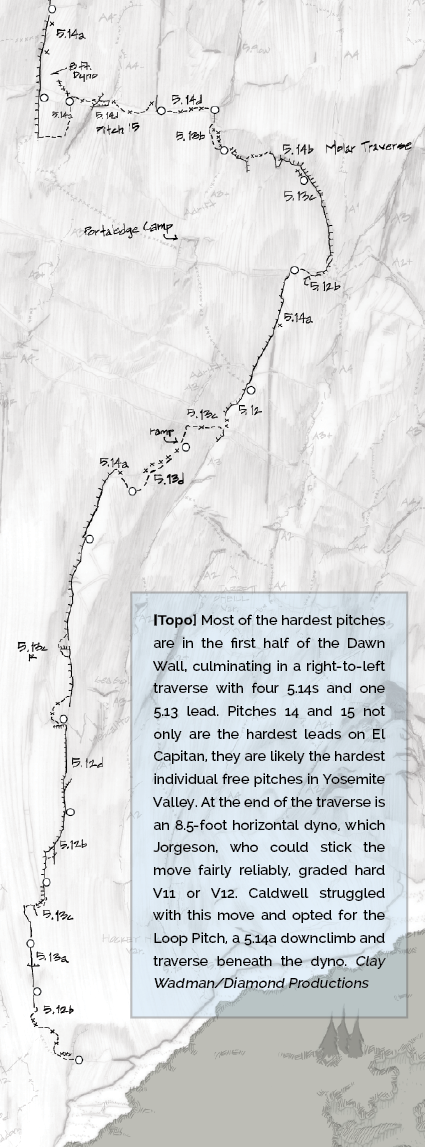

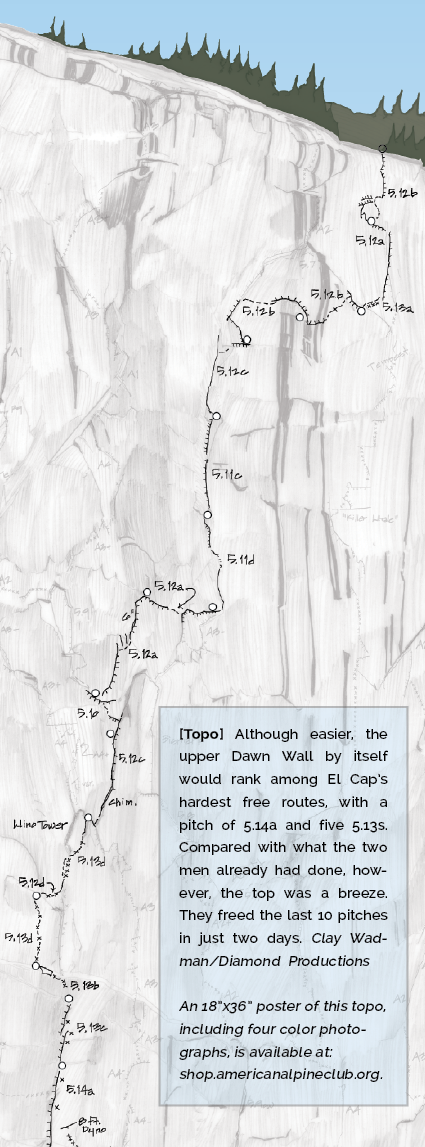

Summary: First free ascent of the Dawn Wall (32 pitches, 5.14d), a free link-up of Mescalito and the Wall of Early Morning Light, plus portions of Adrift, Tempest, and previously unclimbed sections of the southeast face of El Capitan. Tommy Caldwell began working on the route in 2007 and was joined by Kevin Jorgeson in 2009, spending 8 to 10 weeks each year on the climb. They redpointed the full route December 27, 2014–January 14, 2015, with each climber leading or following every pitch free (the two led different variations on pitches 16 and 17).

About the Author: Kevin Jorgeson, 30, lives in Santa Rosa, California.

The American Alpine Club has produced an 18" X 36" commemorative Dawn Wall poster, featuring Clay Wadman's ultra-detailed topo of the full route and four great photos from the climb. All proceeds benefit the American Alpine Journal. Limited-edition signed posters also available. See details and order posters here.