Soul Garden

A Gift From Sean Leary

“Right now your grief is this giant gaping hole with sharp edges, but as you move forward in life the edges soften and other beautiful things start to grow around it…flowers and trees of experiences. The hole never goes away, but it becomes gentler, a sort of a garden in your soul, a place you can visit when you want to be near your love.”

“Right now your grief is this giant gaping hole with sharp edges, but as you move forward in life the edges soften and other beautiful things start to grow around it…flowers and trees of experiences. The hole never goes away, but it becomes gentler, a sort of a garden in your soul, a place you can visit when you want to be near your love.”

These are the words Sean Leary wrote to comfort a friend, who like Sean, had lost the love of his life. Now Sean is gone, and the hole in my heart is still sharp and jagged. But before Sean left us he gave me a seed to begin growing in my soul garden.

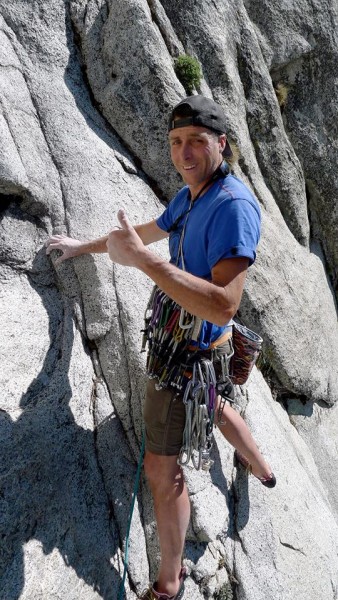

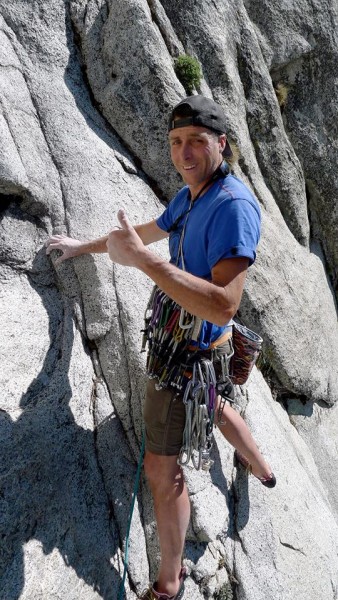

I first met Sean in Yosemite Valley. It was 1994. He was 19 and I was 21. He had long hair, pants with holes in the butt, and a big-ass grin. With carefree confidence in himself and others, he was always game for anything, no matter how big, how far, or how late in the day. Sean was a true force of nature: perpetually psyched, physically gifted, and completely uncompromising with anything that pulled him away from his dreams. This mindset would allow Sean to pull off many unbelievable feats in the Valley, including climbing El Cap three times in a day, freeing El Cap and Half Dome in a day, and climbing the Nose in record speed. Sean would also take these skills into the greater ranges, establishing new routes on some of the biggest walls in the world.

Sean’s Mt. Watkins project began in 2012, almost two decades after our first meeting. It was Sean’s first time free climbing the classic south face route, with Jake Whittaker as his partner. While hanging on the wall, he was drawn to a nearby crack system, an old aid route called Tenaya’s Terror (VI 5.9 A4, Bosque-Corbett, 1985). Sean was quick to check it out. The upper 800 feet of the route followed a continuous crack system, flowing from stemming corners to long sections of offwidth, all capped by two steep and difficult pitches to the summit. Below this were two crux pitches and 1,000 feet of beautiful cracks and slabs running downward to the valley floor. Sean spent most of that summer in Tuolumne Meadows, and for training he would run to the summit of Watkins, rappel the upper 800 feet of the wall on a fixed rope, and climb out with a Mini Traxion. By the end of the summer he had freed the upper section and was convinced that if he could climb the crux pitch the rest would go free.

Sean called in the fall, “Hey, Jimmy, you should come check out this free route I’ve been working on Mt. Watkins.” It was all I needed to hear. I packed my bags and raced down to Yosemite. The mission began the same way as most of our trips—out of Sean’s famous doublewide trailer in El Portal. “The Trailer” was a well-known hang for many of the world’s best climbers, regularly teaming up with Sean to storm the castles and make climbing history. Once both of us were over-caffeinated and frantically pacing around at hurricane force, we blew up to the Valley. We spent two days climbing on the wall. I was floored—amazing splitter cracks that just kept going on and on.

Sean called in the fall, “Hey, Jimmy, you should come check out this free route I’ve been working on Mt. Watkins.” It was all I needed to hear. I packed my bags and raced down to Yosemite. The mission began the same way as most of our trips—out of Sean’s famous doublewide trailer in El Portal. “The Trailer” was a well-known hang for many of the world’s best climbers, regularly teaming up with Sean to storm the castles and make climbing history. Once both of us were over-caffeinated and frantically pacing around at hurricane force, we blew up to the Valley. We spent two days climbing on the wall. I was floored—amazing splitter cracks that just kept going on and on.

In April 2013, Sean and I hiked to the base and started working out the free line on the lower half of the wall, starting on an aid route called the Prism (VI 5.10 A3+, Franosch-Plunkett, 1992) to gain Tenaya’s Terror. The climbing was fantastic. But more memorable for me were the fun times camping next to the river, eating gourmet steak burritos, and washing it down with “Jack O’Max”—that’s Jack Daniels and Cytomax. Your head might hurt a little the next day, but your muscles will feel great.

Once the road to Tuolumne Meadows opened we refocused on the upper half of the wall and the crux of the route. We spent about 20 days together on the wall, figuring out the climbing and protection for the endless 5.12 pitches and mid-5.13 cruxes. We were getting real close and looking forward to completing it the next season.

Once the road to Tuolumne Meadows opened we refocused on the upper half of the wall and the crux of the route. We spent about 20 days together on the wall, figuring out the climbing and protection for the endless 5.12 pitches and mid-5.13 cruxes. We were getting real close and looking forward to completing it the next season.

In March 2014 I got a call that Sean was missing in Zion. I wasn’t totally surprised. He had been pushing hard on wingsuit BASE jumping, opening many new jumps and quickly becoming one of North America’s best flyers.

Sean had only started flying after the love of his life, Roberta Nunez, an amazing Brazilian climber, died in his arms after a horrible car accident. Flying though the air was the only thing that brought a smile back to his face and gave him the inspiration to keep living. In time, he’d planted other seeds, finding true love again with a beautiful woman named Annamieka, who was pregnant with their baby boy, Finn Stanley Leary. In so many ways, Sean was like a peregrine falcon, screaming across or up the wall at unimaginable speed—you might catch a glimpse of him just long enough to be in awe at the ability and skill…and then he’s gone! And now he was gone. Flying had at first saved Sean but it ultimately took him; his body was discovered below a cliff in Zion.

While trying to process the loss of my best friend and climbing partner, my resolve to complete our Watkins route only grew. I was nervous because I now wanted to climb the route for both Sean and myself. I hoped I could focus my emotions enough to climb right at my limit and not let us both down.

Fortunately, my good friend Seth Carter had the ability, time, and psych to help me complete Sean’s vision. Starting in late spring, Seth and I spent six days working on the upper half of the route and began stocking supplies for camping on the wall for a later push in June. Of course, we continued the tradition of challenging climbing by day followed by fun nights of camping on the summit.

On June 24 we hiked up beautiful Tenaya Canyon to the base of the wall. We began climbing early the next day. The forecast was for mostly clear skies, but it was hot and the route faces south. We planned to climb in the early morning or late afternoon to avoid direct sun. We hoped we had enough water.

The route begins on a low-angle sea of smooth, blank granite. A wandering slab pitch and the thin corner pitch that follows are a very calf-pumping way to begin the day. From there the route steepens into three 5.12 pitches—a wild chimney squeeze-slot, exposed changing corners, and a delicate layback. Seth had never been on these pitches, and he managed to climb them all onsight. We were moving well. From there the only two easy pitches of the route took us to the palatial Sheraton Watkins ledge and our first bivy.

The route begins on a low-angle sea of smooth, blank granite. A wandering slab pitch and the thin corner pitch that follows are a very calf-pumping way to begin the day. From there the route steepens into three 5.12 pitches—a wild chimney squeeze-slot, exposed changing corners, and a delicate layback. Seth had never been on these pitches, and he managed to climb them all onsight. We were moving well. From there the only two easy pitches of the route took us to the palatial Sheraton Watkins ledge and our first bivy.

The unforecasted rain began slowly that night with the faint pitter-patter that forces you to crawl deeper inside your sleeping bag, hoping it will simply fade away. This time it grew into a torrential downpour and then into a waterfall. We scrambled throughout the night to stay dry under a tarp that I had strung up on the side of the huge ledge. As the rain continued into the next day it was obvious that we weren’t going anywhere. There was no more water problem, but reluctantly we had to ration our food for the unplanned rest day.

The next morning the sun dawned bright and began drying the rock above. We set off again, with a nice 5.11 corner off the ledge leading to the Golden Eagle Pitch. While on the wall we would often see a golden eagle circling around us. I hoped it was Sean with fresh new wings, keeping an eye on us and ripping through the sky like never before. The Golden Eagle Pitch climbs an amazing, gold-colored, left-arching feature for what seems like eternity. The thin, 5.12 liebacking with small gear on this lead is characteristic of the next 500 feet of hard climbing before reaching the crux. The majority of this route is just under vertical and the feet are relentlessly small. It’s one serious leg pump.

That afternoon we arrived on a small ledge two pitches below the crux and set up our portaledge. We spent the next three days resting under our shade tarp until late afternoon, waiting for the sun to move off the wall and allow us to attempt the two thin, technical pitches of climbing above.

The crux pitch is a beautifully featured traverse that, with the exact sequence and perfectly placed feet, just barely allows passage. Sean and I spent a lot of time working on this 5.13b pitch, not sure if we could free climb these powerful yet delicate moves. It was the missing link between the lower and upper crack systems that made this route possible. This leads into a short section shared with the South Face Route—which happens to be the 5.13 crux of that climb. This crux is truly height-dependent; I watched Sean, who was 6 feet 1 inch, hike it many times with ease. For me it’s an all-points-off sideways dyno, usually followed by some expletives. Tommy Caldwell, who is about my height, called this pitch 5.13c, so at least one my heroes thinks it’s hard.

It took Seth and me two afternoons and many falls just to redpoint these crux pitches. We had been on the wall for five days now, and food and water were at a low.

It took Seth and me two afternoons and many falls just to redpoint these crux pitches. We had been on the wall for five days now, and food and water were at a low.

On the sixth morning we blasted off early and headed for the summit. The 5.11 climbing, which continues for three pitches above the crux leads, felt relatively easy and refreshingly fast-moving. However, the final two pitches—5.12+ and 5.12—serve as an effective guard to the summit. The first lead follows an overhanging and leaning crack capped by a powerful, bouldery finish. Without relenting, the final pitch climbs a tricky face to a wildly exposed arête and glorious handjams leading right to the summit.

Once on top, I stood there smiling with tears in my eyes—the end of a bittersweet journey. I had completed my most challenging and meaningful climb to date. But more importantly I had realized Sean’s vision and planted the first seed in my Soul Garden.

Summary: The first ascent of Soul Garden (VI 5.13b) on the south face of Mt. Watkins, June 24–July 1, 2014, established by Seth Carter, Jimmy Haden, and Sean “Stanley” Leary (1975–2014). The 19-pitch route contains two pitches of 5.13 and nine of 5.12. The route starts on the Prism and shares two pitches with the South Face Route; however, it mostly follows Tenaya’s Terror and new free variations to that route.

About the Author: Jimmy Haden lives in Lake Tahoe, California. He has climbed in the wild mountains of Patagonia, Alaska, and Madagascar, but he feels luckiest to have abundant new routes to climb on the beautiful granite walls of the Sierra Nevada.