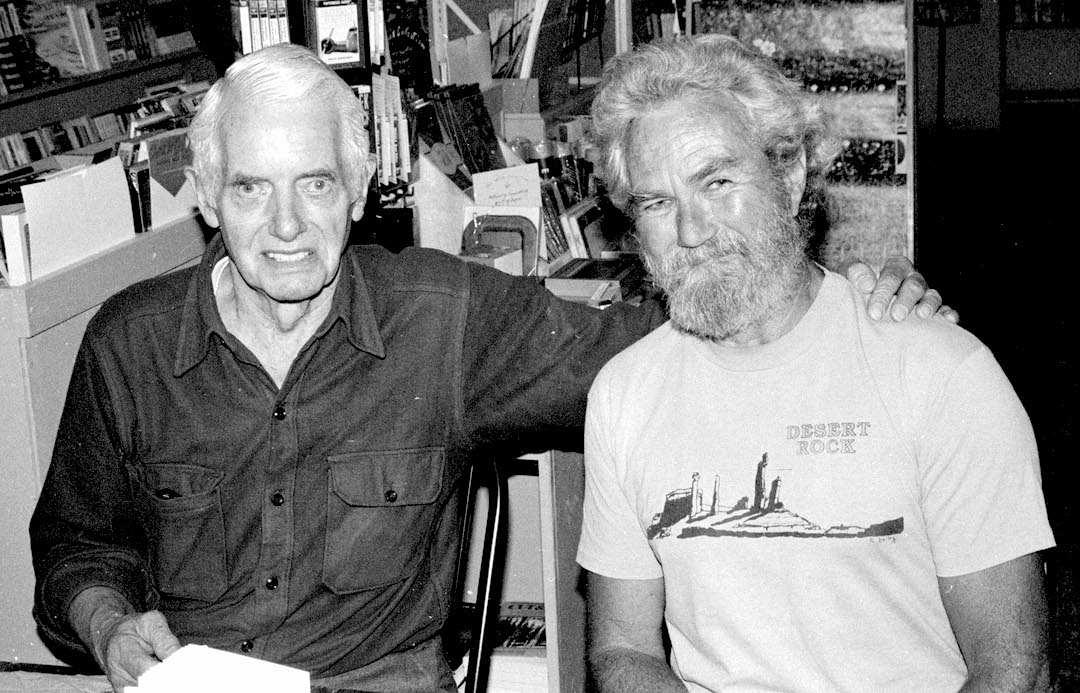

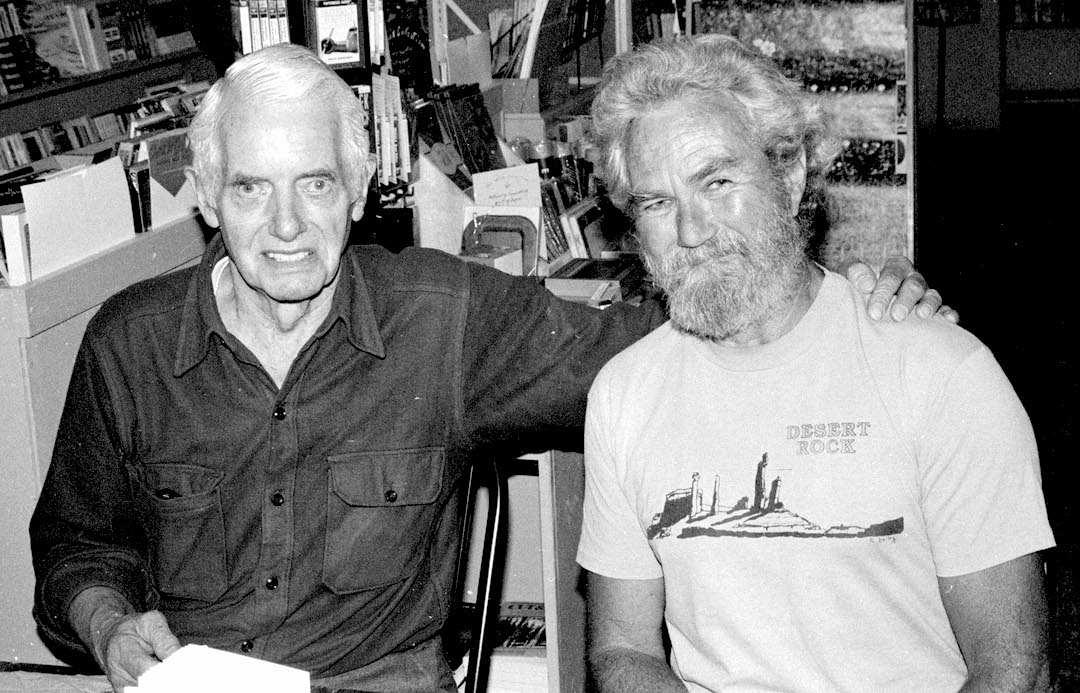

Eric Bjornstad, 1934–2014

Once the realization is accepted that even between the closest human beings infinite distances continue, a wonderful living side by side can grow, if they succeed in loving the distance between them which makes it possible for each to see the other whole against the sky.

— Rainer Maria Rilke

Eric Bjornstad, the greatest chronicler of climbing in the Colorado Plateau area of the American Southwest and a pioneer of significant climbs from Mexico to Alaska, passed away on December 17, 2014, at age 80.

Eric was born October 23, 1934, in Phoenix. His father was a roughneck in the California oilfields, and after years of hard work scraped together enough money to buy a filling station in San Fernando, where Eric and his mother joined him in the late 1930s.

A strong and athletic kid (although he admitted that his blond curls made him look a bit like Shirley Temple), Eric was soon climbing various pieces of equipment and other parts of the filling station, including a thick manila rope that hung from the rafters. In 1940 the family moved to the San Gabriel Mountains, and his father took a job at Pacoima Dam. Here, Eric started hiking when his father went to inspect the dam—undoubtedly the beginning of a love of the outdoors.

As World War II progressed and his father moved to Hawaii to work in the war effort, Eric and his mother went to live with his grandparents in Glendale (Eric’s mother would later join her husband in Hawaii). With his grandparents, he was exposed to music, literature, poetry, history, and storytelling, things that would become a cornerstone of Eric’s existence. Later, the Bjornstads would move to Long Beach, where Eric got heavily involved with the Scouts.

Eric struggled academically, and though he eventually graduated from Toll Junior High School in Glendale, he wrote in his unfinished autobiography that it was “the only school I ever graduated from.” By the time he left school, Eric had had at least a half dozen jobs, everything from shining shoes to ushering at a movie theater to tree topping. In the mid-1950s he moved to Lone Pine to work on the railroads, laying ties (“gandy dancing” as it’s known).

Eventually, Eric made his way to Berkeley, where he was introduced to spelunking. He became friends with the noted physical anthropologist Grover Krantz, and together they explored caves for bones and other relics. They spent considerable time in Samwel Cave near Mt. Shasta.

The 1950s was a period of continued cultural development for Eric. He attended performances at the War Memorial Opera House in San Francisco and Sunday afternoon harpsichord concerts at the Palace of Legion of Honor above Golden Gate Park.

“I also frequented the Bohemian haunts of San Francisco’s upper Grant Street in North Beach, the Co-Existent Bagel Shop, City Lights book store, Ferlinghetti and Kerouac talks, parties and late-night jazz sessions,” he wrote. “It was a time when my feelings and experiences led to my writing volumes of poetry, but the lack of physical challenges and the dissipation of the bohemian lifestyle were taking its toll.” In short, Eric wanted to get outside.

In the late 1950s, the Yosemite scene was still nearly completely unknown to outsiders. The publications about the outdoors that Eric saw often featured activities in the Pacific Northwest, and so he planned a move to Seattle. After an April 1959 going-away party, “…I packed my rucksack with a change of clothes, four choice smoking pipes, my journals, Walden and the two paperbound volumes of The Journals of Andre Gidé. I then distributed my remaining worldly possessions to my good friends.

Giving away all his worldly belongings was one of Eric’s most enduring characteristics. During 1960–’61, he let a penniless Ed Cooper live in his basement while Cooper explored some of his first black and white enlarging and printing techniques. Later, as many who visited him in Moab would recall, he’d often hand them an old book or historical trinket on their way out the door. (In 1992 he gave this writer set of aluminum bongs used when Eric and Ken Wyrick rigged for the filming of The Eiger Sanction in Monument Valley.)

Eric arrived in Seattle’s University District with 26 cents in his pocket. He was soon working as a tree topper again, but had to wait until his first paycheck before he could acquire lodging and decent meals. Meanwhile, he subsisted on soup—ketchup and hot water. He soon jumped the tree business ship and became a cook at a restaurant called Pizza Haven. Days and nights in the university district were spent talking philosophy, poetry, and the arts with academics and bohemians. Eric didn’t meet any cavers—but there were climbers about. Lots of climbers.

Early Days on the Rope

Early in his Seattle days, Eric met Reid Neufer, who studied oceanography and philosophy and was an outdoor enthusiast. Neufer invited Eric on a hike of 5,835-foot Mt. Roosevelt in the Cascades. Additional hikes and even modest roped climbs followed, and Neufer joked that one day Eric’s name would appear in summit registers alongside Fred Beckey’s and Ed Cooper’s—two of Settle’s best-known climbers, who were mentioned in area newspapers on a weekly basis for their activities. Neufer proved to be prescient.

A few weeks later, Eric met a student named David Hiser, and they began roped climbing together. Over the course of many weekends, the two chalked up an impressive list of climbs. Not long after meeting Hiser, and switching jobs again, Eric met Don Claunch.

“From the day I met Don,” Eric wrote, “I embarked upon a blitzkrieg of mountaineering. The days I was grounded to work life, I jogged, traversed brick buildings, mantel-shelved window sills, stemmed doorways, ticked off dozens of one-legged squats, ascended and descended two- and three-at-a-time stairs, and practiced two-finger chin-ups on half-inch door jams, and as I read newspapers each page was crumpled up in the fist to increase finger strength. A favorite test of strength was to hold a bathroom scale at arm’s distance and squeeze to see how high a number could be reached. During the peak of my 1960s climbing days I was always able to squeeze the scales beyond their scale limit, often above 300 pounds. Egocentric as I was, I tested fellow climbers and always outdistanced them. I now reflect that it probably was not my superior strength but perhaps a better technique I used.”

The friendship and climbing with Claunch seemed to become a springboard for the next step. One day in summer 1960, while hanging around the Seattle REI store, Eric found a note written by Ed Cooper, who was looking for someone to share expenses and driving to the Bugaboos. This was the famous summer of Vulgarian madness in the Tetons, during which most of the best climbers from Yosemite, the Gunks, and Boulder met and shared stories and climbs (as well as the Vulgarifone, a speaker mounted to the roof of a Vulgarian’s car, with which they could harass people at the camp with monkey sounds). Cooper was going to the Bugs to meet Art Gran (a Gunks Vulgarian who’d just climbed the north face of the Grand with a hobbled Layton Kor), but decided bringing Eric along would be worthwhile.

There, Cooper taught Eric many of the ideals of climbing and how different styles, techniques, and personal preferences generally dictated how climbs were done. Cooper also put Eric through the paces of bouldering, then easy alpine climbing, then a major new route.

Eric soloed Eastpost Spire while Cooper dealt with a stomach bug, but once he was better, the two made the first ascent of Howser Peak’s north face.

“[Eric’s] enthusiasm was catching, it matched mine at the time, and he seemed game for anything,” Cooper recently wrote. “He did accompany me to the Bugaboos where we did a few modest climbs, but the thing I remember was that he had to get back to work. He walked all the way back to the main highway and hitched a ride all the way back to Seattle. Now that was dedication. I also was surprised to learn of his love for classical music, which, as far as I know, was not shared by any other climbing companion I had in those years.”

While Eric was still at the Pizza Haven, “it quickly became a meeting point for the few dedicated climbers active in the Pacific Northwest at the time,” Cooper noted. “Many a climb was arranged here, and pizzas were mysteriously supplied to us by Eric, as ‘unpicked-up orders’.”

Eric soon switched jobs again and began working as a sort of overseer of various animals at the university’s labs, which he could easily assign to others if he needed a climbing fix.

“As I continued to tick off first ascents and classic climbs in the Cascades with Cooper, Claunch, and Hiser, I began to hound Don to introduce me to Fred Beckey, with whom I knew he had shaken hands on dozens of first ascent[s],” Eric later wrote. “I was thus quite excited when he invited me to a Seattle Mountaineers Club meeting, saying Fred Beckey would probably be attending it as well. While the assemblage of enthusiasts milled about after the traditional slide presentation, Don took me over to Mr. Beckey, who was standing in a circle of admirers. We were introduced, and as we shook hands he acknowledged having heard of a couple of ‘interesting’ climbs I had done with Ed; then he abruptly turned and continued his conversation with his companions. His response was a disappointment. I had hoped to be able to discuss mountaineering adventures with him, of course making reference to some of my better climbs, and, as a result, maybe plan a climb together. I was amused to learn later that almost any oaf, were he (not she, at the time) able to demonstrate ability for high standard climbing, would be acceptable as a partner. Little attention, on the other hand, was given to his social graces. Nonetheless, that night, as I left the meeting, I had quite a bright glow on my face and in my heart from having shaken hands with the great mountain man.”

Eric was soon teaming up with Beckey on whatever Beckey thought they should climb. Although Eric would later say that 90 percent of his climbs were done with Beckey, and only 20 percent of Beckey’s climbs were done with Eric, the two forged a bond that would never be broken (even after some of their massive—and colorful—fall-outs).

Within just a year, Eric had become arguably one of the best climbers in the Pacific Northwest, and by the end of the summer of 1961, was climbing almost exclusively with Cooper and Beckey. “I’d climb half a week with Ed and half a week with Fred,” he said in a 2010 interview, noting that Cooper and Beckey had had some kind of falling out. “Then I opened the coffeehouse and that allowed me to climb every day… If I wanted to get away to climb, I’d just leave the place in charge of my best help, oftentimes a waitress that had worked for me for [just] ten days. ”

During the 1960s, with Seattle’s best (Beckey, Cooper, Claunch, Dan Davis, Mark Fielding, Alex Bertulis, Dave Beckstead, Don Liska, Leif Patterson, Pat Callis, Art Davidson, Steve Marts, Curtis Stout, and others), Eric established dozens of new climbs at all grades and all sizes, from the local crags to Alaskan peaks, his best known climbs including the first ascent of the northeast buttress on Mt. Slesse (1963) and the first ascent of Mt. Seattle (1966).

Despite his climbing record, Eric often suggested that driving the Al-Can highway three times was as great an achievement.

Desert Rock

Eric’s first trip to the desert Southwest was, not surprisingly, with Beckey. Their goal was the “South Buttress” (now often called the Beckey Buttress) on Shiprock in 1965. Eric brought along his very tattooed girlfriend, Christa, which didn’t sit well with Beckey, and after 1,000 feet of progress Eric and Christa left. As Eric and Christa hitchhiked back to Seattle, Beckey followed them in his pink Thunderbird, taunting them every few hours but not offering them a ride; the taunting lasted to Oregon. Eric later called the event comical, and Beckey recruited Alex Bertulis, then Harvey Carter, to complete the route. Eric and Beckey went on to first ascents of Echo tower (1966), the third route climbed in the Fishers, as well as Middle Sister (1967) in Monument Valley.

In 1965, Eric began staying in Moab for long stretches with local rock-shop owner Lin Ottinger, as well as driving for Ottinger’s guided desert tours. In 1970, Ottinger invited Eric and Beckey to fly over Canyonlands to look at a tower Ottinger had found during one of his hundreds of trips through the desert. Ottinger knew a pilot at the Moab airport and he talked him into a swing over Taylor Canyon, where Eric and Beckey were introduced to Moses tower.

“It was pretty spectacular,” Eric said. “Problem was we only had a couple of days to climb it.”

During the first visit, Eric climbed Zeus (Beckey stayed on the ground) and hatched plans to return in 1971. That didn’t work out, but in 1972 they returned with Tom Nephew, Jim Galvin, and Gregory Markov. Eric suggested a route up the west face, which they attempted, but a loose block turned them back and they turned their attention to the north face. Five days and two bivouacs later, on Eric’s 36th birthday, they reached the summit. It was arguably the last major tower to be climbed in the Moab area.

During the early 1970s Eric made his biggest impact on desert climbing with a string of first ascents of notable towers, including Eagle Rock Spire (1970), Zeus (1970), the Bride (1971), Disappearing Angel (1971), Chinle Spire (1972), Jacob’s Ladder (1973), Bootleg Tower (1974), and Sewing Machine Needle (1975). He also climbed the first route in Valley of the Gods, North Tower, in 1974, and the first two pitches of Artist’s Tears (with Jimmy Dunn), a thin seam up a slightly overhanging wall on River Road that would point the way to very difficult artificial routes in the Fishers and Zion in subsequent decades.

After a decade of trips to the Moab area, Eric finally moved there full-time in 1985. During the previous decade, he had helped complete a 10-year air-quality study with Harvard University, and it was time for a change. “They paid me so much money I couldn’t quit,” he said. “And I only worked eight months out of the year…. I coordinated one of three field teams investigating the effects of air pollution on lung health. Great job because I was independent, I was my own boss.”

The Desert Rock guidebook (1988) was Eric’s idea, but he figured Beckey would write it. However, Beckey was too tied up with other projects, so Eric started plowing away. It was a monstrous project, and Eric wrote thousands and thousands of letters to climbers all over the world. The perennial inclusionist, Eric asked a variety of climbers (Kyle Copeland, Don Liska, David Brower, Huntley Ingalls, Layton Kor, Bill Forrest, Ernie Anderson, Bestor Robinson, and others) to write sections of the book. He gathered hundreds of images and carefully matched climbers’ pictures to areas of the desert where they’d left their marks. At one point he told this writer me he’d put 10,000 hours into Desert Rock, and that figure was likely conservative. George Meyers’ Chockstone Press gave him $3,000 as an advance, but money had nothing to do with it. The result was what many have regarded as the finest climbing guidebook produced in the United States up to that time.

“Obviously the (for the time) complete nature of the book’s coverage kept it relevant well past the printing,” noted George Meyers recently. “The slow sales were not atypical of lots of climbing guides. In this case, obscure route descriptions were virtuous. The trick was to print a long enough run to get the costs down but not so many that a book was hopelessly out of date. With the desert, aside from Indian Creek, it was never a real destination for the hordes that would necessitate constant updating of the guide. Typically of the many guides we published, I merely steered the formatting and presentation and let him run with the material as he knew it.”

The growth in desert climbing after Desert Rock was exponential, and by 1994, Chockstone had signed Eric up to write a series of books covering desert climbing. The four volumes were released between 1996 and 2003, and again Eric pulled in whomever he could to help, notably the late Mike Baker, Jeff Widen, Beckey, and a few others.

Slowing down and with various ailments, including sciatica, Eric’s last significant climbs on desert rock would be in the mid-1980s—things like Rhino Horn, the Scorpion, and Zenyatta Entrada.

“Eric also had a dark side which did not serve him well in his later years, and that is his relationship with women,” Cooper recently wrote. “I was a witness to some of this. Without elaborating, his later years would have been more enjoyable were this not the case.”

Indeed, Eric married at least three times and had at least five children, most of whom didn’t meet their father until they were grown—Eric rarely sought them out. In the mid-1990s, one of Eric’s children, Mara, moved to Moab for a year to get to know her father. She quickly learned that Eric’s first love was climbing; his second was women, and not necessarily women he knew. His fondness for wine didn’t help the situation. In fact, Eric’s closest friends and family members often found it difficult to sort out fact from idea—sorting out and understanding Eric’s personal life will, I predict, not be complete for many years.

Eric the Great (Intellectual)

I’ve read in recent posts of people suggesting Eric Bjornstad was a “desert rat” and a “climbing bum,” both of which are colorful descriptions, but Eric was much more. His knowledge and appreciation of the arts, literature, desert ecology, desert flora and fauna, desert soils, desert history, Native American beliefs and traditions, poetry, trails, geology, music, philosophy, glassmaking, and woodworking were beyond just pedestrian understanding of these subjects. (Who else would have a Marcel Proust quote next to an Yvon Chouinard quote in a guidebook to desert climbing?)

I remember a heated discussion about climbing styles one day in the mid-1990s, and Jimmy Dunn came running in Eric’s door. “Eric, Eric. Come look at this cool spider I found.” Everything was dropped as we went to look at Dunn’s spider. Climbing arguments be damned; the greater world—the natural world—called.

Despite great shyness, Eric was also a teacher of sorts. Any book you wanted to borrow, any part of the natural world you wanted explained, any information about poetry, literature, and music you needed, Eric would offer it up, along with encouragement to learn more on the subject. Even better were his personalized and private tours of his favorite places in the desert.

In 1993, he took my wife, Ann, and me, John Middendorf, and Luke Laeser on a tour of Arches’ Fiery Furnace, even though we’d all been through it a few times already—Eric was that excited about the natural world, especially the natural world around Moab.

Many climbers who remember Eric from his later years in Moab, collecting information on climbs and pulling together guides to the desert, might remember an aging man with a number of physical handicaps. It was hard to see the young tiger Eric had once been. (He was leading 5.9 by 1961). But his mind was unstoppable, constantly churning through information—people, places, and events—and relating them back to the greater whole, to their places in history and personal trajectories. Eric had knowledge, experience, and keen sensibilities beyond most climbers you will ever know. And thankfully, for all of us, he used them wisely.

Presciently, Eric wrote in his unfinished autobiography, “The happenings one remembers will always be selective and imperfect and differ from what was actually experienced, and writing about them will even further distort what in fact took place. For we are a different person than we were when the happening we are remembering and writing about took place.”

Anaïs Nin reminds us, “We don’t see things as they are, we see them as we are.”

Eric is survived by his five children: David, Neith, Eiger, Heather, and Mara Bjornstad; seven grandchildren: Ryan, Auna Laisa, Aaron, Clara, Francis, Melina, and Tikaeni; and one great grandchild, Liam. He is missed dearly by family and friends, and by thousands of climbers from around the globe.

—Cameron Burns, with contributions from Mara Bjornstad, Ed Cooper, and Todd Gordon