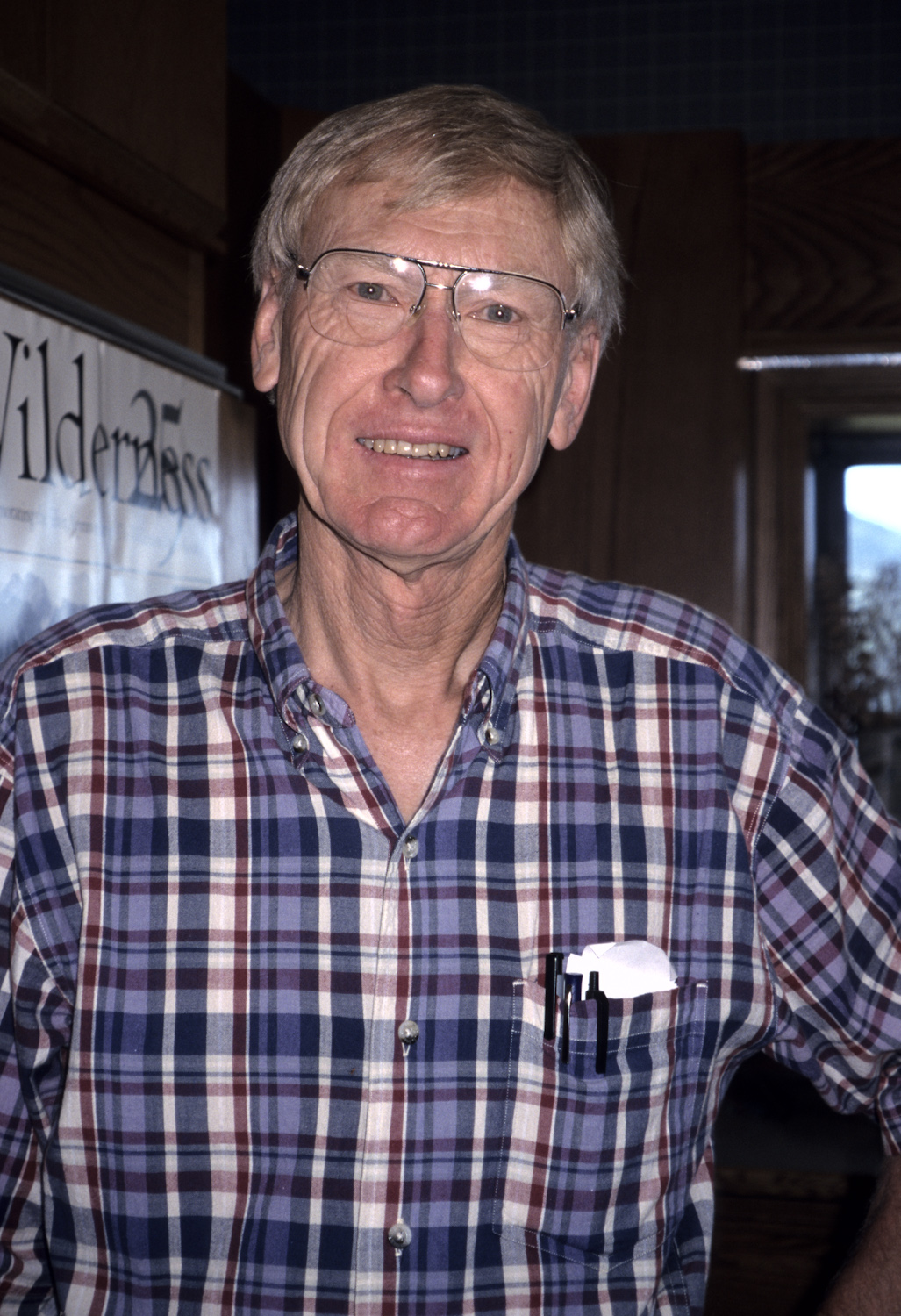

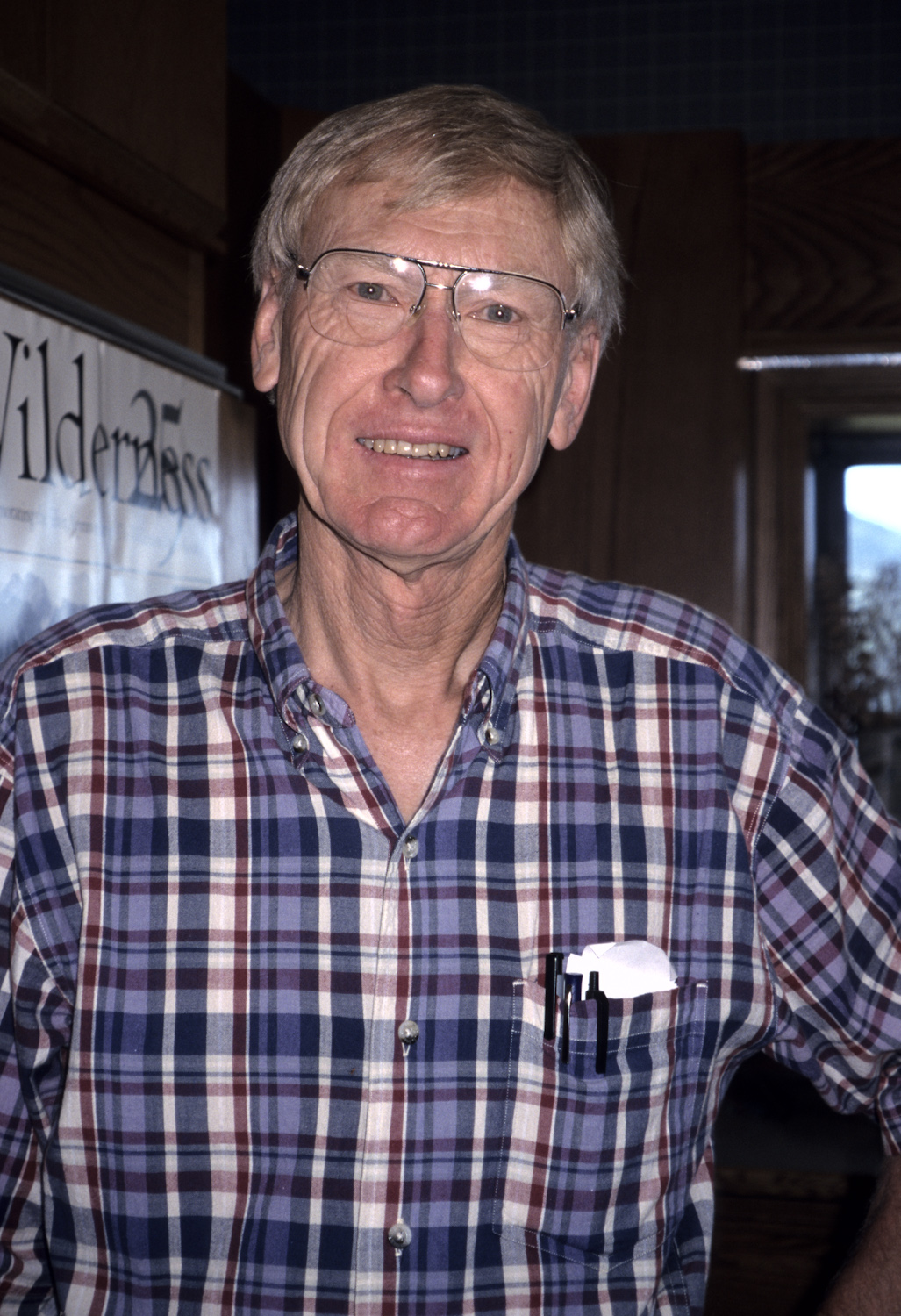

Dale Johnson, 1931-2012

In the introduction to his autobiography, Dale Johnson quoted Christopher Morley: “There is only one success: To be able to spend your life in your own way.” This philosophy was a cornerstone of Dale’s approach to life, guiding the roles he played not only in the mountains, but also in business.

In the introduction to his autobiography, Dale Johnson quoted Christopher Morley: “There is only one success: To be able to spend your life in your own way.” This philosophy was a cornerstone of Dale’s approach to life, guiding the roles he played not only in the mountains, but also in business.

From his earliest years as a climber, Dale was a leader. As Pat Ament put it in his book on the history of rock climbing in Colorado, the young

Boulderite “would help bring Colorado climbing into the modern age.” One of Dale’s first ascents was the Northwest Overhang of the Maiden in Boulder’s Flatirons in 1953. On the Maiden, his aid technique involved a bolt, a pin and, in his words, some “calculated risk,” in which he ultimately decided the possibility of falling would be worth the gamble. When the pin pulled, he fell and…nothing happened. The gamble had paid off. Such acceptance of falling was unprecedented at the time. Ament called it the “first recorded event of its kind in Colorado climbing.”

Dale continued his string of first ascents with the south face of the Matron and the Redguard route in Eldorado Canyon. His second ascent of Shiprock in New Mexico was perhaps even more coveted. In 1957, he added the Jackson-Johnson route on Hallett Peak to his list of ascents. In 1952 he spent a summer based in Chamonix, and climbed Mont Blanc, the Matterhorn, Monte Rosa, the Eiger, and the Marmolada in the Italian Dolomites. In 1963 he also organized an expedition to the Peruvian Andes for 40 Colorado Mountain Club members, leading them up two 20,000-foot peaks.

In 1964 he guided Colorado Mountain Club members up Mont Blanc, the Jungfrau, the Matterhorn, the Cima Grande and 14 other peaks in just seven weeks, for $750. He did it not for the money, but because he loved sharing the mountains. The Colorado Mountain Club recognized Dale’s ambition and commitment by presenting him with their highest honor, the Ellingwood Mountain Achievement Award. He also donated money to help build the American Alpine Club headquarters in Golden, Colorado.

In 1958, Dale partnered with Gerry Cunningham to form Gerry Mountain Sports. Dale opened and managed the first retail store in Boulder. The two came together at a time when the outdoor industry as it is known today did not exist. They farmed out sewing for their backpacking and climbing equipment to home-based seamstresses in the Boulder area (large-scale manufacturing of items like tents and sleeping bags wouldn’t begin until years later).

In 1965, Johnson left Gerry to plan his next move, developing the company he would eventually name Frostline Kits. He had envisioned teaching customers to construct their own jackets, tents, and sleeping bags on their home sewing machines. The kits were much more reasonably priced than a ready-made jacket or tent would be, and enabled many outdoor enthusiasts who otherwise wouldn’t have been able to afford traveling and camping in the backcountry to be able to do so. Thirteen years after Frostline’s inception, Dale sold the company to Gillette, the razor blade company. He was 48. From then on, his full-time focus would be on his other projects: wilderness travel and flight. He observed in his later years, “As I’ve grown older, I’ve required more wilderness, not less.”

Throughout his climbing life, many of Dale’s most significant ascents were with his family. His CMC trip to Europe 14 years earlier had included his wife and son. Before the summer was over, Dale had the three of them on top of Switzerland’s Breithorn and Monte Rosa, as well as the Cima Grande and Civetta in Italy. Brad was nine then. It was an achievement that set expectations for many shared summits to follow.

In the ensuing years, he and Brad tagged Kilimanjaro (1969), and revisited Dale’s north face route on Hallet’s Peak (1970), where Dale led all the pitches. In 1972, they climbed the north face of the Grand Teton. By then, Brad was 17 and Dale was 41. They teamed to climb Mt. Kenya in 1974, where they shared leads as equals. It was a climb whose timing found them on a shared rope, and as close to the height of their respective individual powers as they would ever be. Most father-son partnerships never approach a moment of true equality. And true to the Johnson drive, both of them continued excelling, albeit in different directions. At this point, Brad was forging his own climbing career and Dale was immersed in Frostline and flying.

A long 17 years later saw Brad taking Dale up Island Peak in Nepal; the Johnsons also joined forces on the north face of Quitaraju in Peru. Brad had convinced his father to get back on the rope one last time to simul-climb the 700-meter, 55-degree ice face. Dale fielded falling ice at the bergschrund, along with the requisite exhaustion by days’ end – all routine features of alpine climbing. The difference was, he was 64. Now Brad was the lead guide.

Brad later penned a story for Rock & Ice, comparing his life with Dale to Harry Chapin’s song, “Cat’s in the Cradle,” the 1970s anthem about a son and his father swapping roles later in life, and the boy emulating his father. Dale and Brad’s story turned out to be both different from, and similar to, the theme of Chapin’s song. Did Dale view their climbing lives as a Chapin-like changing of the climbing guard? Or was he just glad to be sharing a few transcendent moments with his son, to whom he had shown the summit experience so many years earlier?

Dale Johnson passed away in Boulder on February 23, 2012. Brad was at his side.